“The show is its process. The artworks are merely archaeological remnants.”

—Tim Drescher, Progress in Process

In the spring of 1982, Galería de la Raza/Studio 24 in San Francisco’s Mission District exhibited a mural titled In Progress that, now, only exists online and on paper. Students, researchers, and other interested audiences may discover it through 35mm slides that were digitized and made available online.[1] There is also a printed exhibition catalogue that offers an interpretive and visual record of the mural’s creation and the artists who made it.[2] Conceived by Galería de la Raza director René Yañez, In Progress was a multi-panel mural that he created with nineteen other artists, all of whom are major contributors to the region’s political, cultural, and art histories. Focused on process over product (or the finished artwork), the artists created sixteen mural panels that addressed the syncretic origins of Latinx peoples of the Americas. From the history of Latinx representation in U.S. mainstream culture to critiques of the colonial turned national forces of power that historically shaped and continue to undermine Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, the artists created political commentaries and visual narratives of the Central American solidarity movement in San Francisco during the 1970s and 1980s.[3] Although In Progress no longer exists in a physical or complete form, its significance lingers in its archival traces;[4] the existing records (both print and digital) are primary sources of art history for the Mission District. Together, these sources reveal layers of artistic influence and innovation for murals of the San Francisco Bay Area.

On exhibition from May 4 to June 12, 1982, In Progress was never intended to be a permanent mural; rather, its purpose or artistic intention was the realization of its idea. Put another way, In Progress focused on the art of building relationships by bringing different people together to create art that exists only in the shared steps of its making. The relational concept inherent to the In Progress mural resonates in the sociopolitical philosophies of the 1960s and 1970s antiwar, student, and civil rights movements in the Bay Area. This era gave rise to the community mural movement in the United States and continued an international trajectory of populist art across the Americas. Yañez’s idea for the mural was also influenced by modern art events of the early twentieth century, particularly Diego Rivera’s creation of the portable fresco in 1931 and José Clemente Orozco’s experimentation with the form in 1940.

As a concept for mural making, In Progress connects both art historical eras to the socially engaged art of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. From materials choices to advancements in accessibility through digital media, In Progress encompasses a conceptual art history that spans modern and postmodern timelines. Today, its community-building praxis resonates in the relocation of Rivera’s 1940 mural Pan American Unity from its longtime home at City College of San Francisco to the street-accessible Roberts Family Gallery at SFMOMA in 2021. Created as a portable fresco, Rivera’s mural produced a local and transnational dialogue that resounds in the collaborative choices made, on a smaller scale, in the creation and exhibition of In Progress.

