-

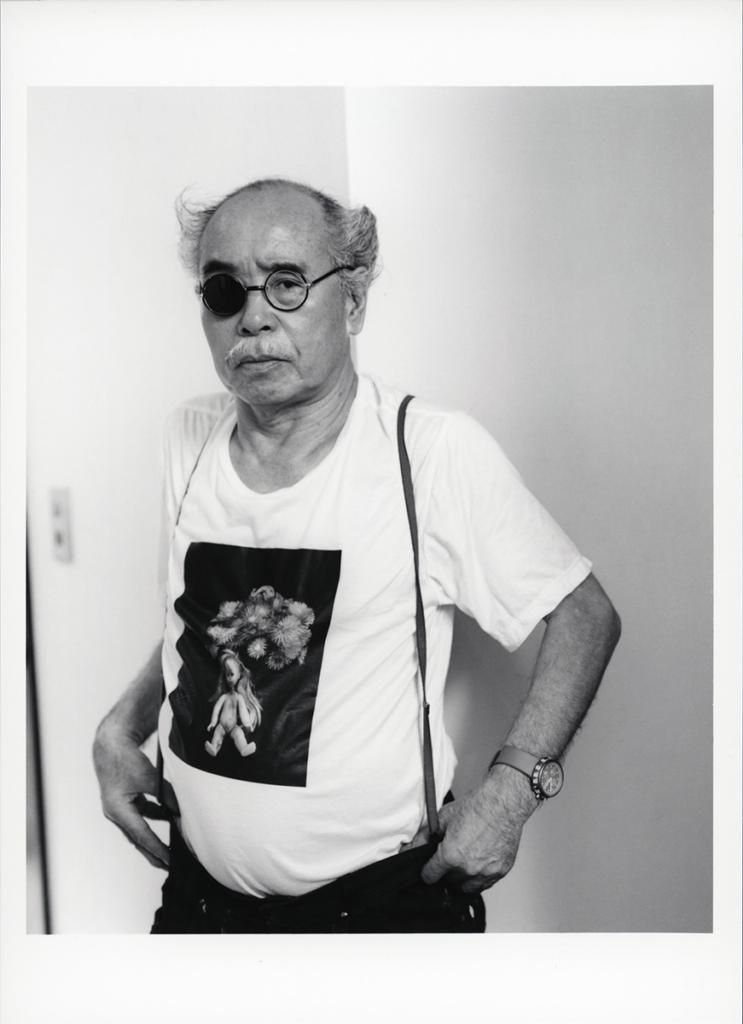

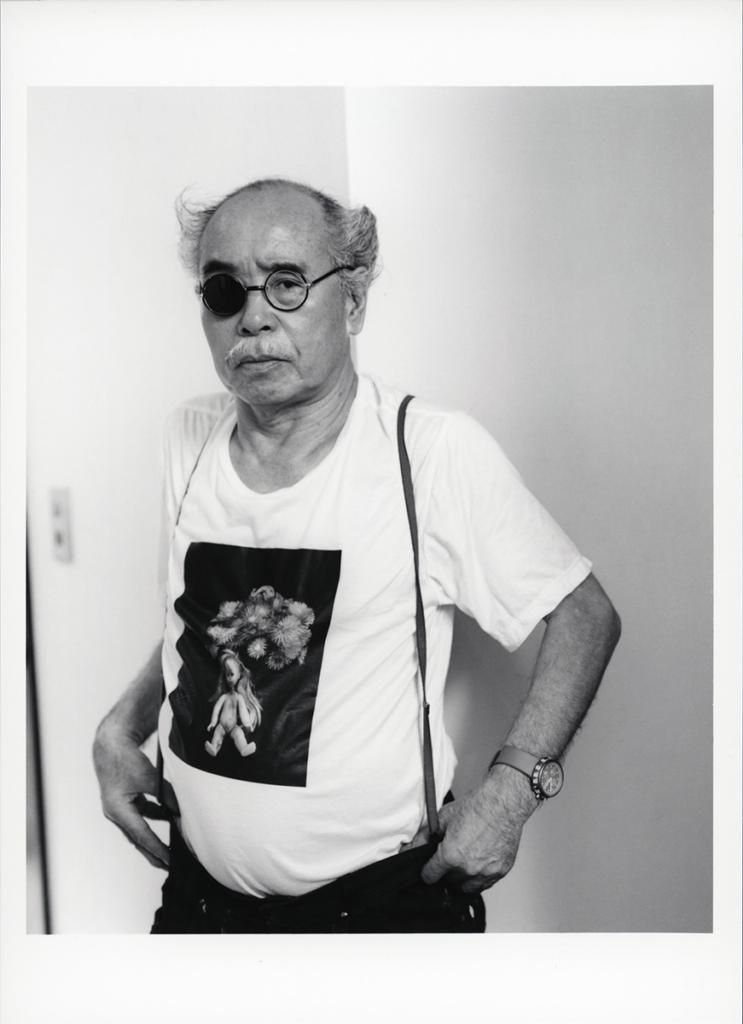

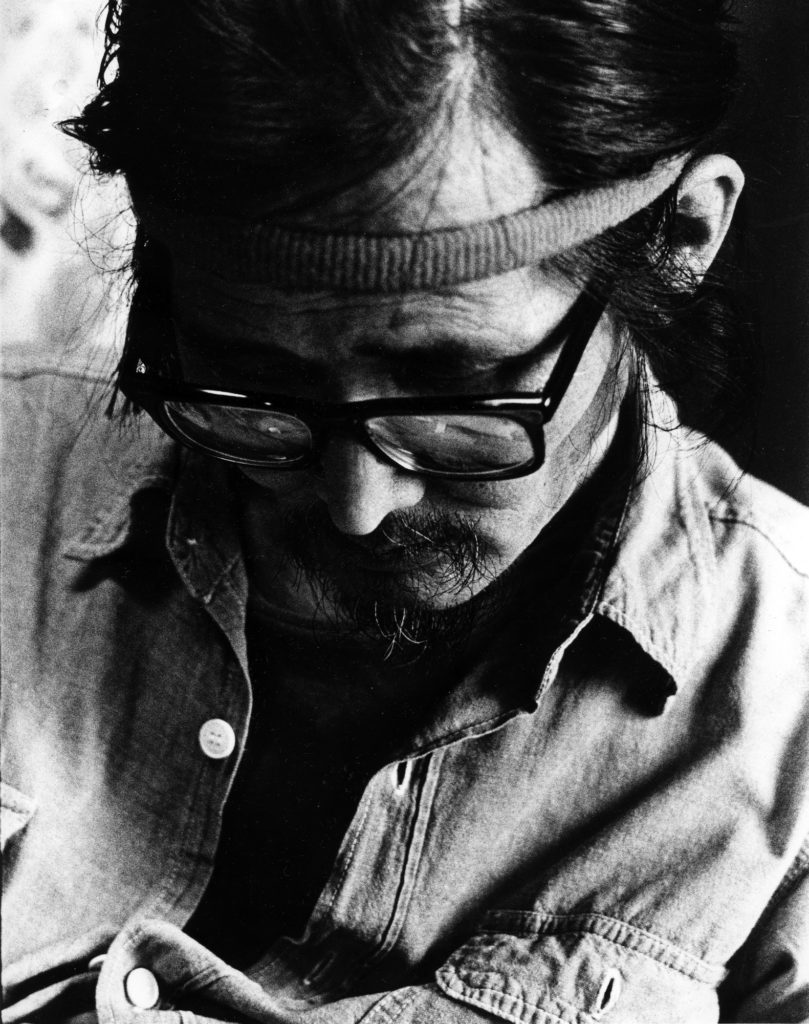

Nobuyoshi Araki

1940, Tokyo, Tokyo prefecture

One of the most prolific figures in the field of Japanese photography, Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940) has produced countless pictures and more than five hundred photobooks since 1970. Such an abundant body of work defies easy categorization, an endeavor made all the more challenging by Araki’s experimentation with media including collage, film, and, more recently, Polaroid instant technology. Araki’s wry, irreverent work, frequently employing sexual subject matter, has often ignited controversy and earned him a degree of notoriety. The frenetic nature of his photographs, which he tends to shoot with very little preparation, is emblematic of the Japanese experience of World War II and its chaotic aftermath.

Araki entered Chiba University in 1959, majoring in photography and film. The regimented and technical nature of the program, then situated in the engineering department, was unappealing to the nonconforming Araki. The film he turned in as his final project, however—Children in Apartment Blocks (1963)—served as the germ for one of his earliest photographic series, for which he received an award from Taiyo magazine the following year. Satchin (1964) focuses on schoolchildren in the Shitamachi neighborhood of Tokyo, which remained largely unchanged amid the flurry of rapid urban transformation leading up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. After graduation, Araki took a job as a commercial photographer for the advertising firm Dentsu. While he found the work frustratingly dull, he made good use of Dentsu’s well-stocked facilities to pursue photography on his own time, going so far as to illicitly use the company’s photocopier to produce an early photobook.

Two events pivotal to Araki’s life and work took place in the late 1960s: his father died in 1967, and he met his future wife, Yoko Aoki, then working as a typist at Dentsu, the following year. Death and love would become two of the principal driving forces behind Araki’s profoundly human photography, and Yoko would become Araki’s most frequent photographic subject. The couple wed in 1971 and embarked on a honeymoon, which Araki extensively photographed. With its narrative style, personal tone, and vernacular aesthetic, the resulting volume—Sentimental Journey (1971)—is regarded as one of the most important Japanese photobooks of the twentieth century. Araki’s growing success as a photographer allowed him to leave Dentsu to focus solely on his artistic career in 1972.

