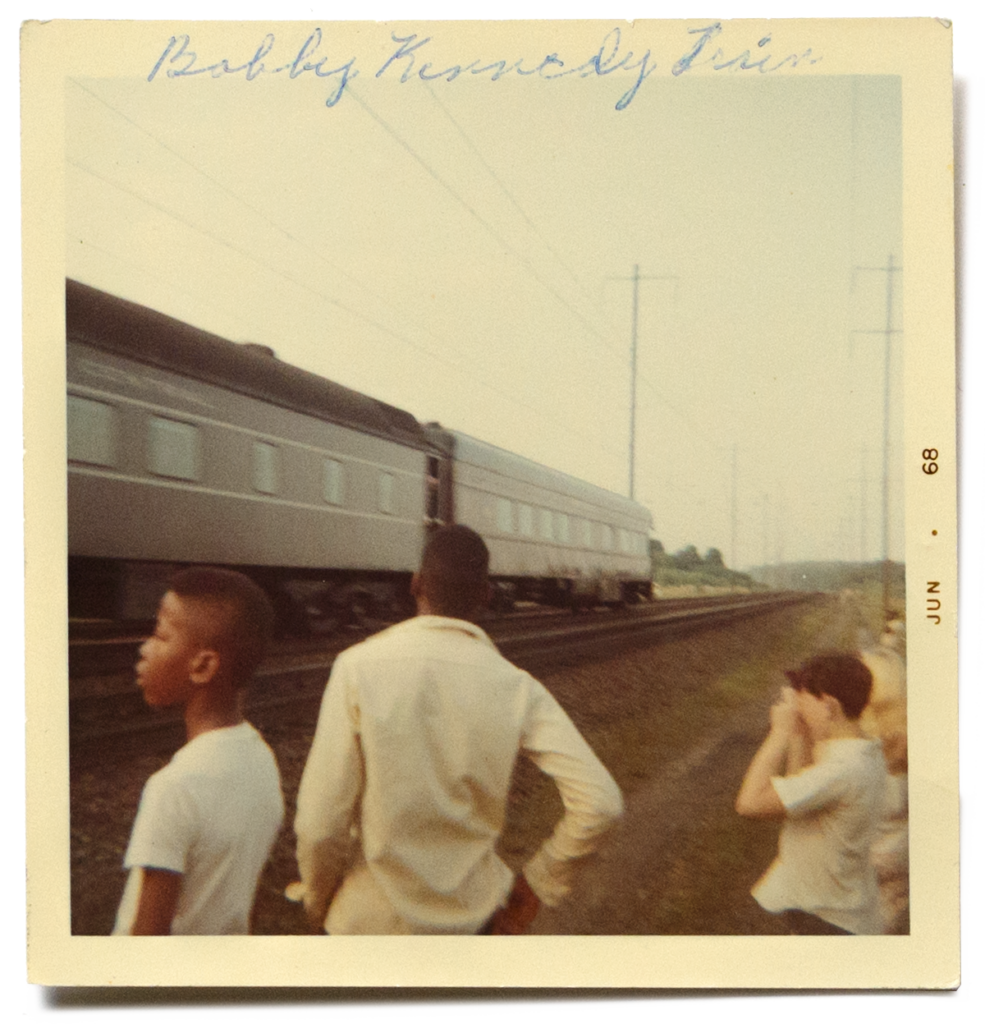

Philippe Parreno, June 8, 1968, 2009 (film still); © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Maja Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

On June 8, 1968, a funeral train carrying Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s body traveled from New York City to Washington, D.C. He had been assassinated three days earlier and was to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. This was just two months after Martin Luther King Jr. was killed and five years after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Bobby’s older brother. The train’s journey became a spontaneous memorial, as thousands of mourners gathered along the tracks to pay their last respects to a man who had been a symbol of hope for the nation.

“Memory is always reinventing history. Memory is how we see history in the present day.”

The Train: RFK’s Last Journey looks at this historic event through three distinct projects: color photographs that photojournalist Paul Fusco took from the train; snapshots and home movies by the spectators themselves, collected from 2014 to 2018 by Dutch artist Rein Jelle Terpstra; and a 70mm film reenactment of the train’s journey by French contemporary artist Philippe Parreno. This exhibition is the first time all three works will be shown together. While Fusco was not the only photographer taking official shots of the funeral that day, his photographs provide a unique view of the event. Terpstra’s research project and Parreno’s film each provide another. As Clément Chéroux, senior curator of photography, says, “The history of the event should be built through all these different documents, and all these different views.”

