Joan Mitchell (1925 – 1992) in her studio, Paris, France, September 1956. Photo: Loomis Dean / The LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock

A Creative Force

“I could certainly never mirror nature. I would more like to paint what it leaves with me.”

Fearless in her experimentation, Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) painted what she wanted to paint. Her abstract canvases grew from recollections of fields and gardens, people she loved and fought with, favorite poems, music, flowers, and even her beloved dogs. In a career that spanned nearly five decades, the Chicago-born artist distilled feelings and memories into her vast canvases without bowing to prevailing schools or styles. She created compositions of unparalleled beauty, strength, and emotional intensity, pushing abstract painting into uncharted territory that she defined.

Co-organized with the Baltimore Museum of Art, Joan Mitchell throws fresh light on Mitchell’s art, from her early paintings in New York and Paris to those from her later years in the French countryside and her ceaseless travels in between. Through more than eighty works, along with photographs and letters, the retrospective reveals an artist of the highest order — one who lived life at an operatic pitch, rarely receiving the type of recognition her monumental work deserves.

Below, take a quick look at eight of Mitchell’s paintings on view in the retrospective, with musings from co-curator Sarah Roberts, SFMOMA’s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Curator and Head of Painting and Sculpture; assistant curator Marin Sarvé-Tarr; and former curatorial assistant Meredith George Van Dyke. See the works in person from September 4, 2021–January 17, 2022 on Floor 5.

1. Making a mark with Lyric (ca. 1951)

“I want to make myself available to myself. The moment I am self-conscious, I cease painting.”

Joan Mitchell, Lyric, ca. 1951; Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York, gift of William Rubin; © Estate of Joan Mitchell; photo: Chip Porter

Raised in Chicago immersed in art, poetry, and music, Mitchell chose painting to be the center of her life at an early age. After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she traveled to France, then settled in New York in 1950, just as the gestural and seemingly spontaneous style now called Abstract Expressionism took hold. She quickly made friends with leading artists and, by 1952, had her first solo exhibition in New York City at the New Gallery, which included this work.

Her paintings at that first show featured pulsing, colorful forms punctuated by angular lines and contrasting colors; Lyric was arguably the most radical. “Measuring just over six feet wide, its dynamic composition creates a centrifugal sense of movement with swirling forms in bright, luminous colors,” says Sarvé-Tarr. “The title references at once the vibrant experience of city life and the artist’s lifelong interest in poetry and music.”

Although she found success in an artist’s circle that included Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, and Franz Kline, Mitchell had grander ambitions. She saw herself as part of a longer arc of art history reaching back to nineteenth-century painters Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and Vincent van Gogh, whose work she studied and aspired to rival.

2. The layers to her City Landscape (1955)

“Man made a city; nature grows. I see it all as nature. I look at it all as what I see.”

Joan Mitchell, City Landscape, 1955; The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Society for Contemporary American Art; © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Mitchell titled several paintings from the 1950s City Landscape, pointing to the lack of distinction she saw between urban and natural environments. “For Mitchell, natural landscapes and cityscapes were deeply intertwined in her experiences of the world,” says Sarvé-Tarr. “She saw them both as ripe territory for painting.”

Made in 1955, this work shows how she deftly orchestrated a vast range of colors, from ragged swipes of hot pink and red with licks of blue, green, ocher, and black. “Look closely when you see the painting — the canvas shows the complex ways she built up layers of marks, dripping lines, and vast swatches of color to create a vibrant interwoven visual space,” Sarvé-Tarr adds. “Cloudy greys and textured whites around the edge of the composition draw the eye to the central tangle of dense, bright gestural marks in an incredible range of colors, revealing her careful approach to painting.”

As Mitchell’s reputation rose, her social circle grew. She traveled frequently to Paris beginning in 1955 and met international artists and writers, beginning a long romance with French painter Jean Paul Riopelle. The scale and complexity of her paintings soared as she folded in these new memories, places, and feelings. It was in this period of experimentation that she made The Bridge (1956), one of her first known diptychs, or a work made up of two panels.

3. Over the Atlantic in To the Harbormaster (1957)

“I wanted to be sure to reach you;

though my ship was on the way it got caught

in some moorings. I am always tying up

and then deciding to depart.”