Araki has referred to his wide-ranging and eclectic work as “I-photography,” after the “I-novel,” a Japanese confessional literary genre often written in the first person. His unwavering concentration on his own life and experiences—sexual and otherwise—pushed against the dominant documentary photographic aesthetic, epitomized by such figures as Hiroshi Hamaya, as well as the are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) aesthetic of the Provoke movement, prevalent in Japanese avant-garde photography beginning in the late 1960s. Araki tackled these approaches head-on in his series Pseudo-Reportage. The related photobook, published in 1980, pairs these quasi-documentary pictures with misleading captions, underscoring the problematic nature of photographic veracity.

After Yoko passed away, in 1990, Araki began a host of new projects, even using his own diagnosis with prostate cancer in 2008 as a jumping-off point to explore the diminishing status of analog photography. 2THESKY, my Ender (2009) consists of photographs covered with salt, which will cause the object to deteriorate over time, mirroring the physical decline of the photographer himself. While he was not included in the landmark exhibition New Japanese Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974, organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, he was included in Yamagishi’s second exhibition collaboration in the United States, Japan: A Self-Portrait at the International Center of Photography in New York in 1979. Araki gained international exposure in Europe prior to this, participating in Neue Fotografie aus Japan at the Kulturhaus der Stadt, Graz, Austria, his first group show outside Japan, in 1977. His first international solo show took place in 1992: Akt-Tokyo: Nobuyoshi Araki 1971–1991 at the Forum Stadtpark, Graz.

— Matthew Kluk

-

Naoya Hatakeyama

1958, Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture

Naoya Hatakeyama (b. 1958) examines the meaning of landscape in the present day, when all land is affected by human activity. He maintains that even landscapes we admire for their untouched beauty, such as the craggy mountaintops of the Alps, have been altered by human use—by their portrayal as idealized Nature—and we must recognize this as the current condition of the world. Thus his work embodies an acceptance of human participation in nature.[1]

Hatakeyama was born in northern Japan and studied art at the University of Tsukuba. He admired the countryside and the natural beauty of the mountains in his home region. In 1983 , when he had his first exhibition in Tokyo, at Zeit-Foto Salon, he showed a group of black-and-white pictures of the traces humans had made in that still relatively open land: a modest lighthouse, plowed fields, shadows cast on a newly paved road. He moved to Tokyo the following year, and this brought the relationship of the countryside to the city into active dialogue in his work. He also began working in color, a practice he continues today.

Hatakeyama’s first major project was Lime Hills (1986–90), in which he photographed limestone quarries throughout Japan. Finding the peaceful contemplation of these places to be incomplete, he soon documented the detonations the engineers devised to loosen the rock and represented the choreographed explosions sequentially, in the series Blast (1995–2008). “When I learned that Japan was a land of limestone,” Hatakeyama has said, “my appreciation of its cityscapes underwent a subtle change.” The country’s abundant supply of the stone is used to make cement and as aggregate for concrete, among other things. “In the texture of concrete I can feel the trace of corals and fusulinas that inhabited warm equatorial seas 200 to 400 million years ago.”[2] Flying over Tokyo, he was reminded of the quarries: “The uneven white scene spreading endlessly was not the limestone I had seen in the mine, but the buildings of the city of Tokyo. It suddenly appeared to me that the minerals in the huge emptiness had not simply disappeared but were carried all the way here to be transformed and exist right in front of me.”[3]

In his series Untitled (1989–2005), Hatakeyama photographed the city from distant vantage points. The resulting pictures, shown either individually or arranged in a grid, look like geological sections. This initiated an intense focus on Japan’s urban structures. The River series (1993–94) pairs Tokyo’s built structures with the often luminous and mysterious waters on which the buildings are constructed. In Underground (1998–99), he followed the city’s sewers below its surface, carrying in lights to see what was hidden there. He also made pictures of buildings at night, presenting them backlit, in light boxes, so that the structures appear to emit their own magical illumination (Maquettes/Light, 1995–97). Untitled, Osaka (1998–99) comprises side-by-side views of a temporary model-home show and its subsequent demolition. Hatakeyama finds a particular beauty in these urban subjects, which he presents objectively and without judgment.

He has also examined the dialogue between nature and culture in Europe in both the past and the present. His series Ciel Tombé (2006–8) depicts tunnels in northern Paris, created over centuries by the quarrying of stone for construction of the city and now destabilized and decaying; in a related photograph (1991, printed 2011) the same area is seen from above. He has photographed the dismantling of mining operations in Northern Europe, including areas now designated UNESCO World Heritage sites to memorialize the industry that once sustained local communities, in the series Zeche Westfalen I/II Ahlen (2003–4). Other pictures by Hatakeyama show the apparently natural beauty of slag heaps, like perfectly shaped mountains (Terrils, 2009–10).

Hatakeyama’s focus was altered by the devastating 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, a tragic moment for the nation and personally for the photographer, whose hometown was almost completely demolished and who suffered terrible loss. Since then he has studied not only the devastation caused by the disaster, but also the experience of returning to the affected region many times in the years since and witnessing the radical changes taking place. It has provoked him to rethink his work, particularly the separation of his own private or personal photography from his work as an artist. His Rikuzentakata series (2011) brings together personal photographs made in the past with pictures of the stages of reconstruction.[4] Finally, Hatakeyama has examined the stance of observation itself. CAMERA (1995–2009) is a series of photographs made in hotel rooms at night, accumulated during Hatakeyama’s travels over several years. They show what the photographer sees from his hotel bed, lit by reading lamps; they describe only the lighted interiors (camera is Italian for room). Comprising a meditation on the very nature of photography, these pictures emphasize the internal, cognitive, and analytic nature of the medium, detached even as it is involved in examining the world outside.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

See the artist’s talk presented at the Izu Photo Museum, Nagaizumi, Japan, January 2013.

Naoya Hatakeyama, Lime Works (Tokyo: Synergy Kikagaku, 1996), 54. See the artist’s talk presented at PhotoAlliance, San Francisco, September 2006.

Naoya Hatakeyama quoted in Stephan Berg, “Down to the Water Line,” in Naoya Hatakeyama, ed. Stephan Berg (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2002), 12.

See the artist’s talk presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, April 2015.