Paul Fusco: RFK Funeral Train

Magnum photographer Paul Fusco was on the train that day in 1968. He had been commissioned by Look magazine to cover the event. “There is a unique light in Fusco’s photographs that we don’t find in the other images that were made on the train that day,” observes Chéroux. This light came from Fusco’s focus on people, both in how and what he photographed. His images’ distinctive appearance came from how he followed people with his camera, which created a unique blurring effect around them. It was unusual at that time to see blurring in photojournalism. Perhaps because of that, it wasn’t until 1999 that the images were first published together as a collection, titled RFK Funeral Train. SFMOMA is acquiring 26 of these photographs, and a selection of them will be on view in the exhibition.

By focusing on the people watching the train as his subject matter, Fusco was able to capture something that other photographers missed. “I was trying to show what it meant to them [to be] there, what they were feeling,” Fusco says, “their love and appreciation and sadness and loss for someone that I also was feeling great loss for.” Kennedy had represented a chance that the country could come together, and Fusco’s images show just that: diverse communities gathering together to mourn. “This was during the civil rights movement, a period of great racial tension and strife,” says Linde B. Lehtinen, assistant curator of photography, “but through his death, there was a remarkable unity.”

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed 2008; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Randi and Bob Fisher, Nion McEvoy, Kate and Wes Mitchell, The Black Dog Private Foundation, Candace and Vincent Gaudiani, Michele and Chris Meany, Jane and Larry Reed, and John A. MacMahon; © Magnum Photos, courtesy Danziger Gallery

Rein Jelle Terpstra: The People’s View

Rein Jelle Terpstra saw Fusco’s images and was immediately fascinated. Looking closer, he noticed that many people in the photographs were holding cameras. “I thought, ‘How would it be if I could look through their eyes, through their cameras?’ And that’s where it started,” Terpstra says. He used Facebook to crowd source information and began getting in touch with people who were there that day, launching a multiyear project: The People’s View (2014–18).

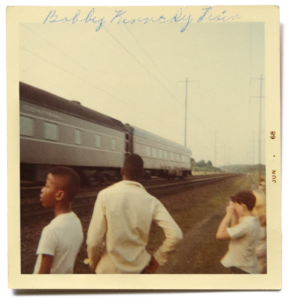

Terpstra is interested in the public archive, and the tension between history and memory. This collective memory, the circulation of these personal, vernacular photographs that people have held onto and passed down is “how moments like this in history are kept and made tangible,” says Lehtinen. By looking at these home movies, color slides, blurred snapshots, and even the notes and captions written on the photographs, a different view of history emerges, one that is both personal and universal. “It’s easy to get the official point of view,” says Chéroux, “but this is part of a new way of writing history, to give the people a voice.”

Annie Ingram, Elkton, Maryland, 1968; from Rein Jelle Terpstra’s The People’s View (2014–18); courtesy Melinda Watson

Philippe Parreno: June 8, 1968

Philippe Parreno takes yet another view of the train and its journey. A leading contemporary artist from France, Parreno is more interested in the metaphor of that moment. His seven-minute film, June 8, 1968 (2009), recreates Fusco’s images, imbuing them with movement and reimagining the event from an almost otherworldly perspective.

In the film, there is a sense of floating and looking down on the people in the landscape because the camera is positioned above the train. It is as if, according to Parreno, we are seeing “the point of view of the dead.” There is also another kind of floating, a hovering or tension between still and moving images. Parreno directed the actors in his film to stand still, looking not at the camera, but instead at a painted target on the train. The people are still and the objects around them — the train, the trees, and the grass — are moving, creating an uncanny effect.

Parreno’s film acts as a deconstruction of photojournalism. “He is suggesting that we need something else today to describe what happened then, and still photography is not enough. We need sound; we need moving images. Between Fusco and Parreno there is the same difference as between history and memory,” says Chéroux.

Philippe Parreno, June 8, 1968, 2009 (still); © Philippe Parreno, courtesy Maja Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation

This is a sentiment the curator shares. Mixing or blurring — between photographs and videos, light and sound, snapshots and artistic works — is something Chéroux is very invested in as he plans future exhibitions at SFMOMA. “I’m interested in trying to erase the hierarchy and the boundaries between all the different types of photography,” he says. “Photography is an object, but photography could also be something else.”

The Train: RFK’s Last Journey is on view on Floor 3 from March 17 through June 10.