—Frank O’Hara, To the Harbormaster, 1957

Joan Mitchell, To the Harbormaster, 1957; AKSArt LP; © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Between 1955 and 1959, Mitchell split her time between New York and Paris, where, in the latter city, she felt less pressure to conform to prevailing styles. She sent flurries of postcards and letters to friends during this period, keeping close ties in New York.

This painting, titled after dear friend Frank O’Hara’s poem To the Harbormaster, embodies the vast expanse of water between her two cities. “The poem is very much about longing and loving and loss, and I think those feelings ring true with Mitchell’s life at this moment,” says Roberts. “She was traveling back and forth constantly and was like ships passing in the night with friends who were also always on the move. I’m fascinated by the way this painting is practically split down the middle. You could think of the two halves as having a sense of coming and going.” The complex painting is one of many references Mitchell would make to O’Hara in her work, and books of poetry and letters on view in the retrospective evidence their deep bond.

Mitchell moved to France permanently in 1959 and settled into a studio on rue Frémicourt in Paris. She truly reveled in the material qualities of oil paint in the years that closely followed, squeezing it from tubes directly onto the canvas and scraping, throwing, flicking, and whisking it through the air to land in bewildering webs, threads, shreds, and droplets. In the mid-1960s, Mitchell took up sailing, exploring the Mediterranean and French Riviera with Riopelle, often for weeks at a time. Fresh visuals from her seaside excursions would lead to exquisite works, including Girolata Triptych (1963).

4. Staking a claim in My Landscape II (1967)

“I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me—and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed.”

Joan Mitchell, My Landscape II, 1967; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., gift of Mr. and Mrs. David K. Anderson, Martha Jackson Memorial Collection; © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Mitchell made My Landscape II in her rue Frémicourt studio as she began a search for a country home. Bursting forth in a tangle of greens and bright blues, the work’s mass of painted tendrils call to mind an overgrown houseplant, while its colors evoke the vibrancy of nature unchecked and in full bloom. Mitchell, then in her early forties and painting on her own terms, nearly covered the canvas in a complex array of brushwork.

“Mitchell is famous for her statement ‘I carry my landscapes around with me,’ pointing to the strength of her visual and sensory memories of particular places and views,” says Van Dyke. “My Landscape II embodies that quote more than almost any other work. You can see the way the surface erupts in bubbles of cobalt blues amid a field of lush green and sprays of raspberry and mustard.” Mitchell’s paint tubes, brushes, and even one of many dog food cans she used to mix paint are on view in the galleries, offering a glimpse into the artist’s process.

Soon after she finished My Landscape II, Mitchell bought an impressive estate known as La Tour in Vétheuil. Just northwest of Paris, the small village drew connections to the nineteenth-century French painters she studied, most notably Monet, who had lived and painted in a cottage at La Tour.

“With the painting’s title, Mitchell stakes claim to her land in the city, the studio, and the countryside,” Van Dyke adds. “It is full of color and life.”

5. Luminous passages in Sans neige (1969)

“Well, I live in it. I walk in it. It’s fabulous. The garden, the trees, the church . . . the fields behind where Monet did his ‘Poppy’ things that are in the Louvre, the Seine right below, oh the barges going by, want to come?”

Joan Mitchell, Sans neige, 1969; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, gift of the Hillman Foundation; © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Made shortly after her move to the countryside, Sans neige showcases Mitchell’s full range of mark-making, from luminous passages of wet-on-wet paint and drippy washes to thickly built-up impasto, or paint that adds deep texture and pops from a surface. “This is one of those paintings that will stop you in your tracks,” says Van Dyke. “It is a tour-de-force of color.” The title Sans neige, or “no snow,” could be a sly reference to Monet’s paintings of Vétheuil in winter completed close to a century earlier; Mitchell vacillated in her career between embracing and distancing herself from the artist’s legacy, but here she seemed to court the comparison.

La Tour offered more space to create the formidable multi-panel masterpieces of her later years. “Her move there also offered fresh and stunningly beautiful views: a lake off in the distance, conserved forests hemmed in by country roads, and the winding river Seine,” says Van Dyke. “With Sans Neige, she built up horizontal bands that appear to emerge and recede across the three canvases, suggesting the landscape that surrounded her.”

