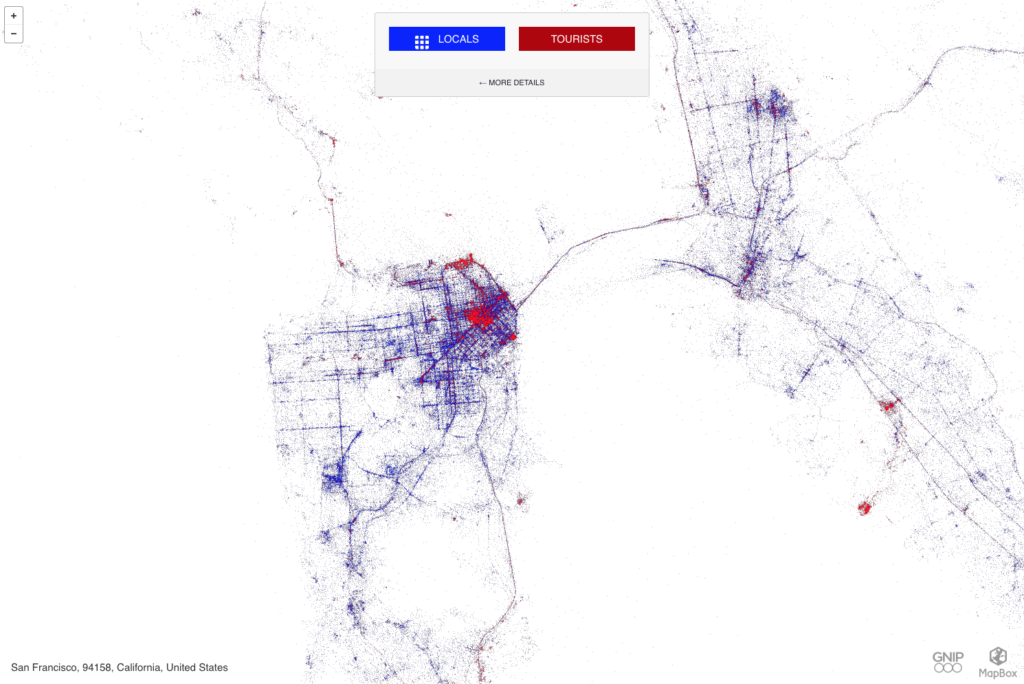

SFMOMA collection data visualization by Ian Heisters of Stamen Design

In recent years, some cultural institutions have begun exploring and developing public APIs for their museum collections. Within the last year alone, new or relaunched APIs have been produced by the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. SFMOMA will soon be adding itself to that list. These new APIs are part of an increasing global trend in releasing free and usable data. As “API” and other tech buzzwords become more common in a museum context, it can be difficult to sift through the jargon and the hype. So what is an API, and why build one for an art museum?

API stands for “Application Programming Interface.” These three words walk the line between perplexing and meaningless, but the fact that you’re reading this page means you’ve engaged in a process that relies heavily on APIs. An API is a set of instructions that specify how two software programs should communicate with each other. What makes an API valuable from the perspective of a museum is not what it does inside your computer, but instead how it allows users to request data from inside your institution and have it delivered to them in a usable form.

Getting to this webpage mirrors the request-response process utilized by many APIs. When you type a URL into an Internet browser, you are sending a computer a message. This message is processed and then, milliseconds later, the requested webpage is returned. A public API allows users to make requests for data and, like magic, get their hands on it. To demystify this process, we can begin by translating an API’s constituents — data, methods, arguments — into the modular building blocks of language — “nouns,” “verbs,” and “adjectives.” The “nouns” are the pieces of data or information the user wants. For museums, the “nouns” are things like artists, artworks, and exhibitions. The “verbs,” or methods, specify what we want our computer to do with the “nouns.” In an API, common verbs are “get,” “post,” “put,” and “delete.” How do we want them to be returned to us? Do we want to run a search? Finally, the arguments passed into the methods can be thought of as “adjectives” that specify the “nouns.” They tell the application with which we are interfacing more specifically what we want. How many objects should be returned in a search? What type of file do we want returned? In these terms, running an interaction is as simple as sending a complete message to the API, a method passed with arguments, a “verb” with some “nouns” and “adjectives,” for example “Get all the artworks.”