Retracing Shared Steps: An Exhibition Catalogue as Historical Artifact

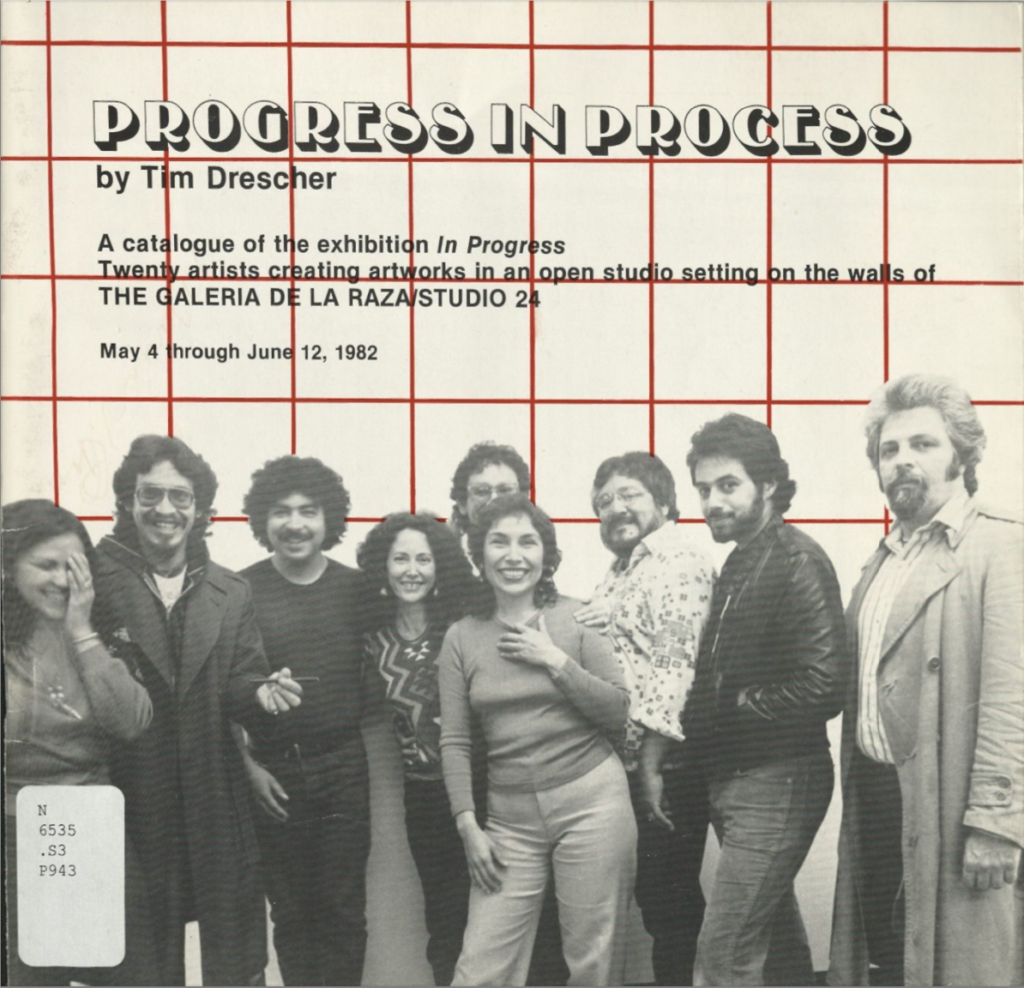

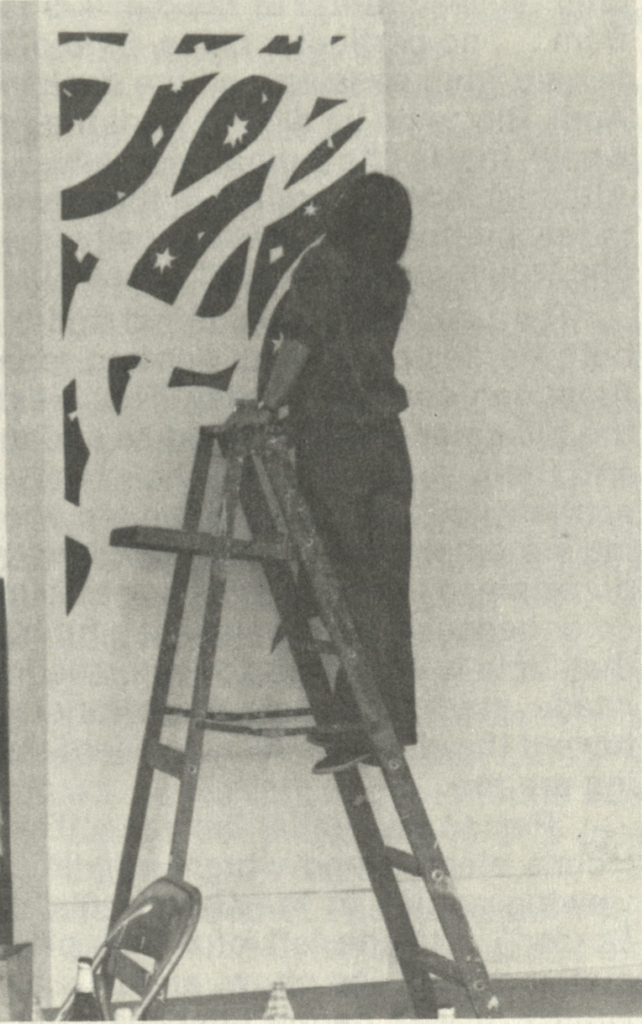

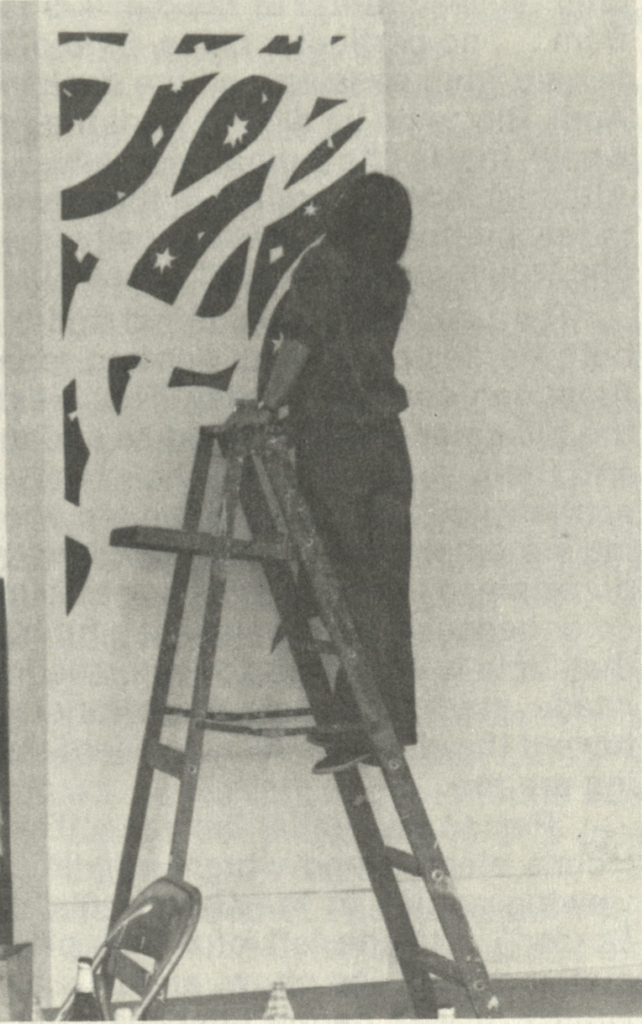

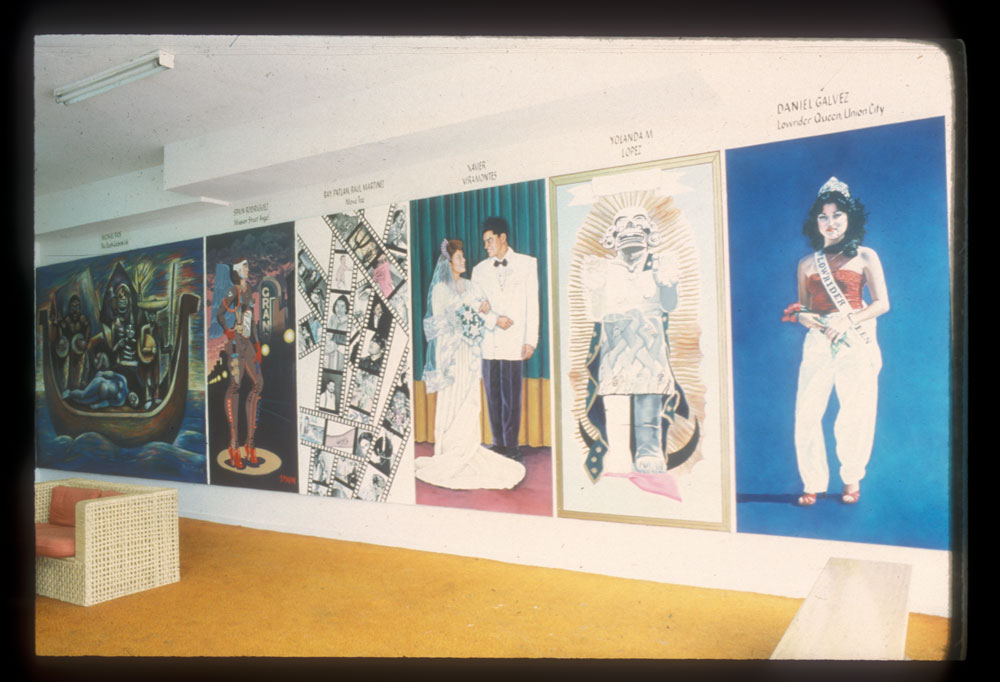

While In Progress was a temporary mural, its development and display were witnessed, recorded, and preserved by public art historian Tim Drescher in the mural’s exhibition catalogue Progress in Process. The catalogue’s cover focuses on the collective spirit of the mural because it does not depict the actual artwork but, instead, features a photograph of nine of the artists who made it. A subtitle placed directly above their portrait announces, “Twenty artists creating artworks in an open studio setting on the walls of the Galería.”[5] Along with René Yañez, the In Progress artists included Miranda Bergman, Tony Chavez, Juan Fuentes, Daniel Galvez, Rayvan Gonzalez, Nancy Hom, K.O., Lisa Kokin, Yolanda López, Raúl Martínez, Regina Mouton, Emmanuel