At the museum? Click here for a floor plan + full guide. Thinking about visiting? Read below for exhibition highlights.

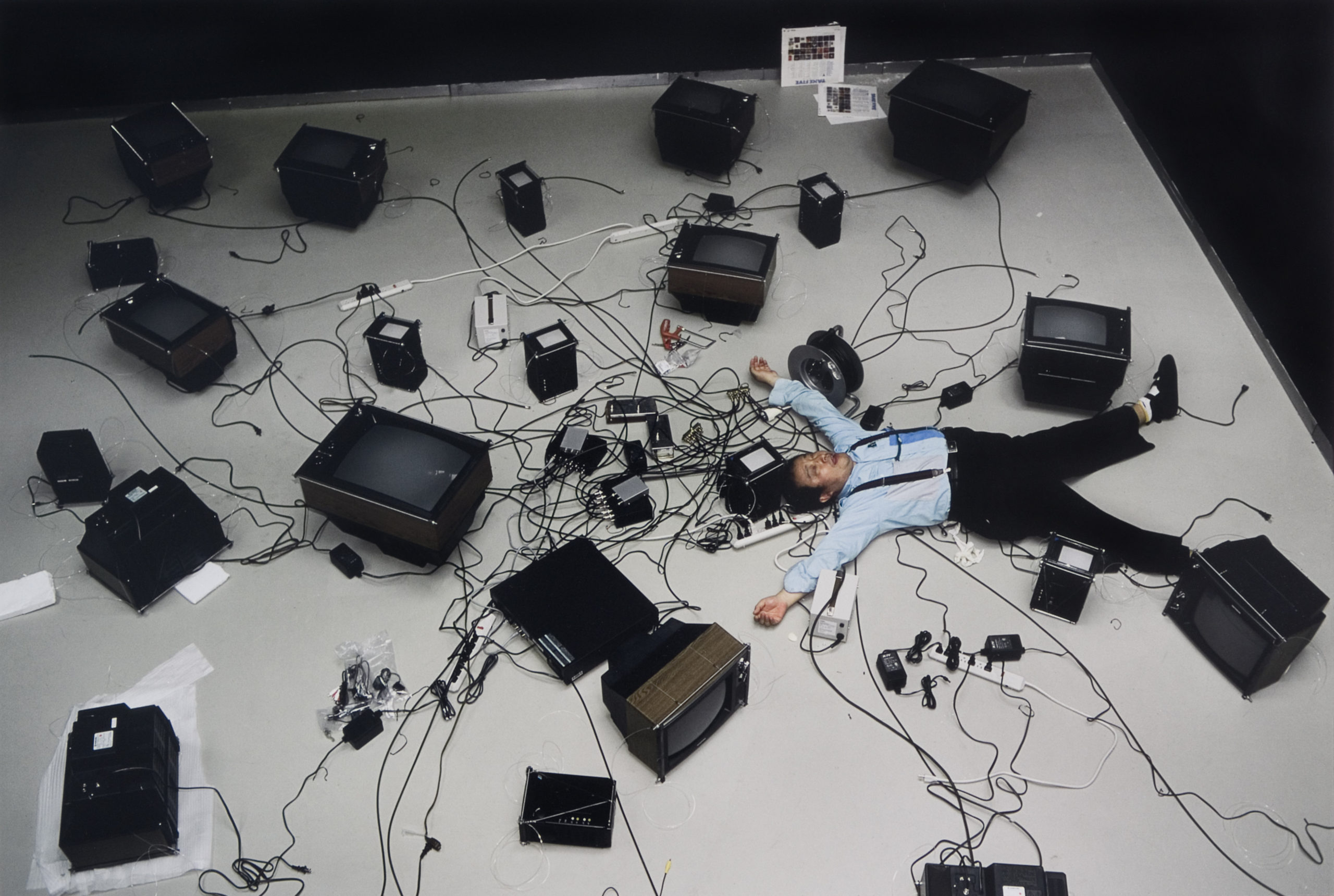

Nam June Paik lying among televisions, Zürich, 1991; photo: Timm Rautert

The “Father of Video Art”

Widely considered the “father of video art,” Nam June Paik (1932–2006) was born in what is now South Korea and spent much of his life in Japan, Germany, and the United States. The playfully rebellious artist trained as a classical composer; he sought to radically expand the parameters of art and defied genres and disciplines. Over his five-decade career, he worked with avant-garde artists and pop stars alike, and created groundbreaking video art, immersive installations, a family of TV robots, live broadcasts, participatory artworks, and more. Paik was a true and oftentimes humorous visionary who foresaw the importance of mass media and technology. “Someday,” he said in 1965, “artists will work with capacitors, resistors, and semi-conductors as they work today with brushes, violins, and junk.”

Nam June Paik, on view through October 3, 2021, is the first West Coast retrospective dedicated to the artist and brings together more than 200 of his works. Below, find a guide to five that serve as entry points to his career, selected by Curator of Media Arts Rudolf Frieling and Assistant Curator of Media Arts Andrea Nitsche-Krupp.

1. Sistine Chapel (1993)

Rome’s Sistine Chapel underwent a substantial and widely debated restoration process in the 1980s. Paik, when invited with artist Hans Haacke to represent Germany at the 1993 Venice Biennale, reimagined the iconic Vatican landmark as it was before restoration, swapping its biblical references with pop stars and using more than forty state-of-the-art video projectors. “Venice, the historic site of excessive riches of centuries of global commerce, provided the ideal stage for Paik’s updated take on the circulation of images and immaterial goods in contemporary society,” says Frieling.