-

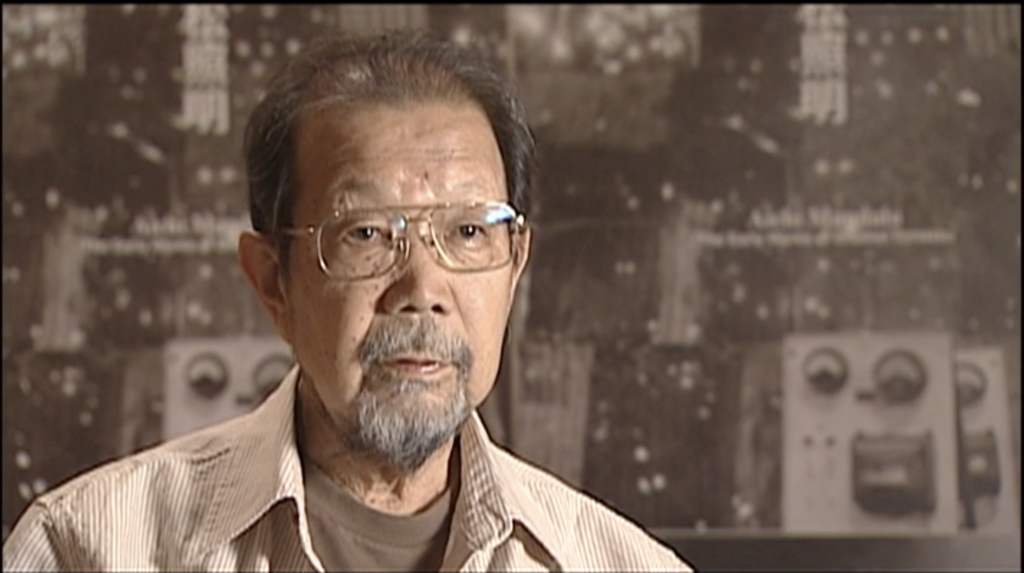

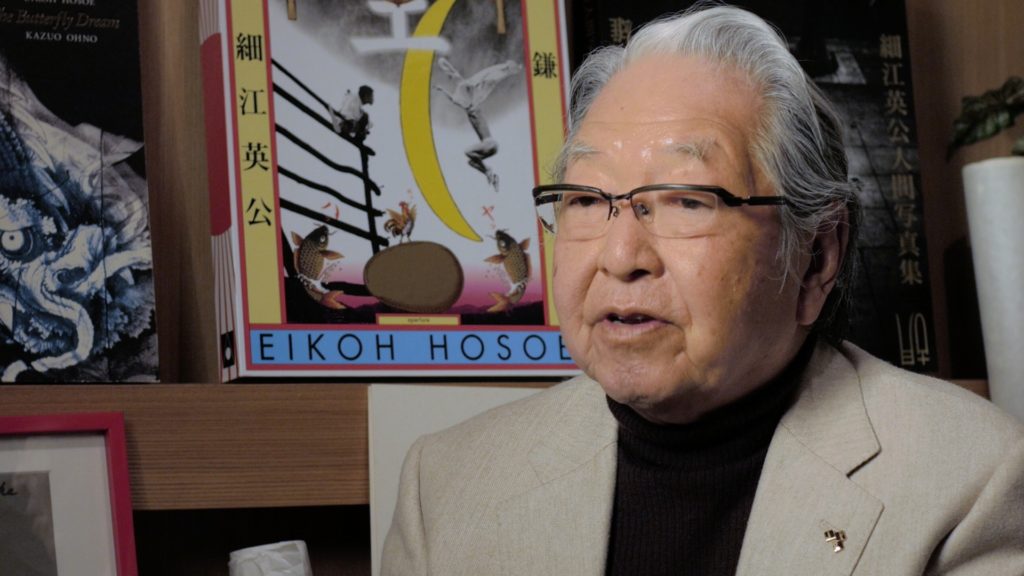

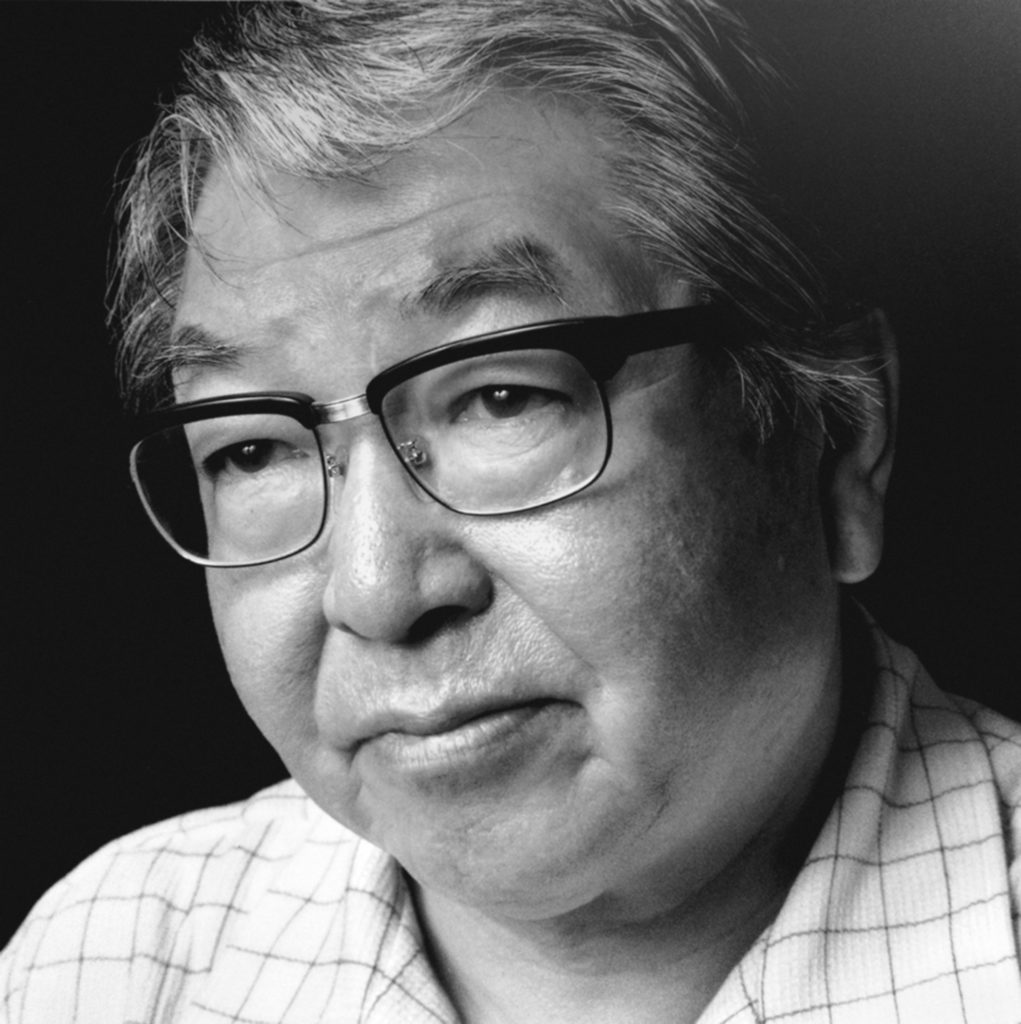

Eikoh Hosoe

1933, Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture

The principal work of Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933) engages directly with the vibrant, dynamic culture of postwar Japan. As the country emerged from poverty and formed an ambiguous relationship with the United States, people embraced radical rejections of convention such as those described in Yukio Mishima’s novel Forbidden Colors. Published in two parts, in 1951 and 1953, the book portrays the subversive and liberating gay society that flourished in Tokyo during this period, and it inspired a generation of avant-garde art makers in Japan. Hosoe is most frequently associated with an extended portrait series of Mishima himself, made at the writer’s invitation. The sequences of mannered pictures focusing on the author’s beautifully cultivated, semi-nude body have been considered Hosoe’s major contribution since they first appeared in book form in 1963, under the title Killed by Roses. Set against odd, hand-painted elements from Italian Renaissance paintings such as Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (ca. 1485), the deeply provocative portraits of Mishima in his lavish, neo-rococo home were manipulated with high contrast and often excessive grain. Theatrical, idiosyncratic, and powerful, the photographs remain unique to the medium. The series was revised with Mishima’s participation and renamed Ordeal by Roses at his request in 1970, just before his spectacular public suicide.

Hosoe’s early work also centered on dance—particularly butoh, an iconoclastic, antimodernist form developed by Tatsumi Hijikata in the 1960s. Imbued with a fierce psychological edge, these pictures highlight details of the dancers’ bodies in intimate yet theatrical settings, emphasizing differences in gender, age, and skin color. Perhaps his most distinctive series, and one free of obvious staging, is Kamaitachi, published in 1969. He created these works with Hijikata in northern Japan, where both were born before World War II. Hosoe photographed Hijikata as an embodied demon-spirit, neither evil nor beneficent—a “sickle-toothed weasel” who engages playfully in the outdoors, interrupting local farmers at work and dramatically and fiendishly abducting a woman, haunting children, and sprinting across gleaming rice fields with a baby. These strange encounters seem to reflect a dark, primordial Japan, as well as the tensions and anxieties of the period in which they were made. A lesser-known series, Simmon: A Private Landscape, produced in the 1970s but not published until 2012, follows a prominent cross-dresser who inhabits Tokyo in much the same way the spirit-Hijikata haunted the northern countryside. These pictures constitute some of Hosoe’s most original work.

Hosoe has devoted much of his career to fostering photography as an art form of supreme possibility. In 1959 he cofounded VIVO, a loose association of photographers that included Shomei Tomatsu, Kikuji Kawada, Ikko Narahara, and other important innovators in the medium. But perhaps his most singular gift to the development of photography in his country was the early network of ties he forged with photography communities abroad. Hosoe has had a relationship with American photography since the 1960s that is more intimate than that of any of his contemporaries. As a schoolboy making pictures in his father’s darkroom, he also studied English, and his first works were indebted to the style of Life magazine—one early project was a fictional photo-essay, An American Girl in Tokyo (1956), complete with captions. Life was easily available at the American Cultural Center in Tokyo, where Hosoe remembers seeing an exhibition of work by Edward Weston in 1953. His fluent English permitted him to develop relationships that would not have been possible otherwise: he first traveled to the United States in 1964 and met Nathan Lyons at the George Eastman House (now the George Eastman Museum), Rochester, New York. During subsequent visits Hosoe arranged for the museum to create a comprehensive exhibition of the history of photography drawn from its collection, Great Photographers of the World: Masterpieces from the George Eastman House Collection (1968), which toured Japan. By the following decade he was teaching workshops everywhere from France to Yosemite—often with American photographers such as Ansel Adams, Jack Welpott, and Judy Dater—and meeting significant figures in other media, such as the Spanish painter and sculptor Joan Miró. He continues to be an important teacher in Japan and has served as director of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Hokuto, since it opened in 1995, furthering his effort to support the photography of the next generation.

— Sandra S. Phillips

-

Miyako Ishiuchi

1947, Kiryu, Gunma Prefecture

Raised in Yokosuka, home to the largest American naval base in Japan at that time, Miyako Ishiuchi (b. 1947) was taught while she was growing up to fear the city’s American section, especially the bar district where soldiers fraternized with Japanese women. Reports of violence there were frequent. She left Yokosuka as soon as she could–in 1966–to study design at the prestigious Tama Art University in Tokyo. There she participated in student protests that closed down the school for almost a year in 1969, part of a wave of student demonstrations across Japan, demanding university administration reform and fighting American influence in the region. She was also involved in the burgeoning women’s movement and formed a women’s group with two fellow students.

Ishiuchi initially worked in textiles, but by 1975 she was actively making photographs. She found her essential subject by confronting her past: in 1976 she returned to Yokosuka to photograph its American military population, then in decline with the end of the Vietnam War. The pictures she made there were, she said, “coughed up like black phlegm onto hundreds of stark white developing papers.”[1] Persuading her father to give her funds he had set aside for her dowry, she published a group of these photographs in her first book, Apartment, in 1978. Two more books of her Yokusuka pictures followed: Yokosuka Story (1979) and Endless Night (1981). In the latter, she focused on the crumbling bars and brothels that had so distressed her, now abandoned and being demolished. To firmly acknowledge the centrality of Yokosuka’s heritage for her, in 1981 she rented a cabaret in the city to hold an exhibition of this work. She later commented: “The photograph exhibit took place, as though in revenge, there in Yokosuka which was in America, in America which was in Yokosuka, a town which thrived from what two wars yielded, on a street now become a pathetic sight to see.”[2] She would stop photographing Yokosuka in 1990.