The retrospective is the first time this triptych has been shown outside of its permanent home at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburg in more than 40 years. “We were lucky that it could travel to San Francisco,” Van Dyke notes. “Some sections of the painting are built up with heavy impasto that could have flaked or resulted in losses if the work had shipped without treatment. Thanks to a team of dedicated conservators, Sans neige was treated, stabilized, and cleared for travel!”

6. From her perspective in Weeds (1976)

“I don’t close my eyes and hope for the best. If I can get into the act of painting, and be free in the act, then I want to know what my brush is doing.”

Joan Mitchell, Weeds, 1976; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn; © Estate of Joan Mitchell; photo: Ian Lefebvre, Art Gallery of Ontario

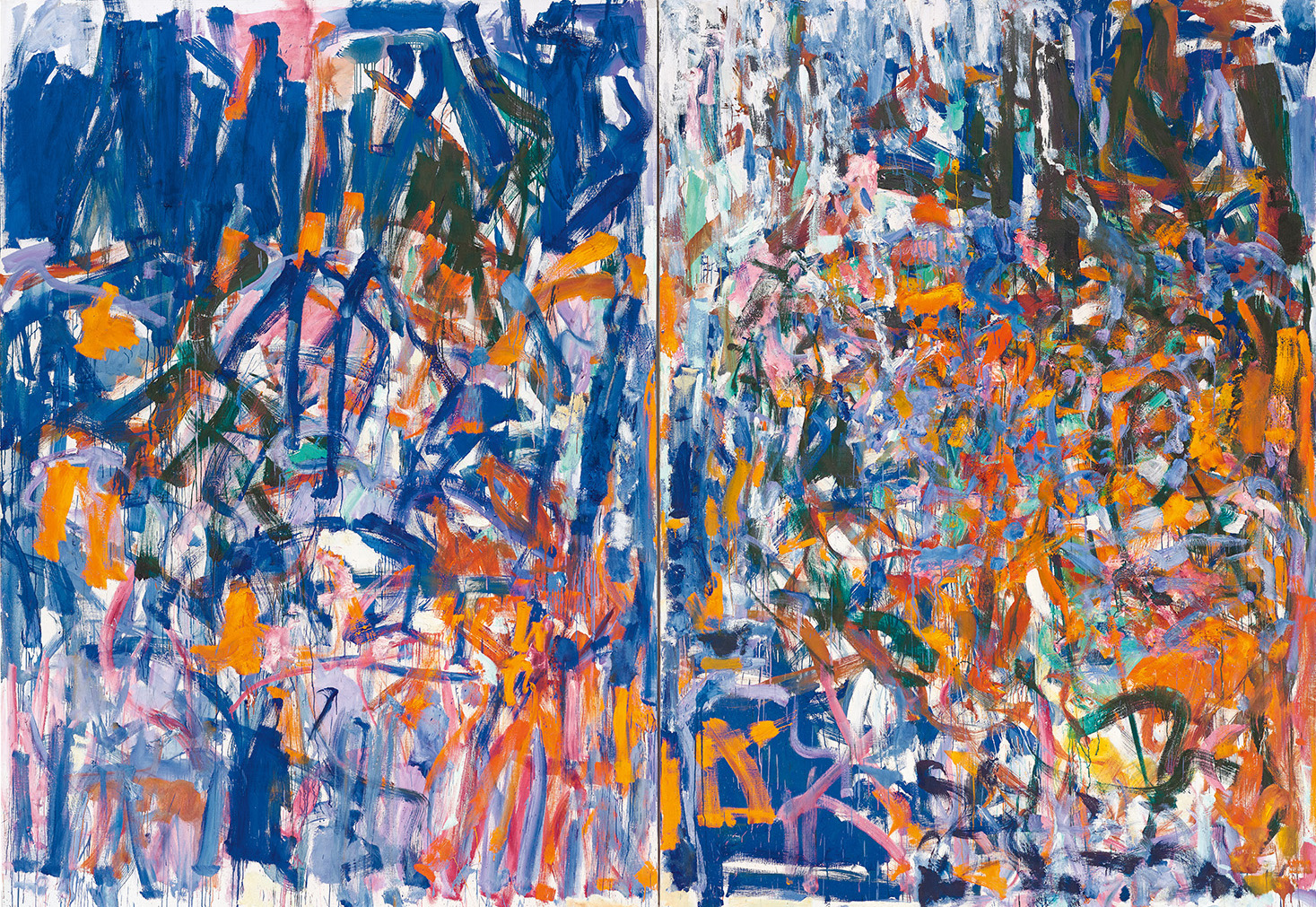

A critic remarked that it was as if Mitchell’s viewpoint had shifted from “observing nature” to “pressing one’s face in it” after the 1976 debut of a series of paintings, including the diptych Weeds. “It’s very up-close, immersive, very sensual — you can really feel this thicket she might be thinking about or looking at closely, as if you are diving into it yourself,” Roberts says.

A master of color, Mitchell limited her palette to complementary shocks of blue and orange and pink and green. Under her careful and controlled brushwork, the colors intensify, sprouting upward and wayward like the unruly flower that inspires them. “There are a few brush marks that actually span the gap between the two panels, but it’s almost as if there are two views, perhaps one a little more pulled back than the other,” says Roberts.

Flowers were deeply important to Mitchell; she had a special affinity for those often perceived to be weedlike. “Mitchell said later in life that she felt like a weed,” Roberts explains. “She saw weeds as persistent and strong and not always appreciated, but beautiful to some.” Roberts and exhibition co-curator Katy Siegel, from the Baltimore Museum of Art, titled the introduction to the exhibition catalogue “Beautiful Weed” in reference to Mitchell’s feeling for the plant. (Their working title for the retrospective, meanwhile, was “Fierce Beauty.”)

7. At heroes’ height in No Birds (1987-88)

“I just got up on that f*cking ladder and told myself, ‘This stroke has to work.'”

