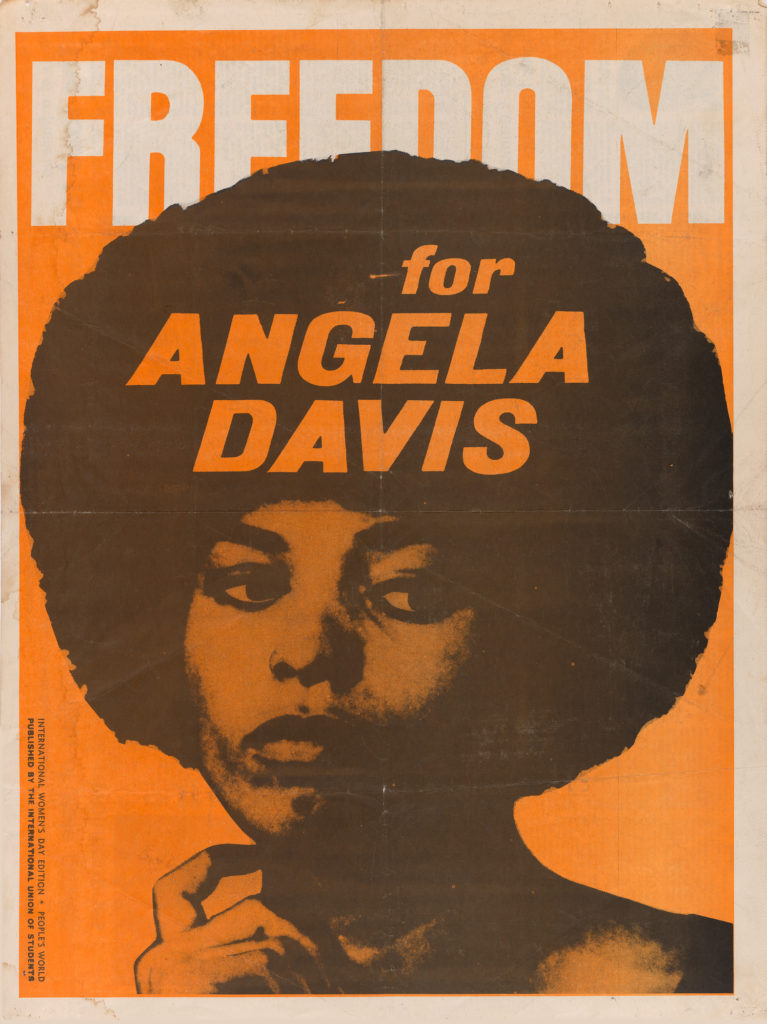

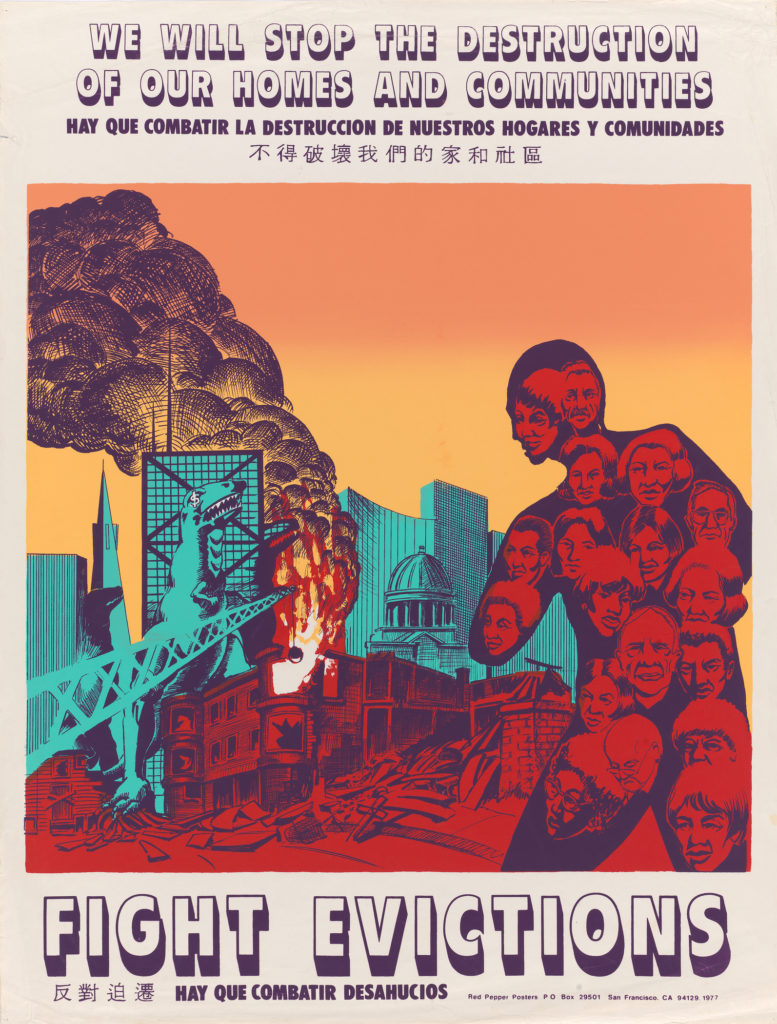

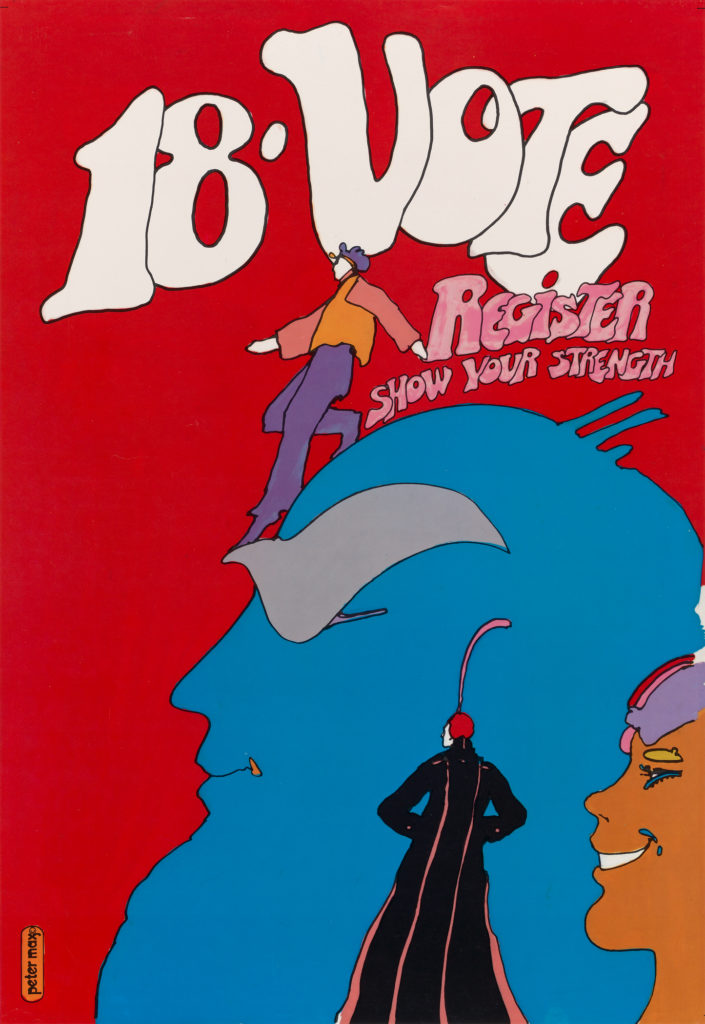

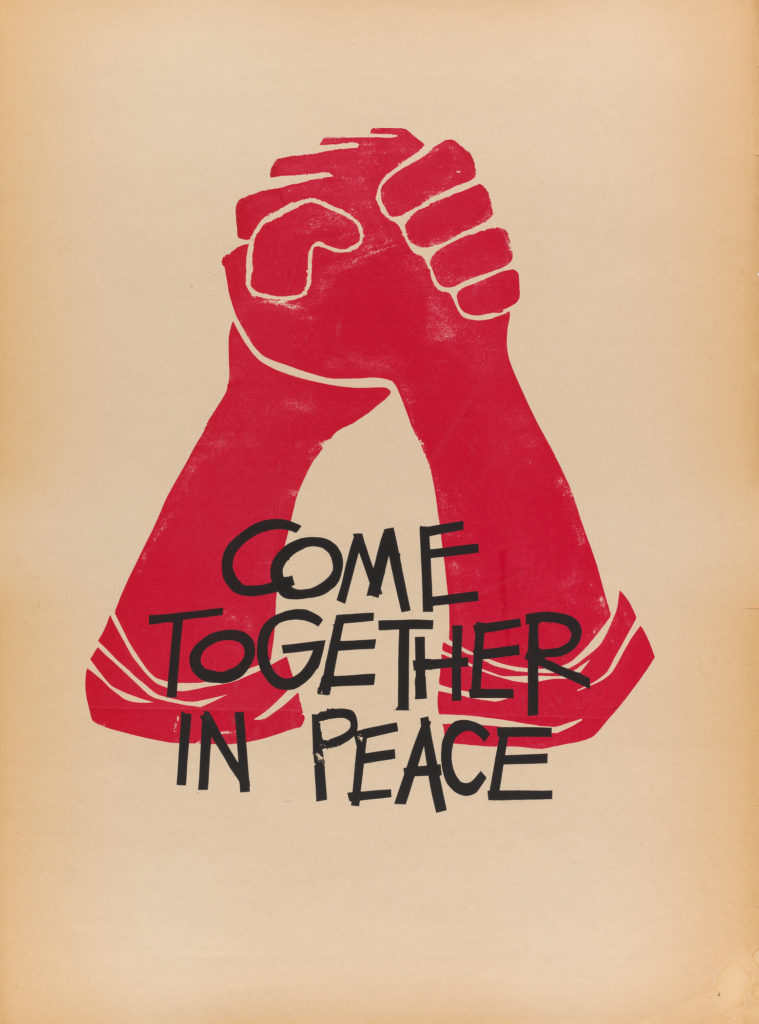

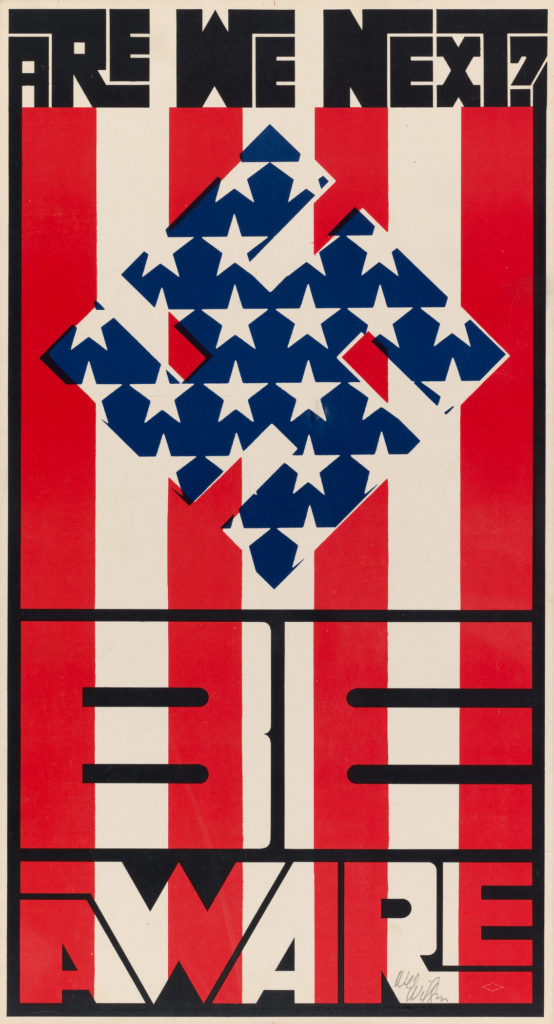

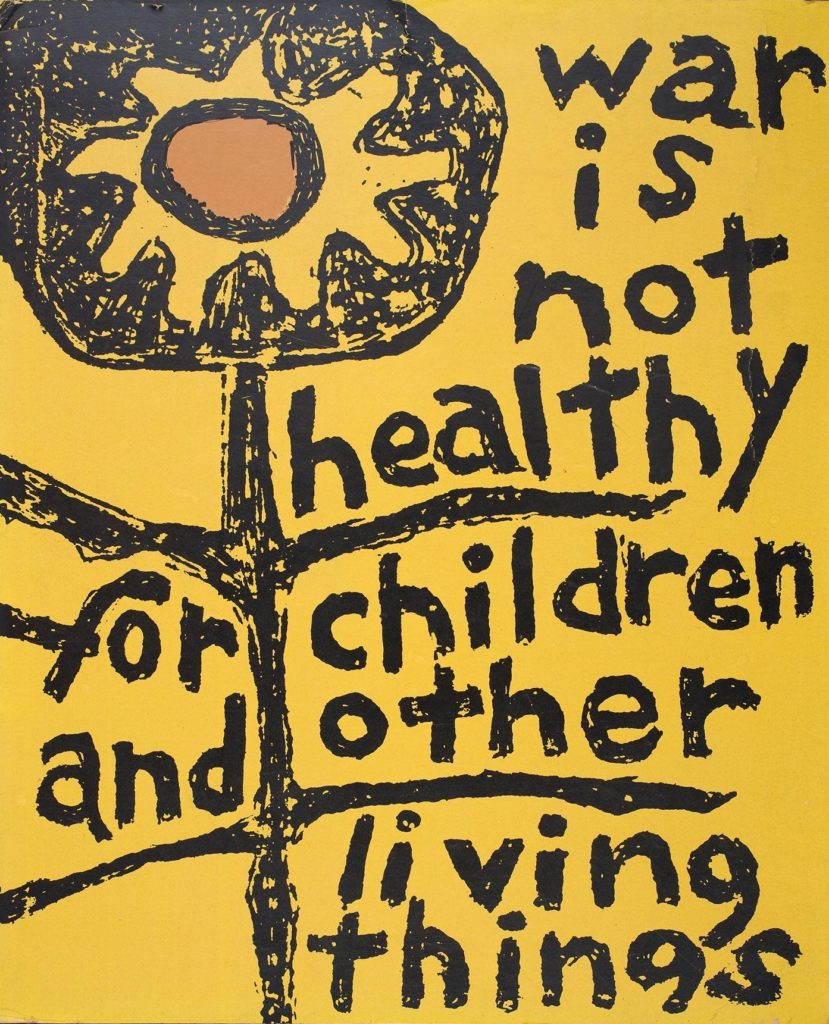

A successful political poster is transformative. At its most effective, it turns image to emblem, onlooker to activist, text to chant. At its most potent, it embeds in the cultural zeitgeist, eventually moving from the outstretched arms of demonstrators to the pages of history books.

At last count, there are nearly 500 political posters in SFMOMA’s collection, a testament to the role graphic design plays in inspiring and informing that type of political action. The assortment includes posters crafted by famous artists and disseminated around the globe, along with anonymous pieces that underscore the Bay Area’s rich history of hyperlocal activism. Spanning the 1960s to the present day, almost all are recent acquisitions made under the direction of Joseph Becker, an associate curator of architecture and design. Studying them has been an ongoing focus for Becker, who joined the museum in 2007.

“The medium of the poster is not just print, but language,” Becker explains. “These posters don’t need to be considered ‘art’ but must be recognized for their artistry. They have become a critical element in organizing and activating communities in response to some of the most pressing issues of our time, bridging radical and populist movements, political dissent and ascension, and encouraging civic engagement and empowerment.”

“They also hold a record of our culture,” he adds. “They give us a chance to act, both as individuals and as part of a collective.”

We asked Becker to walk us through a few examples from the collection. The issues these posters represent are as varied as the tactics they use to express them, but all share a skill for rousing political imagination.