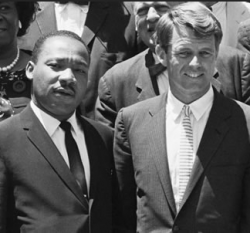

Annie Ingram, Elkton, Maryland, 1968; from Rein Jelle Terpstra’s The People’s View (2014–18); courtesy Melinda Watson

Mike Dixon first met Rein Jelle Terpstra in a bowling alley parking lot in Elkton, Maryland, in 2015. Terpstra, an artist from the Netherlands interested in the connections between perception and memory, had come to town the day before doing research for The People’s View (2014–18). The project aimed to collect photographs, home movies, and stories from people who had witnessed Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral train as it traveled from New York City to Washington, D.C., on June 8, 1968.

Terpstra had been hanging around an out-of-service train station in Elkton, looking for people who had been there that day 50 years ago. When he noticed the Elk Lanes bowling center across the street, he went over to investigate and saw senior bowling on the schedule for the next morning. Returning early that day, he approached the man at the desk, who took the microphone and introduced him over the loud speakers. While friendly, the bowlers didn’t have any train photographs, but they did have a suggestion: call Mike Dixon. Terpstra reached out to Dixon, who told him, “Hold on, wait half an hour there. Don’t move.” And he interviewed Terpstra with a reporter from the Cecil Whig, a local paper, in the parking lot. After that initial meeting, Dixon began helping Terpstra find leads in Cecil County.

A local Maryland historian specializing in social and community history, Dixon says, “My whole practice is around the people who do not make the headlines. And [Terpstra’s] not looking for the professional journalists, the photographers, the politicians; he’s looking for the memories of everyday people.”

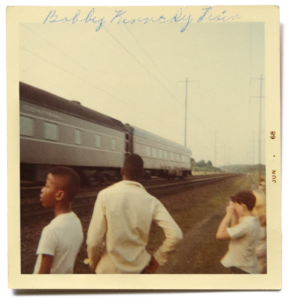

Terpstra’s project was inspired by Paul Fusco’s famous RFK Funeral Train photographs, taken from onboard the train transporting Kennedy’s body for burial at Arlington National Cemetery after his assassination. Fusco, who had been commissioned by Look magazine to document the journey, focused in on the crowds that gathered along the tracks. His powerful images show diverse communities coming together to mourn a man who symbolized change and hope for the nation. Just two months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and five years after losing John F. Kennedy, Bobby had been taken as well. Looking closely, Terpstra noticed that many people in the photographs were holding cameras and decided he wanted to view the event through their eyes.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968, printed 2008; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Randi and Bob Fisher, Nion McEvoy, Kate and Wes Mitchell, The Black Dog Private Foundation, Candace and Vincent Gaudiani, Michele and Chris Meany, Jane and Larry Reed, and John A. MacMahon; © Magnum Photos, courtesy Danziger Gallery

Terpstra began his project using traditional research methods, reaching out to libraries and archives, but soon, he says, “I realized that this whole project was not institutional. No one ever collected these kinds of images.” So instead, he began using Facebook and other social media sites to crowd source information, joining online groups from locations along the train route, and then visiting the towns and people he found.

From that cold call at the bowling center and through his connection with Dixon, Terpstra made several other contacts and memorable finds. Indeed, these personal connections — between people and their collective memories — became an integral part of the project.

“The most spectacular find came out of a storage locker,” says Dixon. “There was this reel of 8mm home movies that hadn’t been seen in nearly 50 years. This young guy, Larry Beers, who was about 15 years old at the time, had just received a movie camera that Christmas, and he shot a lot of home movies. He insisted that he had one of the funeral train. We go out to his storage locker, and he’s crawling through stuff, and comes out with a large box of movies. And, sure enough, there it was.” They had found a three-minute piece of time that would otherwise have been lost.