Ishiuchi’s unique perspective on the American presence in Japan—reflected in distinctively quiet but also emotionally riven photographs—drew the attention of Shoji Yamagishi, renowned editor of the journal Camera Mainichi. Ishiuchi was the only woman whose work he included in Japan: A Self-Portrait, the 1979 exhibition he organized for the International Center of Photography in New York. Thus introduced internationally, Ishiuchi’s particular vision drew the attention of other Japanese women photographers, especially Asako Narahashi, with whom she would later create the photographic magazine Main (1996–2000). In 1984 Kyoko Yamagishi, widow of Shoji Yamagishi, invited her to participate in a project with a large-format Polaroid camera. She used the occasion to photograph members of her high-school class of twenty years earlier, in the series Classmates (1984). This experience encouraged her to expand her subject matter in a radically new direction. Rather than photographing the place of trauma, which was Yokosuka for her, she photographed its effects, first on the body and later on its second skin, clothing. The project 1∙9∙4∙7, begun in 1987 and published in book form in 1990, involved the close-up examination of the hands and feet of women born, like her, in 1947. Carefully detailing what the bodies of women her age—neither young nor yet old—looked like, she identified her subjects only by birth year and profession. This intensified concentration on the body’s surface led Ishiuchi to her subsequent series, Scars (1991–2003). She has likened these marks on the human body to photographs themselves: “When I first encountered the scar, I reflected on photography. . . . While a person hopes to remain unblemished through life, all must sustain and live with wounds, visible and invisible . . . an imprint of the past, welded onto a part of the body.”[3]

By 1999 Ishiuchi began to photograph her mother, concentrating on her scars and other details of her aged body. This series of pictures would continue after her mother’s sudden death the next year, when Ishiuchi turned to her mother’s clothing and other personal effects, producing monumental pictures of items such as used lipsticks and worn undergarments, rendered like cobwebs with wear. Mother’s was presented in the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2005. More recently Ishiuchi has photographed clothing found after the atomic bomb explosion at Hiroshima, spreading the garments on light boxes to suggest the personality of the wearer. Clearly used and often handmade, the clothing items embody their traumatic history but are photographed in a way that expresses a specific personality, even a spiritual presence.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

Miyako Ishiuchi, Yokosuka Story (Tokyo: Shashin Tsushinsha, 1979); quoted in Amanda Maddox, “Against the Grain: Ishiuchi Miyako and the Yokosuka Trilogy,” in Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015), 23.

Miyako Ishiuchi, Yokosuka Again, 1980–1990 (Tokyo: Sokyu-sha & Mole, 1998); quoted in Maddox, “Against the Grain,” 28.

Miyako Ishiuchi, Scars (Tokyo: Sokyu-sha, 2005), n.p.

-

Rinko Kawauchi

1972, Higashiomi, Shiga Prefecture

In contrast to photographers working in the dark and frenetic style developed during the Provoke era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Rinko Kawauchi (b. 1972) has pursued a more restrained and lyrical aesthetic over more than two decades. The most quotidian objects and occurrences are transformed through her lens into sublime images that frequently highlight the ephemeral, fragile, and even sinister nature of everyday life.

Kawauchi studied graphic design and photography at Seian University of Art and Design, Otsu, Japan, and worked in the commercial and advertising realms upon graduating in 1993. She shifted her focus to fine art a few years later and quickly gained international recognition—including the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award—after the simultaneous release of a trilogy of photobooks in 2001: Utatane, Hanabi, and Hanako. Almost entirely devoid of text, these volumes rely on the power of the images speaking to one another across the pages to create their narratives. Common scenes such as a curtain blowing out an open window, soap bubbles gathering in a sink drain, or a young child jumping rope seem to reflect a deeply personal and idiosyncratic experience of the world, as well as a dedicated practice of intense looking. The muted color palette in Utatane, which has become the artist’s trademark, produces a dreamy and ethereal atmosphere that complements her sparse and mysterious compositions. Similarly, Kawauchi renders the explosive fireworks in Hanabi as quasi-abstract studies that are seemingly more concerned with the effects of light than with figuration.

Kawauchi’s poetic imagery has continued to develop in subsequent series. While the eyes, the ears (2005) comprises the same types of quiet photographs found in her earlier bodies of work, it juxtaposes the pictures with short—though equally obscure—verses of the artist’s own invention. Her 2013 project Ametsuchi ventures even further into the metaphysical realm. Focusing on a landscape Kawauchi first encountered in a dream, it captures the centuries-old process of noyaki, a yearly controlled burn of Japan’s Aso countryside in order to maintain and refresh the grasslands for grazing animals. Though the ultimate outcome of the procedure is regeneration, Kawauchi’s photographs of the hills ablaze are decidedly melancholic. Ametsuchi may seem like a departure from the tranquility of Utatane, but both reveal an enduring interest in what the artist calls “the flow and cycle of human practices.”[1]

— Matthew Kluk

Notes

Rinko Kawauchi, in “Rinko Kawauchi Contemplates the Small Mysteries of Life,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, March 2016, video, https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/rinko-kawauchi-contemplates-small-mysteries-life/.

-

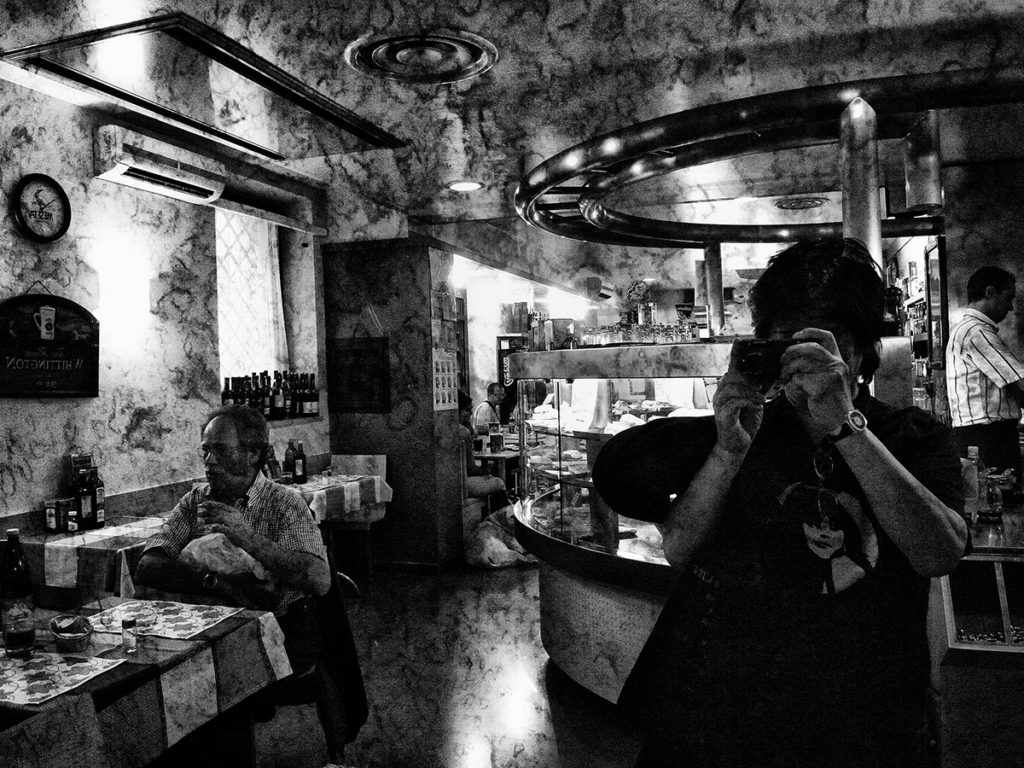

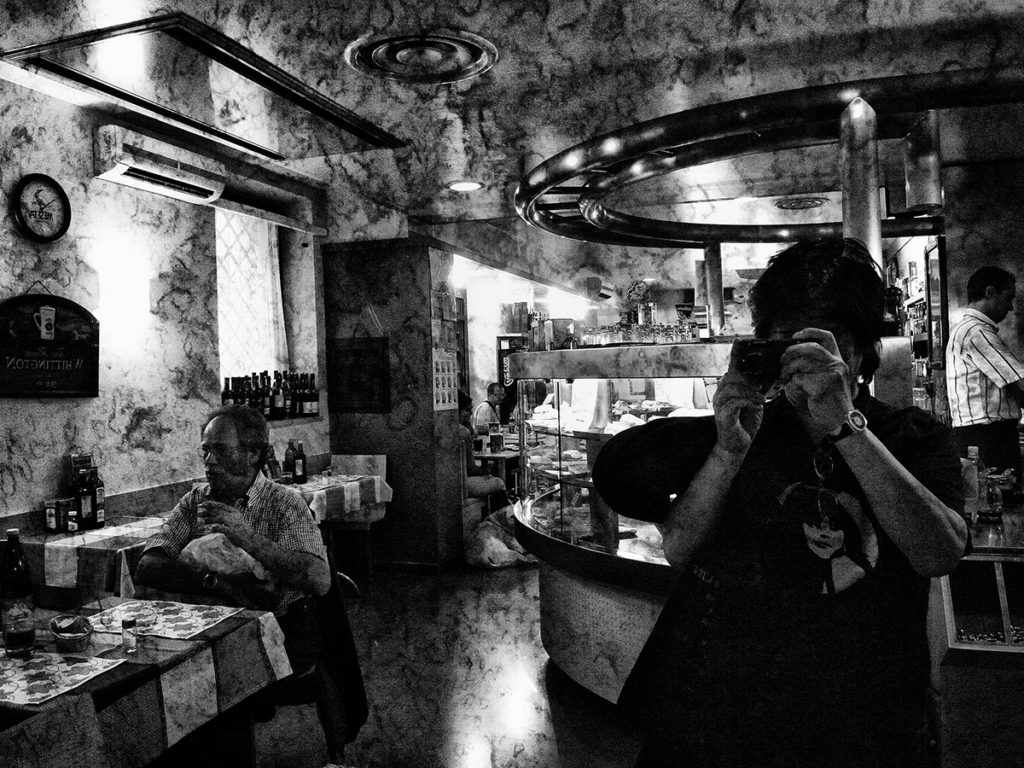

Keizo Kitajima

1954, Suzaka, Nagano Prefecture

While the photography magazine Provoke ran only three issues, between 1968 and 1969, it had a significant impact on subsequent generations of photographers. Keizo Kitajima (b. 1954) was one of the first and most prominent artists to incorporate its are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) style and its ideals of subjectivity and anti-commercialism into his work.

