Shomei Tomatsu: The First Decade

Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

June 2006

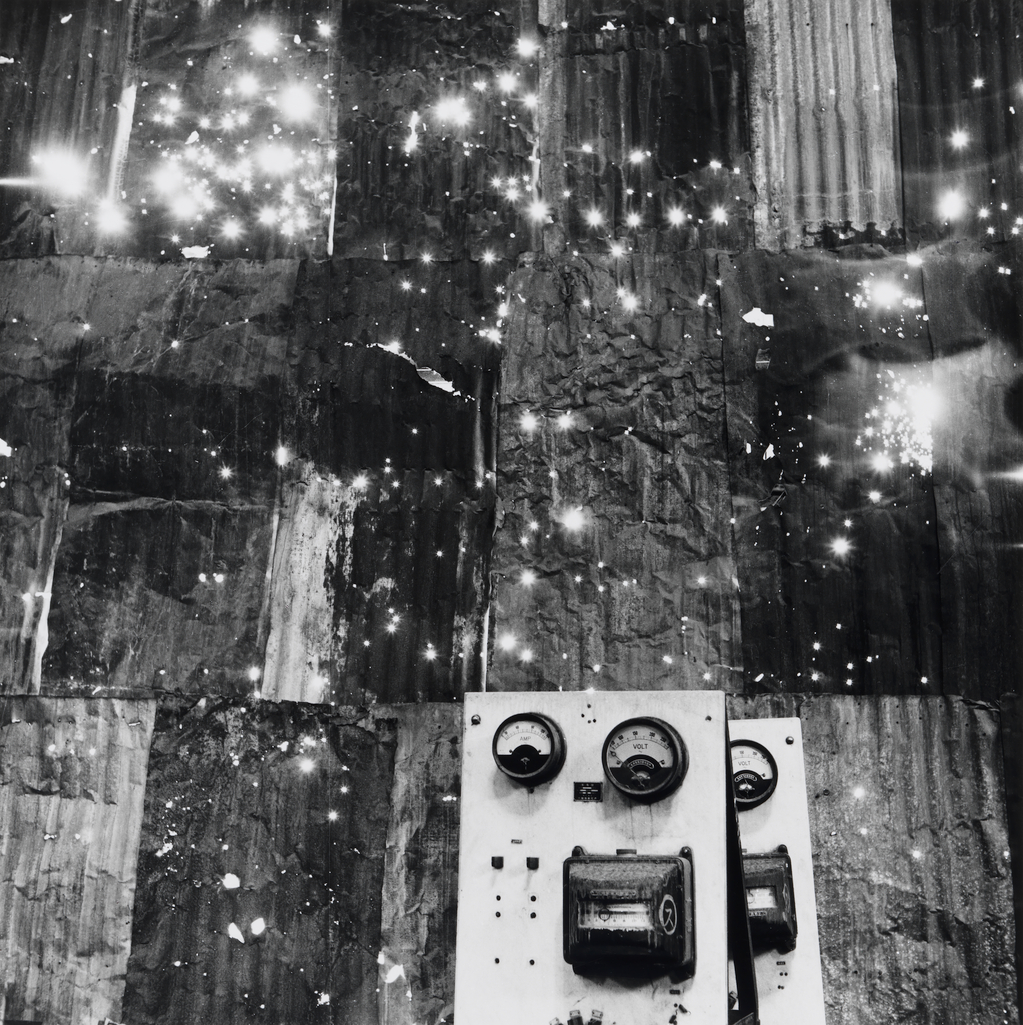

Shomei Tomatsu: I’ve been holding a series of “mandala” exhibitions of areas of Japan that I’ve been drawn to and come to love over the years. As you know, mandala is a term from esoteric Buddhism, a visualization of the universe, a spiritual microcosmos. This is my own image of the cosmos, my image of the world.

Shomei Tomatsu, the most influential photographer of postwar Japan, was born in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, in 1930. He began photography in 1950, as a university student. Japan was still in the early stages of recovery from World War II.

Tomatsu: My “original landscape” was immediately after the war. Japan had lost the war, become a defeated nation, and the Allied occupation army, led by the Americans, landed in force, and the occupation began. I was fifteen at the time, molting from a boy to a young man, an impressionable age. It was just chance that I came along at that time, but I suffered a deep culture shock. That became, for me, my “original scene,” my “landscape.”

Firebombing had burned the center of the city to the ground; countless people had died. It was a burnt plain. There was nothing to eat, no clothes to wear. It was the depth of poverty, right after the war. That’s when I started photography, and the scenes of utter devastation were seared into my eyes and always remained in my memory. To pursue the war, in the name of boosting the fighting spirit, adults distorted the news. They said Japan would defeat the Americans and British, that we’d surely win the war, but Japan lost. They all lied. What it came down to was, the only things I could believe in the world were the actual things I saw with my own eyes. I could accept facts as long as I had seen them with my own eyes.

What drew me to photography was this undercurrent in my consciousness, a deep skepticism about the world. Photography is objective in this way. It records things as they are.

In 1954, Tomatsu took a job as a staff photographer at Iwanami, a publisher that specialized in inexpensive books of photo essays. He continued to mine the experiences of his youth as material for his books.

Tomatsu’s first books:

Floods and the Japanese (1954)

Pottery Town (1955)

Tomatsu: The 1953 typhoon was the first flood I experienced. My own home wasn’t affected, but the home of one of my professors was flooded. It was in the town of Isshiki. So I saw the flood in Isshiki with my own eyes. I had just begun photography, and I took lots of photos. Then the Ise Bay typhoon hit Nagoya. It killed over five thousand people. Floods were that frequent. “The country is torn apart, but the mountains remain,” as they say. Japan has suffered floods and earthquakes that were so massive they overwhelmed the capacity to respond. The Ise typhoon destroyed my family home, and that led me to do the series Home.