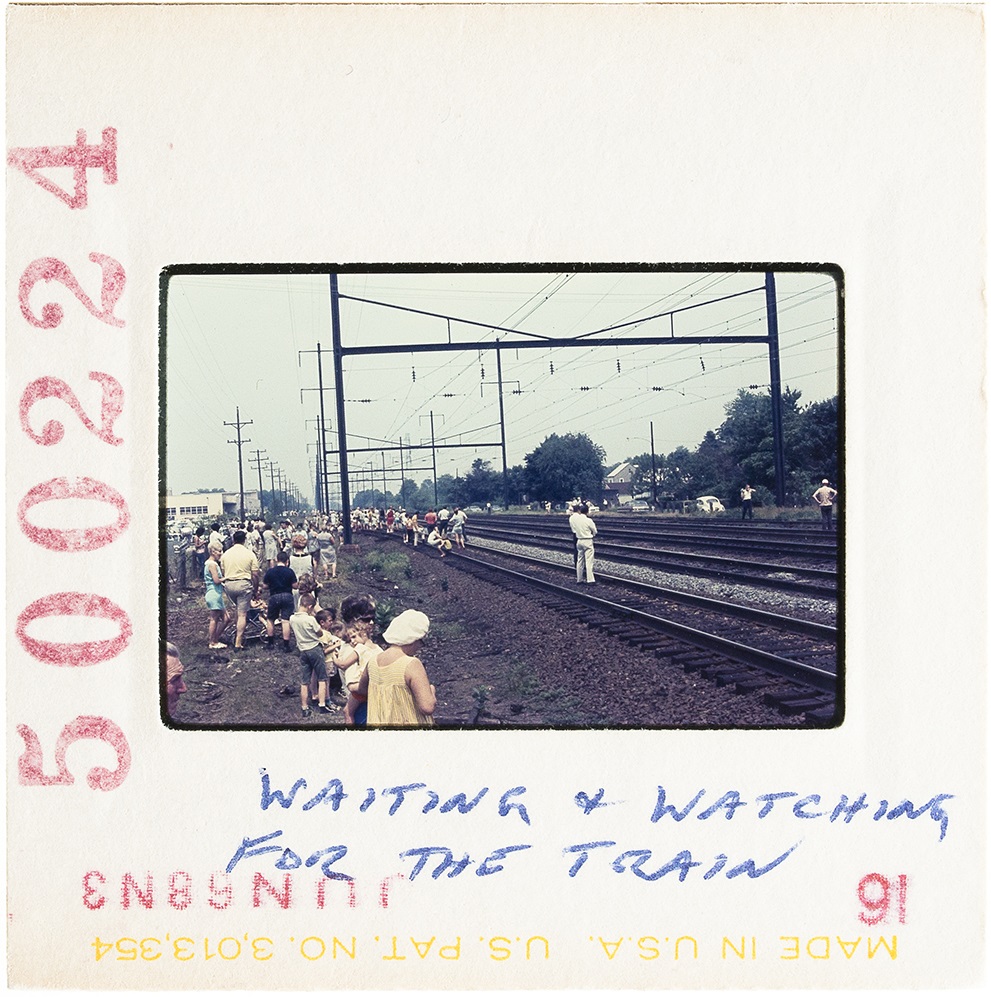

Like Beers, Dixon was 15 years old when the funeral train passed through Cecil County. “It was this little Maryland station, but there were hundreds of people, including me, sitting along those tracks . . . the whole community turned out,” he says. “[The train] was three or four hours late. Besides the fact that the year is one you don’t forget, it’s just the kind of day you don’t forget, sitting and waiting for that train to come through.”