In 1975 Kitajima took a class taught by Daido Moriyama at Workshop Photo School, a photography school founded by several members of the Provoke circle after the magazine ceased production. The class proved foundational, and Moriyama became a lifelong mentor. Just one year later the pair established Image Shop Camp in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo—one of a number of artist-run galleries popping up at the time that served simultaneously as exhibition spaces, darkrooms, and meeting places for like-minded photographers. From January through December 1979 Kitajima presented a monthly series of exhibitions of experimental photographs that he took around Tokyo, accompanied by booklets titled Photo Express: Tokyo. These pictures adopt the are-bure-boke aesthetic of Provoke, but the way the artist figured Japan’s booming consumer culture was distinctly his own: pulling in close to his subjects, he foregrounded their jubilant humanity and injected each scene with a pulsating, ecstatic energy.

With Moriyama’s encouragement, Kitajima began to expand his practice beyond Tokyo. Having previously found inspiration in Shinjuku’s sordid and vibrant nightlife, in 1980 he turned his attention to the red-light district of Koza, a city in Okinawa Prefecture. The United States had established an air base at Kadena, also in Okinawa, at the end of World War II, and in 1970 Koza had been the site of a violent protest against the ongoing American military presence. Kitajima’s photographs in Photo Mail from Okinawa capture the wild and tense interplay of sex, money, and cultures that continued to mark the interactions between Japanese citizens and American soldiers ten years later. His work also took him to New York, where he photographed the height of 1980s decadence and excess both in black and white and in color. Not inhibited by his outsider status, Kitajima came right up to his subjects in the city streets, as he had in Tokyo. This direct engagement is often evident in the pictures, which were published in 1982 to great acclaim: New York earned Kitajima the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award, and it was even adapted for a 1995 Comme des Garçons fashion advertisement campaign.

In 1990 Asahi Shimbun newspaper, which founded the Kimura Ihei Award, commissioned Kitajima to travel throughout the Soviet Union to photograph the multiplicity of people and places across its numerous republics. The artist created an extensive visual document of the USSR on the brink of change—the state was officially dissolved on December 26, 1991, just one month after he finished shooting. This fortuitous timing lends considerable historical gravitas to the series, USSR 1991, and has greatly influenced the way the photographs have been interpreted. Often visibly exhausted, several of the pictured individuals clutch relics of earlier cultural and national identities, foreshadowing the seemingly inevitable fragmentation of the state. While Kitajima’s landscapes depict a utopian ideal in clear decline, his sympathetic portraits capture a resilient and diverse population.

Today Kitajima remains an active and prolific member of Japan’s photographic community. He has largely transitioned from street to studio photography and has been working on an extensive, ongoing series of portraits of men and women and their built environments that has been exhibited frequently over the past twenty years. His interest in supporting younger photographers has also persisted: in 2001 he founded photographers’ gallery, a hybrid artists’ cooperative, exhibition space, and publishing house in Shinjuku.

— Matthew Kluk

-

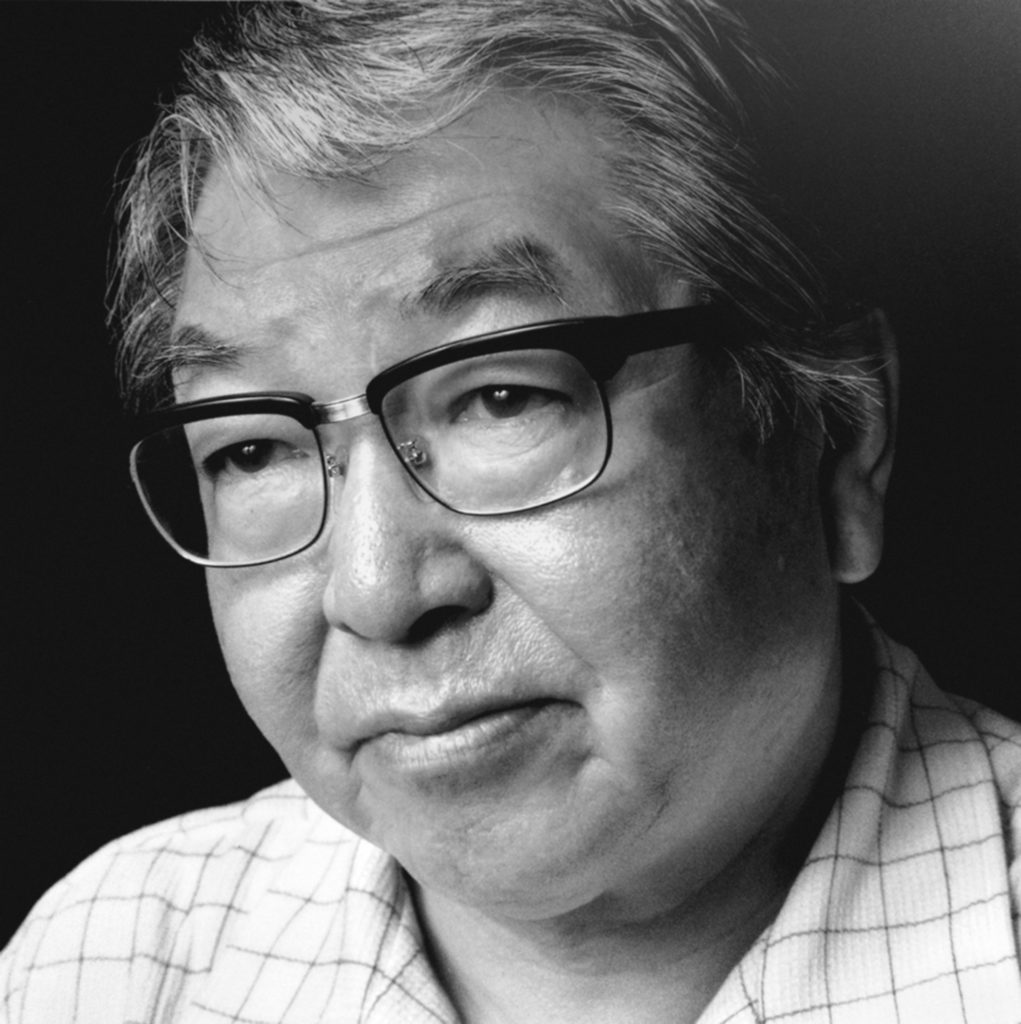

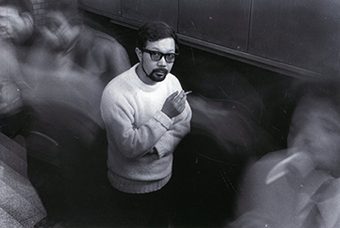

Daido Moriyama

1938, Ikeda, Osaka

A seminal photographer of lyrical, expressionist sensibility, Daido Moriyama (b. 1938) has restlessly portrayed the emotional condition of everyday postwar Japan. He belongs to the generation who matured in the decades following Japan’s surrender—who lived in urban centers and experienced the country’s submission to occupation and political pressures by its “liberators,” as well as its emergence as a vibrant economy. These and other factors stimulated a period of radical art-making. “Chaotic everyday existence is what I think Japan is all about,” he has said. “This kind of theatricality is not just a metaphor but is also, I think, our actual reality.”[1] Moriyama worked as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe while the older photographer made his portrait series of the novelist Yukio Mishima, pictures of theatrical sexuality. Later he saw work by William Klein and Andy Warhol, whose photographs, provocative and raw, exposed a society of vibrant estrangement in New York. Moriyama responded most of all to the vitality and fleshy dissipations he observed at the American bases near where he lived, in Zushi, then teeming with American servicemen fighting the Vietnam War. He was attracted to the culture there: to the jazz music, to the honky-tonk joints and the heterogeneity of their clientele, and to the exuberance of the soldiers. The nonpolitical Moriyama found in the rich complexities and dark ambiguities of the times his special subject.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Moriyama contributed regularly to camera magazines published for the amateur, especially the important Camera Mainichi, producing pictures for these publications that were essentially poetic rather than journalistic. His subjects included popular entertainment and the experimental theater of Shuji Terayama, as found in the pictures of his first book, Japan: A Photo Theater (1968). An admirer of Jack Kerouac, he hitchhiked throughout Japan or found drivers willing to take him on the new highways at all hours of the day and night, stopping at deserted cafes and photographing through car windows, inspired by Kerouac’s On the Road. These photographs were published serially in Camera Mainichi beginning in 1968, but he would continue this restless movement around the country as well as in city streets in the decades that followed. Through an introduction from his friend Takuma Nakahira, Moriyama participated in the experimental magazine Provoke (1968–69), maintaining his apolitical stance within this highly political group. Experimenting boldly with cropping and pronounced grain, he also took pictures of pictures and reframed them, as in the Warholian series Accident (1969), a group of which are based on a traffic safety poster. In 1974 he produced a book of Xeroxed photographs of a 1971 visit to New York, calling it Another Country in New York, after another favorite author, James Baldwin.

Moriyama’s work is best understood in the context of the deeply divided politics of the times, especially the protests surrounding the renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in 1970, as well as the subsequent decline in political antagonism between the two countries and the rise in consumerism. For Moriyama, this was the beginning of both a highly productive period and, by the mid-1970s, a time of personal instability. In 1972 he published two important books, Hunter and Farewell Photography, and launched the small photographic magazine Record. Hunter contains some of Moriyama’s best-known pictures, printed in stark, gripping contrast. Farewell Photography is a gorgeously experimental production that continued his interest in Warhol-inspired printing; many of the pictures are blurred and highly cropped, and their subjects, from a blank television screen to a looming helicopter suspended in midair, are often almost unrecognizable. The mood is tragic and nihilistic. Appropriately, the book’s introduction is a conversation with his friend Nakahira, who would suffer a severe case of alcohol poisoning soon after.