//code has been edited for clarity

{

//The start of the response object

"statuses": [

{

"metadata": {

"iso_language_code": "en",

"result_type": "recent"

},

"created_at": "Thu Sep 18 20:15:15 +0000 2014",

"id": 512696373632716800,

"id_str": "512696373632716801",

"text": "RT @SFMOMA: Thanks for joining us today!@ybca @MoADsf @Jewseum @SFJAZZ #FutureSFMOMA",

//Information about the user who posted the tweet

"user": {

"id": 44534206,

"id_str": "44534206",

"name": "Gianmarco Castillo",

"screen_name": "CiudadAzafran",

"location": "Lima Peru",

"description": "Productor audiovisual de https://t.co/9Jt8L7TWNF. Edito vídeos con cariño, escribía por mera curiosidad.",

"entities": {

//Hashtags included in the tweet

"hashtags": [

{

"text": "FutureSFMOMA",

//This hashtag starts at the 59th character in the text

//and spans to the 72nd character

"indices": [

59,

72

]

}

],

"symbols": [],

"urls": [],

//The users mentioned in the tweet

"user_mentions": [

{

"screen_name": "MoADsf",

"name": "MoAD",

"id": 19944715,

"id_str": "19944715",

"indices": [

34,

41

]

},

{

"screen_name": "Jewseum",

"name": "The CJM",

"id": 19837036,

"id_str": "19837036",

"indices": [

42,

50

]

},

{

"screen_name": "SFJAZZ",

"name": "SFJAZZ",

"id": 130932591,

"id_str": "130932591",

"indices": [

51,

58

]

}

]

},Code snippet from a request made to Twitter’s REST API using the parameter “futureSFMOMA”on the “get” method and the argument “search/tweets.” We used the value of five for the optional count parameter, so five tweets were returned. This is an example of the code for the JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) response object of one of the tweets.

This request-response mechanism has made the development of public APIs particularly compatible with the recent acceleration of app development. Many popular websites, including Twitter and Facebook, have made their APIs public, with the hopes that third-party users will use their data for development projects and building apps. For example, the website Etsy uses the Twitter API to integrate the shop owners’ Twitter accounts and activity into their site. The app RunKeeper allows users to track and share their fitness stories on Facebook.

While these applications are more directed toward research and general exploration, public transit companies show the profound utility of APIs. San Francisco’s metro rail system, BART, has a public-facing API. While BART riders expect convenient access to system maps, ways to plan trips, and real-time information on train arrivals, BART does not actually provide these services themselves. More than 100 smart phone applications, such as iBart, BayTripper, and HopStop, have used the BART API to create apps from the public data. By releasing a public API, BART enhances BART user experience and popularizes its services, but without actually expending their own resources on app development.

BART fully capitalizes on the development atmosphere with its API, but why would a cultural institution such as a museum want an API? Publicizing and providing accessibility to data can involve complications with copyright and sharing private or sensitive information. Furthermore, APIs cost money and resources to make and maintain. Whether or not an API is appropriate for your institution can be made clear from the museum’s mission. In our case, “SFMOMA is dedicated to making the art of our time a vital and meaningful part of public life.” Museums are primarily outward-facing institutions, a characteristic that becomes the foundation for everything the museum does. Museums also are homes to massive amounts of data: about their physical objects, people involved at the institution, their programming, and their history. At their core, most museums cohere perfectly with the current trend in open data, which is about making data available and usable to the broadest possible audience. A museum’s API has the potential to do just this.