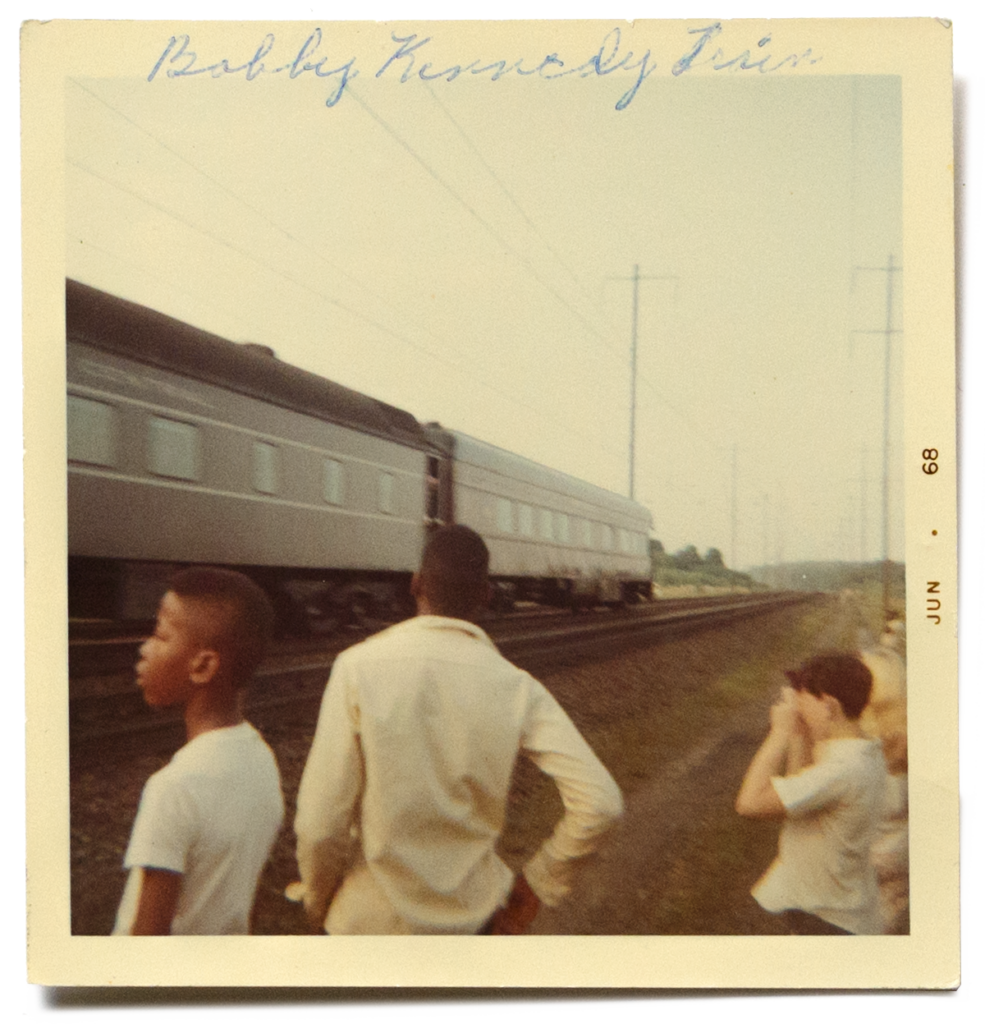

William F. Wisnom, Sr., Tullytown, Pennsylvania, 1968; from Rein Jelle Terpstra’s The People’s View (2014–18); courtesy Leslie Dawson

Dixon introduced Terpstra to Michael Scott, who also grew up in Cecil County and witnessed the funeral train. Terpstra and Scott bonded over their fathers’ mutual admiration for RFK and his willingness to take a stand on civil rights issues, including sending troops to protect the Freedom Riders. Michael Scott’s father, McKinley Scott, was head of the local NAACP at the time and heavily involved in the movement. He made sure his children were the first to integrate into the school system. Scott had his own strong connection to Kennedy. He remembers seeing him give a speech at the Democratic Convention, and how he stood humbly while people continued to applaud: “I thought, ‘This guy, he must really be somebody.’ That, combined with the fact that, here’s this guy who lost his brother, his president — he stands up to power structures, he sends federal troops in to [keep] people who look like me safe, and now he’s going to run for president.”

On June 8, 1968, Scott was watching the news and saw that the train was coming. He told his mom, who was in the kitchen making apple pies, that he was going, and she immediately took off her apron to join him. “It just felt like I had to be there because it was only a mile away,” he says. “I’ve read you don’t know the value of a moment until it becomes a memory. I think everybody there knew that this was a valuable moment. I knew it.”

With Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy gone, Scott felt like Bobby had been the last hope. They had lost someone who, like Scott’s father, was willing to take a stand. Four weeks after the funeral train, a bomb was thrown at the Scotts’ home from a passing car in an attempt on his father’s life.

Looking back now, Scott sees progress. “I’m encouraged about the United States of America, in spite of what people say,” he says. “Coming up on 50 years since Bobby, I think it’s important to see where we are today by going back to where we were then. I know for a fact I’ve had opportunities that my father probably wouldn’t have had when he was young.” Scott sees Terpstra’s project as an important part of revisiting this moment. He says, “Paul Fusco and the [other documenters], they’re looking at it train out. [Terpstra’s] looking at people train in, at their collective memories.”

The two have become good friends, and Scott joined Terpstra for some of his research. He recalls one occasion where they went to meet someone with footage in a part of town that made him feel uncomfortable. A skinny man came out of the house with two tough-looking dogs. Scott thought the guy might be a Ku Klux Klan member and decided to stay in the car. When they couldn’t find the footage, Scott told Terpstra he didn’t want to go back. Later, he realized he’d read the guy wrong. When they returned, he says, “The same gentleman got me a chair, sat me down, and handed me a beer . . . I don’t know if you know anything about the South, but if somebody gives you a beer and you’re a first time visitor, that’s pretty good.”

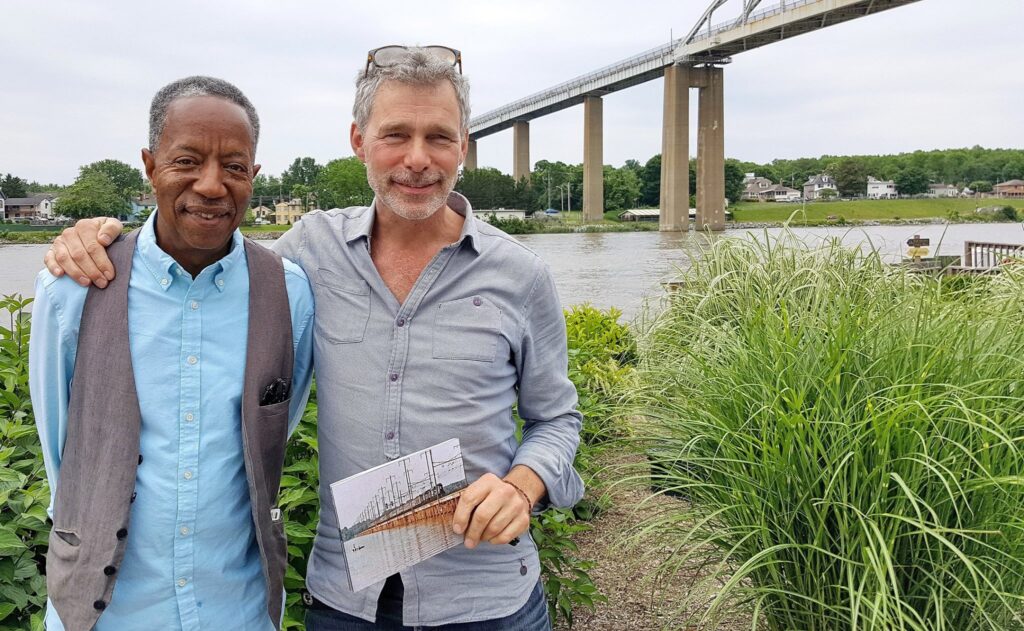

Michael Scott and Rein Jelle Terpstra; photo: courtesy Mike Dixon

Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral train brought people together through grief, and now Terpstra’s project is bringing them together through remembrance. Terpstra envisions the work as a reconstruction of the funeral train’s journey through shared stories and images, connecting memories the way the train stops are connected by tracks. He aims to create “a continuous line of people, shoulder to shoulder.” And, through the people he’s met, and the personal relationships he’s fostered, that’s just what he’s done.

The People’s View is on display at SFMOMA as part of The Train: RFK’s Last Journey, March 17–June 10, 2018.

Add to the story by sharing your memories of RFK’s funeral train on our Facebook page or through our call-in line at 415.915.1731.