It took some years for Moriyama to evolve out of this intensity. He began to visit the Japanese countryside, where he produced The Tales of Tono (1974, published 1976), a strange and disorienting series of pictures that reach into preindustrial rural Japan but are not escapist. That year he began to receive attention outside Japan: his work was included in New Japanese Photography, the 1974 exhibition organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which traveled to SFMOMA the following year. This success coincided with the recognition of photography as a particular form of artistic expression in Japan, celebrated in the exhibition Fifteen Photographers Today at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Moriyama has continued to work experimentally and to rethink his earlier projects, often incorporating older work with more recent pictures in expanded book formats. The photographs in Light and Shadow (1982), produced after a long period of inactivity, are imbued with a new, even blinding clarity. In 1990 he published Lettre à St. Loup, in which he describes the first photograph, made by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce in 1827, as deeply important to him; Niépce’s photograph is a grainy, confusing, yet eloquent picture of the passage of the sun from one side of a courtyard to the other.[2] More recently Moriyama has taken up color again, which he employed infrequently in the 1970s. These new color pictures, made with a special camera, have injected a directness, even a sense of normalcy, in contradistinction to the rawer work of the earlier years.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Daido Moriyama Stray Dog

Notes

Daido Moriyama, letter to Sandra S. Phillips, n.d. [1998]; quoted in Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1999), 32.

Daido Moriyama, “That Summer Day in St. Loup,” in Lettre à St. Loup (Tokyo: Kwade Shobo Shinsha, 1990), n.p.

-

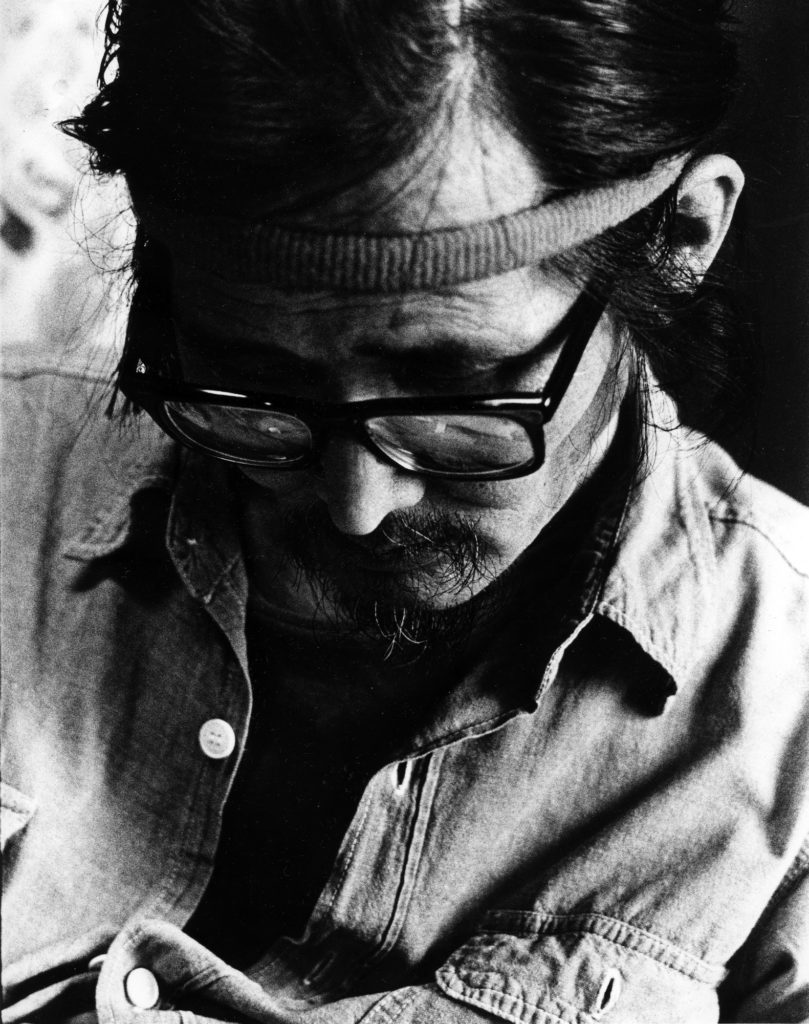

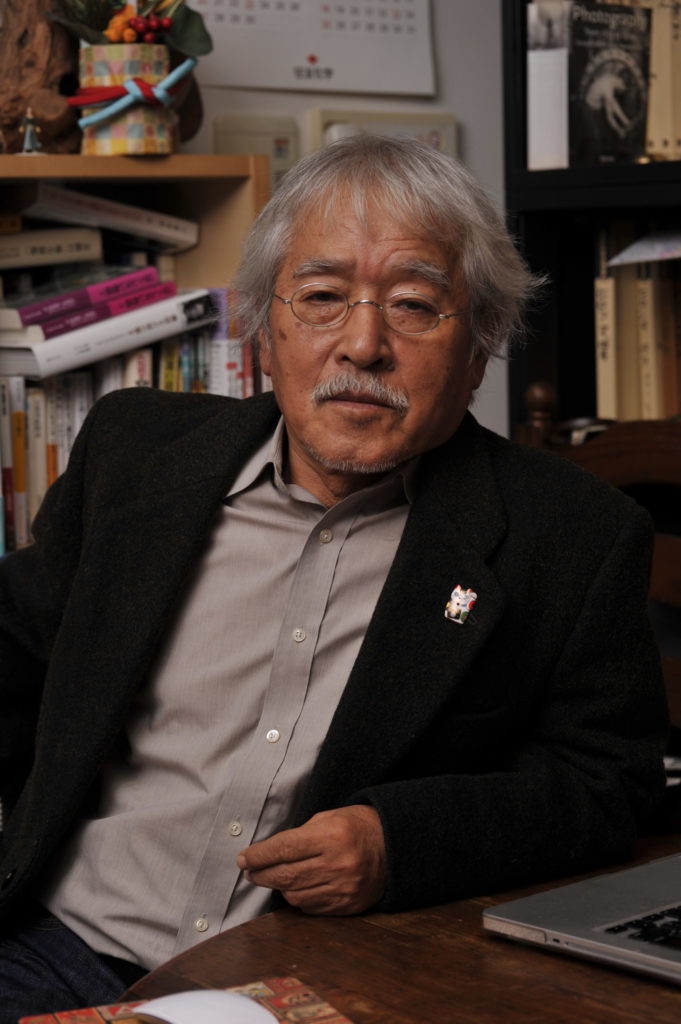

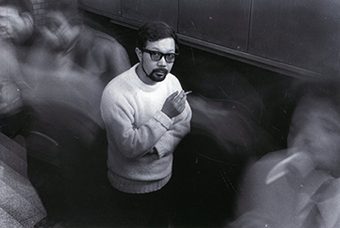

Takuma Nakahira

1938, Shibuya, Tokyo

2015, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture

Takuma Nakahira (1938–2015) was a radical and critical leader of modern photography, pushing it to its limits. Yet, after losing his speech and his memory toward the end of his life, he can also be said to have returned to the point of origin, or “degree zero,” of the medium.

Nakahira graduated from Tokyo University of Foreign Studies with a degree in Spanish in 1963. After holding a number of different jobs he became an editor for the New Left journal Contemporary View, where he published photographs by Shomei Tomatsu. Tomatsu roused Nakahira’s interest in the medium and invited him to join the editorial board for the seminal 1968 exhibition A Century of Japanese Photography, organized by the Japan Professional Photographers Society. Nakahira struggled to choose between careers in photography or poetry, but the works he discovered while conducting research for the show convinced him to focus on making pictures. The exhibition also led to his collaboration with fellow editor Koji Taki on the independent journal Provoke. With A Century of Japanese Photography, Nakahira and Taki gained an understanding of the language of Japanese photography of the past; with Provoke, they rejected that language and pushed their photography in a more experimental direction. Daido Moriyama became a member of the group associated with the magazine beginning with the second issue, upon Nakahira’s invitation. Though Nakahira and Moriyama’s emphasis on monochrome, on rough grain, and on slanted compositions was ridiculed as bure-boke shashin (blurry, out-of-focus photography), they maintained that in a world in constant flux, their manner of taking pictures best reflected what could be perceived by the naked eye.

After the third issue of Provoke, the group published the book First Abandon the World of Pseudo-Certainty (1970) and discontinued the journal. Nakahira felt that the bure-boke style—meant as a direct rebuttal of conventional aesthetics—was about to gain acceptance and was therefore losing its innovative potential. He had already begun to participate in international exhibitions such as the 1969 Paris Biennale, where he made a series of six bleak photogravure cityscapes titled La nuit (Night, ca. 1969). He also published the first anthology of his own work, For a Language to Come (1970), which captured his distinctive poetic sensibility and the radical criticism of photography being made by photographers themselves. In 1971 he was invited to the Paris Biennale by Takahiko Okada, the commissioner for Japanese entries and a former Provoke member. Nakahira presented his experimental project Circulation: Date, Place, Events, for which he wandered around Paris and photographed anything that caught his eye, adding the resulting prints to the exhibition space each day.

Nakahira became critical of his efforts in the 1973 essay “Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?,” in which he dismissed his former desire to “shape the world according to his own ideas.” He repudiated the ambiguity of shadow and emotion, advocating instead for juxtapositions of sharp color photographs much like the illustrations in botanical dictionaries. This stance eventually led him to burn many of his prints and negatives. Eager to distance himself from the bure-boke shashin he had helped create and that had been widely adopted even in the commercial realm, Nakahira suffered a creative crisis. His artistic output dwindled, but he continued to write.

In 1973 Nakahira also traveled to Okinawa for the first time, to investigate the case of a young man accused of murdering a police officer during a recent general strike. This experience stirred a lasting interest in the region. From 1974 to 1977 Nakahira journeyed north through the Okinawa island group, probing the cultural demarcation between the Japanese mainland and these southernmost reaches. The resulting series Amami: Waves, Graves, Flowers and Sun (1976) and On the Border: The Tokara Islands, Depopulated (1977) appeared in the journal Asahi Camera and were intended in part as critical responses to Tomatsu’s The Pencil of the Sun: Okinawa, Sea, Sky, Island, People, and Then toward Southeast Asia (1975), which sought to expose a supposed common cultural foundation among the countries of the Pacific Rim.