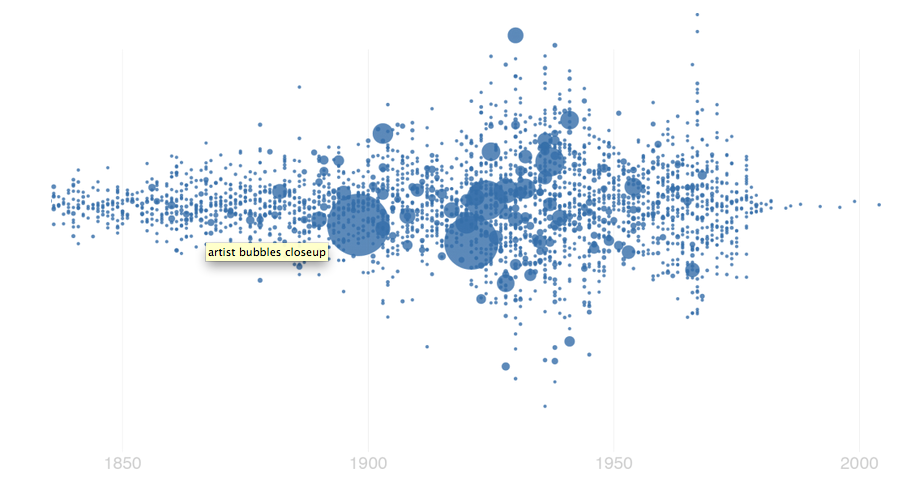

In making the data public and usable, the museum’s API, like the museum itself, becomes a platform for open, hands-on exploration. In October 2013, Tate in London released a public API on GitHub, a website for sharing repositories of computer code. GitHub is a popular platform, and the release of an art museum’s dataset sparked interest and dialogue among developers. Florian Krautli, a researcher from London, who focuses on visualizations of cultural data, created several graphs and charts visualizing the breakdown of the collection by date, artist, and other qualifiers. Unusual patterns and characteristics about the collection and about the data itself emerged. He quickly discovered that most of the collection — a mind-blowing 57 percent — is made up of works by William Turner. He also found a high concentration of works dated 1814, which, it turns out, resulted from a large group of undated works by William Daniell being somehow labeled (or mislabeled) with that year.

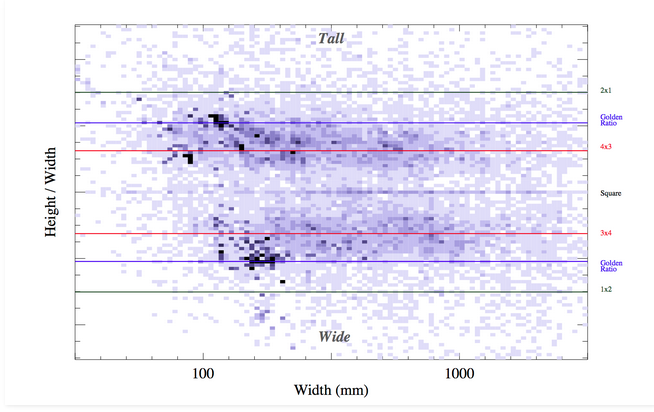

Jim Davenport’s visualization of the Tate’s collection according to artwork dimensions

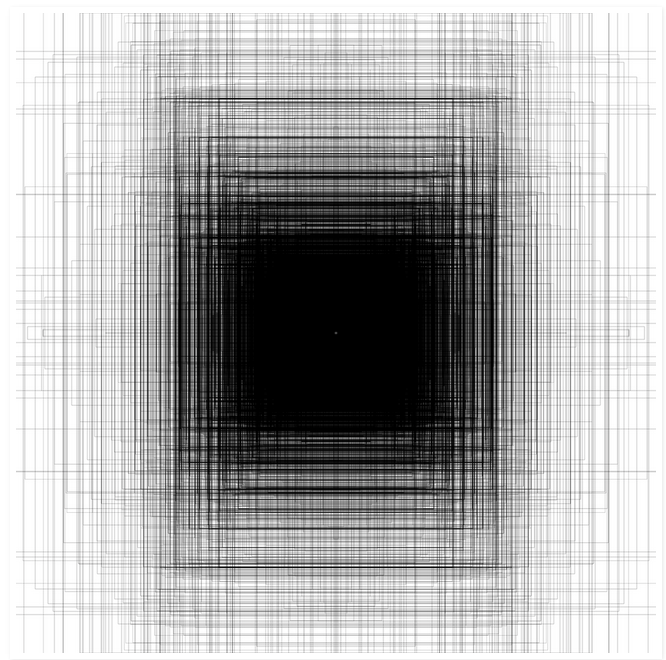

Jim Davenport, an astronomy PhD candidate from Seattle, found the data about artwork dimensions particularly compelling. Using the Tate’s API, he created a visualization mapping sixty-five thousand artworks by size. Within the visualized data, Davenport was able to see several intriguing patterns, including a clustering of artworks that were created in the Golden Ratio. He then used the data to create his own work of digital art, in which each piece in the collection is represented by a black rectangular outline scaled to the artwork’s dimensions, one outline superimposed on the next.

Jim Davenport’s alternative visualization of the Tate collection according to artwork dimensions

These visualizations of the dataset are only two examples of how a public collection API allows for the innovative combination of art and data, and in many ways they embody why a museum would want to build an API — to allow people to creatively engage with its collection in the digital space. In order to establish fertile ground for exploration, museums must attempt to predict what people might want to do with their API. As museums develop their APIs, the process is rife with decisions about what data should be available and how it should be designed.

As SFMOMA continues its own API development, we will be asking and answering such questions. You can follow our progress on this site, where we will be adding research, visualizations, and code as we develop our Collection API. If you have any questions or feedback, you can find us on Twitter at @SFMOMALab.