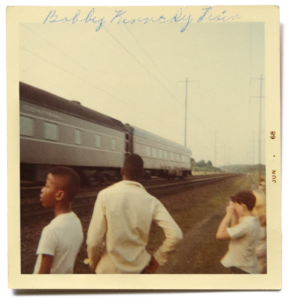

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed 2008; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Randi and Bob Fisher, Nion McEvoy, Kate and Wes Mitchell, The Black Dog Private Foundation, Candace and Vincent Gaudiani, Michele and Chris Meany, Jane and Larry Reed, and John A. MacMahon; © Magnum Photos, courtesy Danziger Gallery

Were you given specific guidelines or instructions to follow as you took the pictures?

My editor didn’t give me specific instructions. His job was to assign the project and it was up to me to make it work. When I got to Penn Station, all the trains were in a dark cavern filled with boarding platforms and steel staircases. A security guard checked my Look press credentials, then pointed toward an open door in a car saying, “Okay, get in that car, sit down and don’t move.” I was early. I was alone. My thoughts turned to Washington and the burial and the crowds and the press. Would I be there early enough to get set up with good access to photograph? No one knew I would be there. There was no way to get help. It was quite a while before other people entered the car. My mind was still stuck on the burial. Slowly people filled the car—no famous people, no press or TV, and only one other photographer. The doors closed. The train slowly moved through the dark tunnels under New York. Then suddenly it broke out of the tunnel into daylight and I was astonished.

What is your memory of seeing people by the tracks for the first time?

When the train came out of the tunnels, the first thing I saw was hundreds of people in mourning crowding together on platforms, almost leaning into the train to get close to Bobby. I was just overwhelmed, I had no anticipation of this at all. It was like an explosion. I jumped out of my chair and pulled the window down and started photographing this incredible mass of people who came to show their love and appreciation and sadness and loss for someone that I also was feeling great loss for.

What was your technique in capturing crowds of people from a moving train?

There were people everywhere. There was no pushing from what I remember. It was solemn and quiet. No yelling. I stood in the same spot on the train until it got dark and I photographed everything I saw on the track that day. I began to concentrate on tracking the subjects in every photo to lessen the effects of the train’s motion, hoping that I would be lucky enough to get a few usable photos. Later, I spent a long time editing and sequencing to try to have the flow of the photographs mimic my experience of looking out of the train window and feeling everyone going by me.

What is your favorite photograph from this series?

Your question is often asked but very difficult to answer, especially when the story is very powerful, emotional, and inherently dramatic and notable. Can one photograph alone reveal, ignite, bring to life the enormous power of pain, passion, confusion, anxiety, a swelling tragic loss of hope and dreams roaring through the ravished crowds? I doubt it.

But if I have to make a choice, I would say the father and son standing and saluting in front of a small footbridge, with the mother standing nearby on a dirt road. That’s the one that really gets me. They’re poor and have had hard lives, but are proud of what they have accomplished and grateful for the commitment and hope Bobby nurtured in the legions of the poor, the blacks, and countless other forgotten Americans. It’s the whole story of America right there and the founding of a country and the people growing in it, and what happens. For me that seemingly humble and ordinary situation radiates with love, loss, sorrow, gratitude, and a strength that will continue to help build the society that Bobby envisioned for everyone. This photograph exudes the determination and imagination of the hundreds of thousands who traveled to a new land with dreams of a new world that would be more just for everyone. I think it is a very good photograph; it has a strong, compelling story that makes me feel and understand and reflect on life.

Why do you think it took so long for your RFK funeral train photographs to be fully discovered and celebrated?

I was on staff with Look, and at that time magazines owned the photographs of the stories they financed. When I returned to New York to get the film developed, Look was in a high state of activity trying to produce stories about this tragic event in an extremely competitive industry. It was published biweekly, and was at a disadvantage with the weekly magazines. To keep from looking late with news events, they had to present stories in a different way. The editors liked my photos, but they assumed Life would do that story and publish it first. Their solution in the moment was to do stories about Bobby’s life. Look folded about three years later and never found a reason to publish the photos before that.

I tried for years after that to get the RFK photos published, but no magazine ever showed interest until 1998. Magnum Photos approached George magazine for the thirtieth anniversary of Bobby’s death and they published a ten-page story. The photos have been published in many magazines since then, and appeared in two books and quite a few exhibitions in the United States and Europe. I have no idea why there was no interest for thirty years.

Has anyone ever recognized themselves in one of the pictures and approached you?

I have often wondered if anyone who saw the train found themselves in a photo, but no one has ever contacted me to let me know.

How do you feel about these photographs so many years later?

It was a terrible, awful situation, and the loss of a very great man—a great man and a culture, and a great loss to the family. I think it’s one of the most important series that I have done. I’m very proud of the photographs and I think they’ve held up. I was very lucky but I think I did a good job.