In 1977 A Duel of Photo-Theory was published, with photographs by Kishin Shinoyama and text by Nakahira. That year, at a party at his home, Nakahira collapsed with acute alcohol poisoning. He survived, but the incident left his speech and memory permanently damaged. After a partial recovery, he spent most of his time making photographs. He published A New Gaze in 1983 and Adieu à X in 1989. Color works would be printed in later books such as Hysteric Six: Nakahira Takuma (2002), Documentary (2011), and the posthumous Okinawa (2017).

The first decade of the twenty-first century was a period of growing recognition for Nakahira. His first solo show, Degree Zero—Yokohama, was held in 2003 in Yokohama, where the artist lived at the time. He continued making similar but slightly different photographs near his home—often returning to the same objects or places again and again, in an anti-“Botanical Dictionary” manner—until 2011, when his health began to fail. In his final works he focused on the unique qualities of each of his subjects, rejecting generalizations and classifications and acknowledging a photograph’s radical ability only to point to the world.

— Masashi Kohara

Translated from the Japanese by Jens Bartel

-

Lieko Shiga

1980, Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture

The camera has been compared to many things—a weapon, a tool, and a witness, among them—but Lieko Shiga (b. 1980) likens it to a portal. Though her practice is firmly rooted in location-specific fieldwork and the human experience, she uses the camera to reimagine the world around her as a phantasmagoria, transporting viewers to a fiercely foreign realm through elaborate staging and lighting, the active participation of her subjects, and a liberal use of colored filters rather than digital manipulation. “I have been described as an alien,” she has remarked proudly, attempting to explain her singular artistic vision.[1]

Growing up in a suburb of Okazaki, where much of the labor force is employed by Toyota and other manufacturing companies, Shiga believed “everything I [saw was] just an illusion . . . nothing in my environment was real.”[2] Her idea that the motions of daily life constituted a magic act—with someone at work behind the curtain, pulling the strings—informed her desire to participate in life, rather than merely observe it. For years she studied classical ballet until, as a teenager, her physical development prevented her from advancing. Around the same time she began experimenting with her parents’ point-and-shoot camera. Photography immediately registered as a tactile experience and soon displaced dance as her preferred form of self-expression. She has recalled, “Having the image I envisaged reproduced on the physical material of photographic paper, and being able to hold it in my hand, was both shocking and pleasurable. I felt an immense separation between the image in my hand and my own body, and I found that separation extremely sensual. I think that at that moment I discovered my existence through the device of the camera.”[3]

In 1999 Shiga left Japan to study fine art at Chelsea College of Arts in London, where she lived for about seven years. As a student she photographed people in her immediate sphere—friends, her roommate, neighbors—in haunting scenes that make reference to nineteenth-century spirit photography. Her first pictures from that period appear in the book Lilly (2007), which Shiga considers an attempt to re-create the “atmosphere of her adolescence,” something akin to “child’s play, but the dark side of it.”[4] That year she also released Canary, a compilation of photographs made between 2006 and 2007. If Lilly visualizes her internal angst, Canary represents her complicated engagement with society and the external world. Shiga received the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award for the two publications.

At the end of 2008, following a 2006 residency in Miyagi Prefecture that introduced her to the insular region of Tohoku, Shiga moved to Miyagi permanently. She set up a studio in coastal Kitakama and established herself as the town photographer, documenting residents and local activities from baseball games to town hall meetings. Over time she built an unofficial archive of the village through photographs and oral histories, which she envisioned combining in a massive project about the community and its past. But on March 11, 2011, the Tohoku earthquake triggered a tsunami that devastated Kitakama and shifted the course of her endeavor. Shiga survived, but both her home and her studio, along with the work and possessions stored there, were swept away. Over the next two years she resided in temporary shelters and occupied her time with projects such as cleaning and digitizing anonymous photographs found among the debris. In 2013 she exhibited and published Rasen Kaigan (Spiral Shore), featuring images of Kitakama and its residents after the tsunami as well as photographs that predated the event, which had been safely stored in Tokyo. While the project can be read as “an elegy to a community that has been dislocated,” Shiga is reluctant to let the work be defined by the disaster.[5] Deeply personal and collaborative, it allowed Shiga to realize that “for about a decade following my encounter with photography, I took photographs with the feeling that I was somehow exerting control over the world within me.”[6]

Shiga continues to live and work in the countryside in Miyagi Prefecture, making photographs that examine the local environment, often in relation to broader sociopolitical issues, philosophies, and human concerns. Her recent project Human Spring (2019) considers how the landscape of Miyagi represents both the evolution of Japanese society during the Heisei era (1989–2019) and the cycle of life and death.

— Amanda Maddox

Notes

Lieko Shiga, conversation with the author, March 5, 2019.

Shiga, conversation with the author, December 4, 2018.

Lieko Shiga, adapted from Rasen Kaigan: Notebook (Tokyo: AKAAKA Art Publishing, 2012). Translated by Jeffrey Hunter.

Shiga, conversation with the author, May 11, 2019.

Anne Nishimura Morse and Anne E. Havinga, “Reflections in the Wake of 3/11,” in In the Wake: Japanese Photographers Respond to 3/11 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2015), 152.

Shiga, adapted from Rasen Kaigan: Notebook. Translated by Jeffrey Hunter.

-

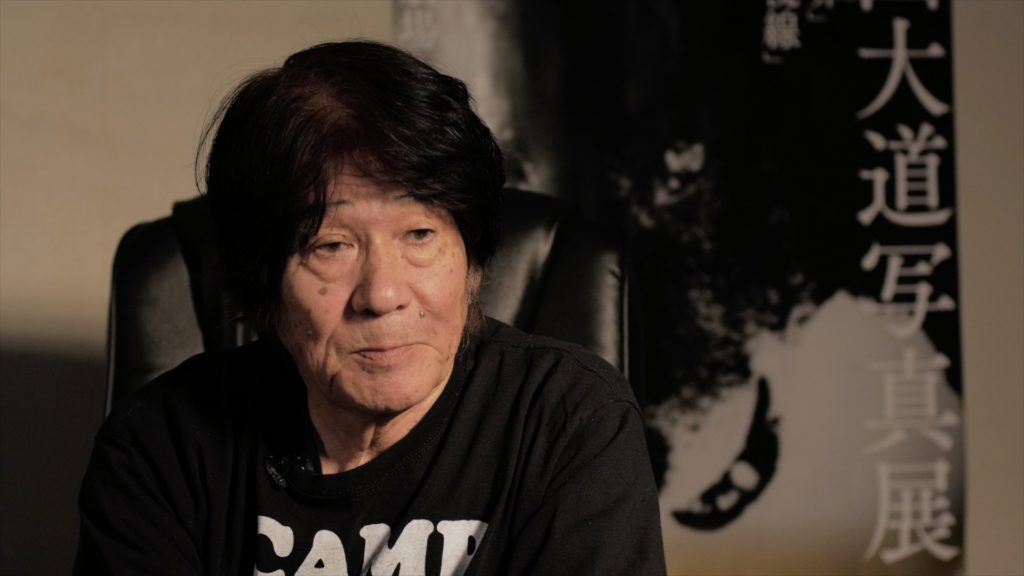

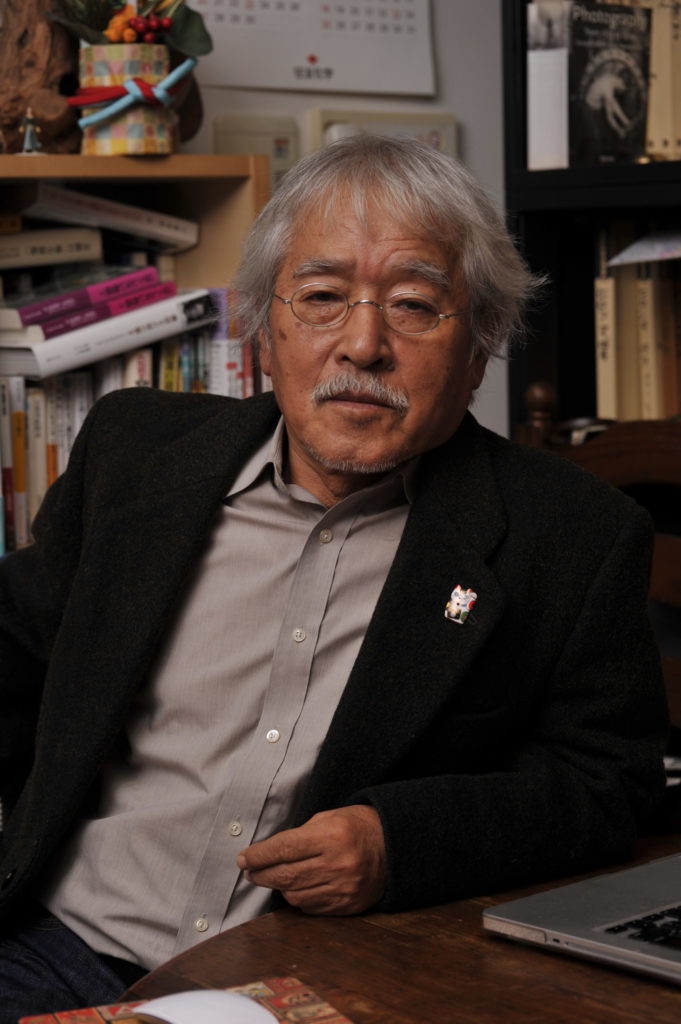

Shomei Tomatsu

1930, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture

2012, Naha, Okinawa Prefecture

Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012) created pictures that balance perilously between despair and admiration, anger and delight, articulating the essential conflicts he found in his country after World War II. Sharp and elegant, they are not so much descriptions as they are records of fleeting, unremarkable moments. The first photographer to explore the experience of postwar Japan and its ambiguous relationship to the United States, Tomatsu would portray this subject more thoroughly and intensely than any other photographer. Only toward the end of his life was the issue of the Americanization of his country somewhat lessened in his work.