Joan Mitchell, No Birds, 1987–88; private collection; © Estate of Joan Mitchell; photo: Kris Graves

Mitchell held onto painting with ferocity in the last decade of her life, despite battling illness, pain, and depression. It was in this period that she truly reckoned with her painting heroes. With No Birds, Mitchell created an extraordinary response to Vincent van Gogh’s painting Wheatfield with Crows (1890). “It’s an act of homage, to be sure, but it’s also a challenge to herself,” Roberts says. “With No Birds, Mitchell offered her work as equal to van Gogh’s.”

Though still abstract, Mitchell’s interpretation doesn’t stray far from a recognizable landscape; the painting’s horizontal structure suggests field and sky, while yellow strokes in the lower center suggest a foreground. Mitchell noted that she valued van Gogh’s intense colors and declarative brushwork, yet with this canvas she emphasized her identification with his deep psychological and emotional connection to the natural world.

“At this point, Mitchell’s thinking about the elements of the painting that matter to her — it’s the color, the intensity, the overall composition,” Roberts says. “She had a consuming determination to continue to paint at the highest level, in spite of it all.”

8. Formidable and majestic in Bracket (1991)

“The solitude that I find in my studio is one of plenitude. I am enough for myself. I live fully there.”

Joan Mitchell, Bracket, 1989; The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; © Estate of Joan Mitchell; photo: Katherine Du Tiel

Completed a few years before Mitchell’s death in 1992, Bracket is imbued with all the gestural vigor and symphonic color that she first deployed in the early 1950s. With surging strokes of cobalt blue, sienna, and emerald punctuated by surprising flashes of pink and chartreuse, the painting manifests a sense of impassioned discovery through color.

Mitchell’s virtuosity and fearlessness with color enliven all the works made in the last decade of her life. She pushed intensity and contrast to the edge of what the eye can take in and incorporated a dizzying array of colors, as if she were determined to make use of every tube and can of paint in her studio.

In 1986, when asked what inspired her to paint while ill, the artist recalled a view she had seen from a window: “I saw two fir trees in a park, and the grey sky, and the beautiful grey rain, and I was so happy. . . If I could see them, I felt I would paint a painting.”