Restaged here for the first time, Paik’s Sistine Chapel consists of fast-paced and overlapping images that completely cover the gallery walls and ceiling—one of the most underappreciated parts of architecture, according to Paik. With its electronic visuals and booming audio, interspersed with periods of silence, the immersive installation stands in stark contrast to the experience of its namesake.

“His moving images occupy literally every corner of the space in a blurry, irreverent, and provocative way, remixing and summarizing his entire artistic career,” Frieling says. “Replacing fresco reliefs with fast-paced electronic images asks for a stretch of your imagination, but his version touched upon the actual experience of images distributed via mass media and the staging of an entertainment spectacle.”

2. TV Garden (1974–77/2002)

Deeply influenced by the Buddhist belief that all things are interdependent, Paik created TV Garden as a futuristic landscape where technology would become an integral part of the natural world. In this piece, television sets and live plants share a habitat. “TV Garden is one of Paik’s master works,” says Nitsche-Krupp. “It epitomizes one of Paik’s great strengths: the ability to revisit, permutate, and recombine ideas, images, and concepts into newly generative work.”

The work’s forty-nine television sets display Paik’s groundbreaking music video Global Groove (1973), a colorful mix of avant-garde, pop, and commercial imagery and audio that connects cultures and combines traditional and contemporary sources. Featuring Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, chants by the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, a Nigerian dance performance, and Japanese TV ads, Paik’s selection captures the disparate and sometimes overwhelming content of mass media to unpredictable results. “Despite the vast variety of content and pacing, it doesn’t feel like the overwhelming free-for-all you might expect,” Nitsche-Krupp says. “During install, the video was playing—and blaring—nonstop. I’m always charmed by the jubilant and meditative way it flows and sings.”

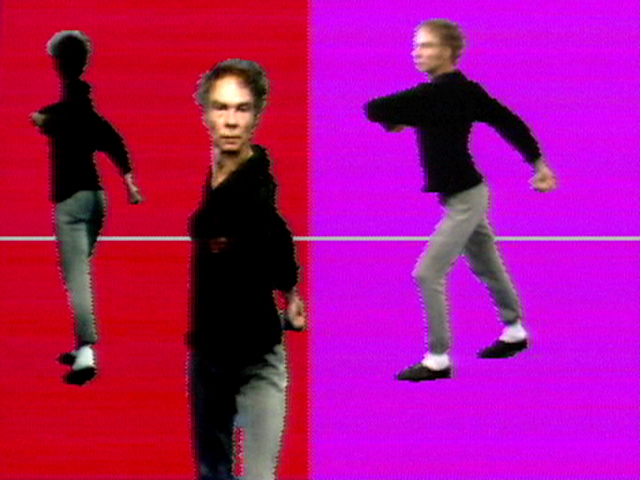

3. Merce by Merce by Paik (1975–76/1978)

Merce by Merce by Paik is a vibrant, two-part tribute to postmodern choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham, one of Paik’s many longtime friends and collaborators. “It’s full of love,” says Nitsche-Krupp. “It belongs to a larger category of work within Paik’s practice devoted to his friends, family, and collaborators—although those descriptors are, for him, often indistinguishable.”

Part One (1975–76) features choreography devised by Cunningham specifically for the video camera and manipulated by artist Charles Atlas, accompanied by a fragmented audio collage that includes the voices of John Cage (Cunningham’s partner) and artist Jasper Johns. In Part Two (1978), Paik and artist Shigeko Kubota (Paik’s partner in life) pay tribute to artist Marcel Duchamp alongside Cunningham. Combined, it creates what Paik referred to as a “dance of time.”

“Paik’s art and writing reveal a fascination with people and the way we relate to one another,” Nitsche-Krupp says. “Time, as an axis of artistic production and of lived experience, likewise held his curiosity. Here, he looks to friends and artists who were similarly transfixed by its nature.”

4. TV Chair (1968)

Paik predicted that video technologies would become so integrated into our daily lives that they would blend in with our living environments, taking the form of video furniture and video walls. TV Chair plays with this notion by proposing an absurd piece of video furniture. Here, a CCTV camera points down at a chair with a television under its transparent seat, which displays the live video feed. It is the most recent of Paik’s works to enter the museum’s collection, and a provocative, humorous one.

“TV Chair seemingly asks its beholder to sit down, a movement that would effectively prevent them from looking at the TV mounted under the seat,” Frieling explains. “So, would the ‘audience’ here be the individual’s behind? Is one supposed to interrupt the live image on a screen by fulfilling the implicit request to sit down? Is it a logical choice to either look or to sit?”

Great art asks questions without providing definitive answers, notes Frieling. “Far from being a matter of frustration, there is humor and a liberating moment in Paik’s conceptual and Zen-inspired practice,” he says. “The art will always be in the eye of the beholder; what we see is an absurd juxtaposition, and that makes the act of looking fun too.”

5. Zen for Film (1964)

How do you make a film without filming? Paik asked himself and his contemporaries this question in 1964, as avant-garde artists across disciplines radically pushed to question the limits and boundaries of their chosen mediums. Paik’s solution came in the form of Zen for Film, in which a blank 16mm film leader runs through a projector.

The work runs on a continuous loop in the gallery, though Paik first presented the blank film inside a cinema. In doing so, he encouraged the viewer to become aware of the physical aspects of the projection and viewing experience: dust and scratches on the film, the projector, the screen, oneself, and other audience members. When it was shown at the New Cinema Festival in New York in 1965, Paik stood in front of the projection, casting and watching his own shadow.

“Paik even recommended kicking the pristine new blank film around a dirty floor and letting it accumulate dust and random scratches to prepare the material for exhibition,” Frieling says. “He did not like things to be too perfect. In fact, he later claimed that, ‘When too perfect, lieber Gott böse,’ which translates to, ‘When too perfect, dear God angry.’”