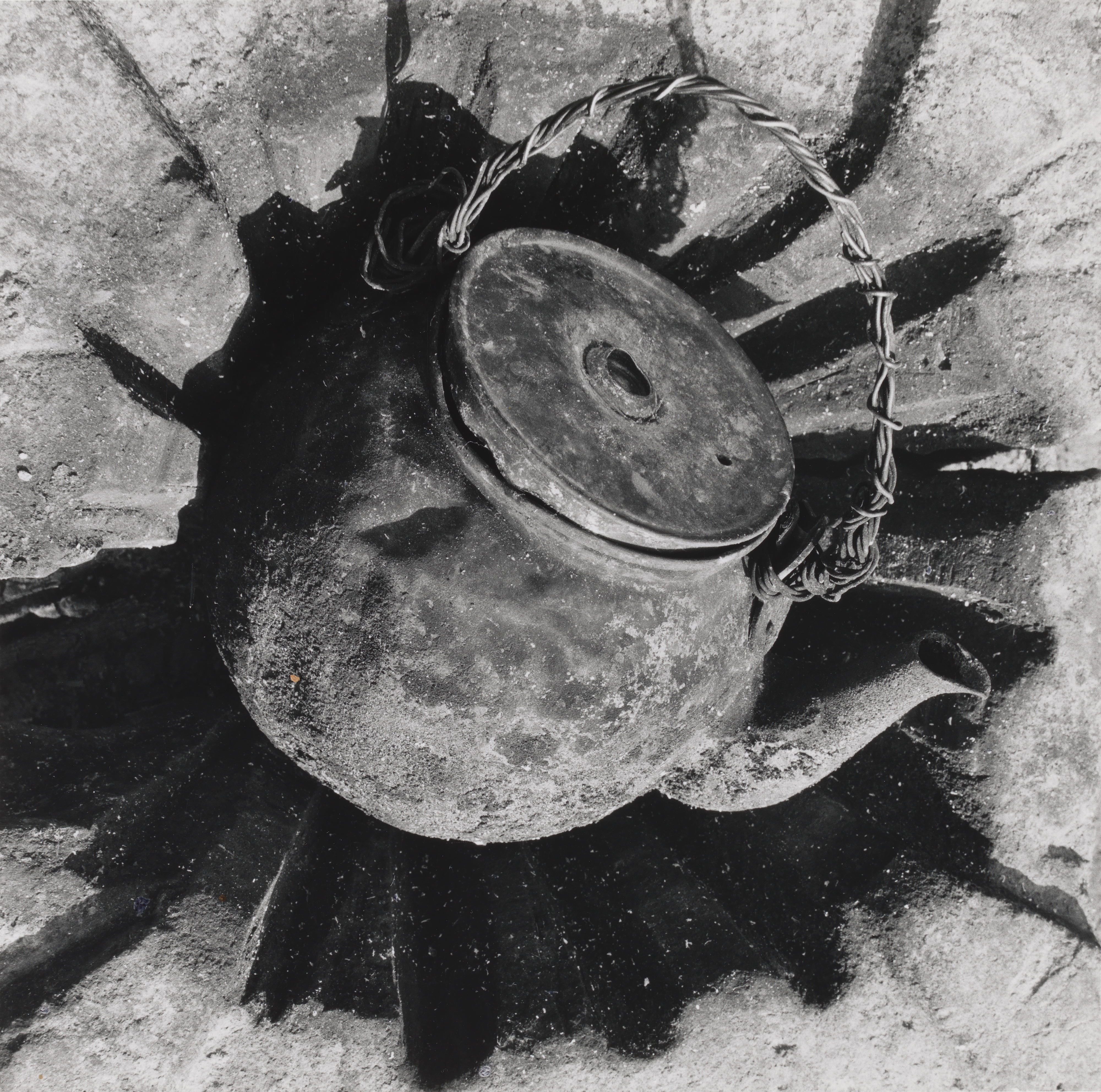

I often visited the pottery town Seto in college, before I started photography. So I was familiar with the area. When I began photography, the town was distinctive, a town sustained entirely by the pottery industry. But it’s primarily small factories, run by just one family, or a group of relatives. That’s what drew me there. It was the tail end of coal-fired energy. They said the sparrows in Seto were pitch black . . . the sky was sooty all day long, from all the smoke. Chimneys filled the landscape. They were burning coal. Around 1960, a petrochemical plant was built in Yokkaichi. This was the period of transition to oil-based energy in Japan. So the two sets of images epitomize this period of transition.

Tomatsu went freelance in 1956. He published a succession of prominent series in photography magazines.

Tomatsu: I started with Local Politician, then Section Chief. I did a series on elementary and high school principals. A series on village elders, another on a lighthouse operator. People in a variety of positions of responsibility. I later culled a series called The Japanese for my first exhibition. The subjects were born in the early twentieth century, and they were all men.

I realized many years afterward that it was a search for a father, my own father. I lived apart from my father; I grew up without knowing him. So, unconsciously, I was groping to find an image of my father, and I found it in men of that generation.

In the early years after the war, Japan was very poor. Then, there was the transition to oil, a boom that began with the Korean War, rapid growth that made Japan the second-largest economy in the world. But that earlier era was so poor . . . and yet, people’s faces were so bright. Fifty years ago, young people were really vibrant. There was nothing, a wasteland, and they had to rebuild Japan, they had to rebuild the very town they would live in. That was the kind of time it was . . . and it was reflected in people’s faces.

When walking around, camera in hand, feelings determine which way you go. Choosing left or right at a crossing, it’s mostly instinct. “I’ll go that way.” And the path I choose usually leads to an encounter. I don’t know what it is . . . I guess I’m lucky.