Born in Nagoya, Tomatsu was fifteen years old when the war ended. “To have experienced only suffering, that is the characteristic of the children who knew the war,” he said.[1] He found his way to photography with the help of a sympathetic teacher and the modestly scaled, beautifully printed photography books for the general reader produced by the publisher Iwanami Shoten, for whom he would work briefly, from 1954 to 1956. Photography suited Tomatsu because he could work on his own, and most of his projects were self-assigned. His earliest subjects constituted an inquiry into the way his country was changing in the postwar years. He later recalled: “After the defeat, darkness and light became clearly visible and values shifted 180 degrees. . . . My most impressionable years were spent during those times, and that intense experience became a filter through which I’ve seen things ever since.”[2] Tomatsu’s first series, Disabled Veterans, Nagoya (1952) and Pottery Town, Seto, Aichi (1954), record poverty after the war and the persistence of a prewar artisan culture. Later, in Home, Amakusa, Kumamoto (1959), he acknowledged the beauty and richness of traditional Japan but also the unsustainability of the kind of life led in rural communities.

Quite early in his career Tomatsu discovered that his work, while depicting specific subjects, could resonate metaphorically as well. Defending his work against the criticism that he made a “photography of impressions” rather than truthful reports, he stated that he “did not remember ever discarding factual fidelity” but that “to avoid the sclerosis of photography, it was important to cast out the evil spirit of ‘reportage.’”[3] Thus a picture of the mud-spattered legs of a worker seen from behind, shovel in hand, shows an honest understanding of the conditions facing the country, especially for its rural inhabitants in the 1950s and 1960s, but Tomatsu's photographs also speak to Japan’s renewal, its essential fecundity. In making pictures that were engaged in his country’s issues without being journalistic, Tomatsu was fortunate to have support from magazines directed at amateurs, including Camera Mainichi, the principal publisher of important new photography in Japan, under the direction of editor Shoji Yamagishi.

By 1959 Tomatsu had established a pattern of finding subjects and returning to them later, or finding subjects in the present that were about the past. Chief among them was the condition of postwar Japan and the persistence of its past in the modern state, as in the Memory of War, Toyokawa, Aichi series (1959). “It was from the ruins of war that Japan was reborn, Phoenix-like,” he stated. “It was only from here that it could make a fresh start.”[4] His series Floods and the Japanese (1959), prompted by the destruction of his childhood home, represents both the devastation and the regenerative potential of flooding. Also in 1959, he began to document American military bases around Tokyo in the series Chewing Gum and Chocolate. This subject was especially resonant at that time, when the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty was being renegotiated amid intense domestic opposition.[5] Of all his subjects, it would be the one he persisted in most forcefully and inventively. The country’s active growth during this period is equally important to understanding the arc of Tomatsu’s career. As acknowledgment of this resurgence, Japan hosted the Olympic Games in 1964 and 1972 and the World Exposition in 1970, events that Tomatsu referenced in his work.

In addition to his own practice as a photographer, Tomatsu actively promoted photography in Japan. In 1959 he joined Ikko Narahara, Kikuji Kawada, Eikoh Hosoe, Akira Sato, and Akira Tanno to form the influential agency VIVO, modeled generally on the photographers’ cooperative Magnum, established twelve years earlier in Paris. Although VIVO disbanded after two years, it embodied the creative energy of the best postwar photography. In 1968, assisted by Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki (who would later found the journal Provoke), Tomatsu organized the groundbreaking exhibition A Century of Photography: A Historical Exhibition of Photographic Expression by the Japanese (also known as A Century of Japanese Photography). The first historical presentation of photography in Japan, surveying the period 1840 to 1945, it was shown through the Japan Photographers’ Association at the Seibu department store in northern Tokyo, for many years an important venue for contemporary art. Tomatsu was the central figure in New Japanese Photography, organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1974; the exhibition traveled to SFMOMA the following year. This was the first recognition by an important museum outside Japan that significant work was being created by Japanese photographers.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s Tomatsu bore witness to the vibrant youth culture of Tokyo, mainly in evidence in Shinjuku, as well as the student protests there, seen especially in the Protest, Tokyo series (1969). Tomatsu traveled to Nagasaki for the first time in 1960 to photograph the victims of the 1945 atomic bombing. These pictures would be published, along with Ken Domon’s photographs of the hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bombings) in Hiroshima, the following year as Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961, issued only in Russian and English. Tomatsu also photographed objects that showed the effects of the nuclear bombing: a stopped wristwatch, a commonplace bottle distorted by the intense heat, and details from the city’s cracked and ruined ancient Catholic cathedral. He would return to Nagasaki periodically over the years and later lived there. In 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War, he began to examine the special history of Okinawa, still heavily occupied by American forces as the principal military staging site in Japan for the conflict in Vietnam. His first trip there took place under the auspices of Asahi Camera, which published the resulting series; his book Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa was published by Shaken later that year. The renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in 1970 focused Tomatsu’s attention, and that of many younger Japanese people, on the danger posed to the country by U.S. nuclear weaponry, even as social liberalization and exuberant economic resurgence were partly attributable to the American postwar presence. He returned to Okinawa twice in 1971, and again in 1972 to witness the return of the islands to Japanese control.

With the publication of The Pencil of the Sun in 1975, Tomatsu turned his attention from the American forces in Okinawa to the island’s ancient culture, finding a pre-Japanese culture still very much in evidence there. In his later work the American presence gradually became less of a focus. In the series Plastics (1988–89), he documented debris he found cast up on the shores of Chiba, where he then lived. After moving to Nagasaki in 1999, he photographed schoolchildren on the city’s streets and the aging hibakusha Senji Yamaguchi, whom he had photographed previously, in 1962—now no longer a victim but, seen from behind, an older man enjoying a boat ride. Tomatsu spent the last two years of his life in Okinawa.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

Shomei Tomatsu, “The Original Scene,” in Traces: Fifty Years of Tomatsu’s Works (Tokyo: Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1999), 183. In Japan his generation was called the “Heretical Generation,” he writes: “It was a label that was affixed to the children who had experienced the war on both sides, regardless of whether they were on the winning or losing side.” As such, the term was used to refer to the American Beat generation and the French New Wave as well. Ibid., 183.

Shomei Tomatsu, Chewing Gum and Chocolate: Shomei Tomatsu, ed. Leo Rubinfien and John Junkerman (New York: Aperture, 2014), 19.

Shomei Tomatsu quoted in Nakahara Atsuyuki, “Tomatsu Shomei—Fifty Years of Innovation,” in Traces, 191.

Shomei Tomatsu quoted in Traces, 184.

Its passage was forced through in 1960, to the dismay of much of the population.

-

Hiromi Tsuchida

1939, Minamiechizen, Fukui Prefecture

The opening sequence of Zokushin: Gods of the Earth (1976), a photobook by Hiromi Tsuchida (b. 1939), shows a group of people picnicking in the woods above a rice paddy. As the already drunken farmers grow progressively more intoxicated, they roll around on the ground, joke with one another, and gesture at the photographer. The pictures are black and white, and in this sense, they belong to an established tradition of documentary photography in Japan. However, the playful streak that runs not just through this series, but through Tsuchida’s entire career, sets his work apart from that of his predecessors.

After working as a commercial photographer, from 1964 through 1966 Tsuchida studied at the Tokyo College of Photography in Hiyoshi, Yokohama, where he learned a conceptual approach to the medium from the noted critic Koen Shigemori. Zokushin was his first major series, published across several issues of the magazine Camera Mainichi before the pictures were collected in a book. The project was the result of his travels through Japan in the early to mid-1970s, as he sought out ways of life not yet homogenized by the capital flowing from urban centers. While some of the photographs were taken in Tokyo’s Asakusa district—“pleasure quarters” in days gone by—the bulk of them were made in more remote areas. Several pictures show the encroachment of the tourism industry, one of various factors that would eventually flatten the distinction between “urban” and “rural.” The object of Tsuchida’s attention, however, was not so much the scenery as it was the local cultures and people. Two of his photographs in Aomori Prefecture, for example, show a group of women in traditional dress and a singer in the midst of a performance. The images focus on the figures’ clothing and expressions; the singer’s face, in particular, projects controlled yet intense emotion.

Whereas in Zokushin Tsuchida dealt with people in rural areas soon to be swallowed up by urban ways of life, in his next major series, Counting Grains of Sand (1990), he trained his gaze firmly on the inhabitants of major cities. The book starts with snapshots of a few scattered individuals, but eventually more and more figures fill the frame, culminating in images of the crowd that gathered in front of the Imperial Palace after the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989. Thousands of men and women are packed into each of the final photographs, revealing the wry meaning of the title: people are no more than grains of sand, infinitesimal parts of a vast collective. Tsuchida has also depicted cities with a view to history—he has made photographs in Hiroshima and Berlin since 1973 and 1983, respectively, often returning to the exact same spots to make new exposures years later.

Tsuchida extended Counting Grains of Sand in color in the 1990s and beyond, capturing crowds at popular tourist destinations throughout Japan. In these later works he used new technology in a somewhat cheeky way, inserting himself digitally into all of the pictures. This gives them an almost zany, Where’s Waldo? quality, and it seems to show that Tsuchida considers himself no better than, or different from, those he records on film. He has also experimented with digital techniques in other bodies of work—in 1988 he started photographing himself nearly every day, long before such projects became viral sensations, and in 2008 he made a time-lapse video from the images. In these ways Tsuchida continues to bring a sense of humor and playfulness to his examination of social phenomena.

— Daniel Abbe