Montoya, Jane Norling, Ray Patlán, Michael Ríos, Patricia Rodriguez, Spain Rodriguez, Herbert Sigüenza, and Xavier Viramontes. While seven of the artists collaborated on three panels for the mural, the rest of the group created individual sections; each artist engaged in public discussions with one another, patrons, and pedestrians as the Galería’s “doors were open from noon until six o’clock or later everyday [and] everyone was free to come in and look and talk with the artists as they worked.”[6] Repurposing the gallery as an open studio, the artists challenged social expectations for gallery visitors who look quietly at finished artwork, read wall labels, listen to guides, and rarely speak above a whisper to anyone about their impressions of the art.

The In Progress artists also used the gallery space to perform art criticism, a formal and, typically, verbal method of teaching and learning about one’s artwork that derives from institutional training. Most of the artists had studied Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, and street art, as well as the rise of New Genres at various arts colleges and universities. Drescher cites a planning meeting for the mural on April 21, 1982, that transformed into an artists’ critique in which the group had “a chance to discuss proposed sketches, to criticize and be criticized among peers. These artists, all professionals, had not had such an opportunity since art school.”[7] Connecting the community-centered component of the mural with the academic discourse in which the artists were educated, Drescher’s use of terms like “open studio” and “artists’ critique” is intentional because, despite their institutional knowledge and training, these artists, among other BIPOC artists, were historically excluded from contemporary and modern art museums; they were also largely absent from art exhibitions, catalogues, and scholarly analyses of aesthetic innovation, trends, and techniques.

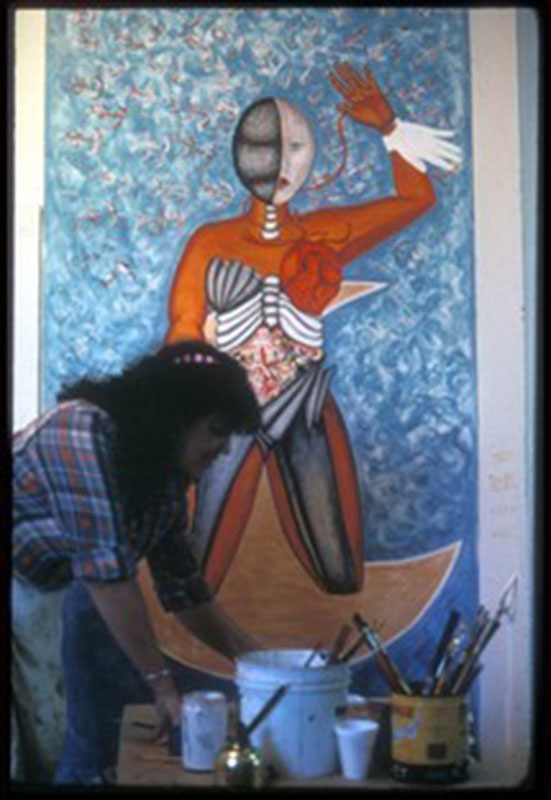

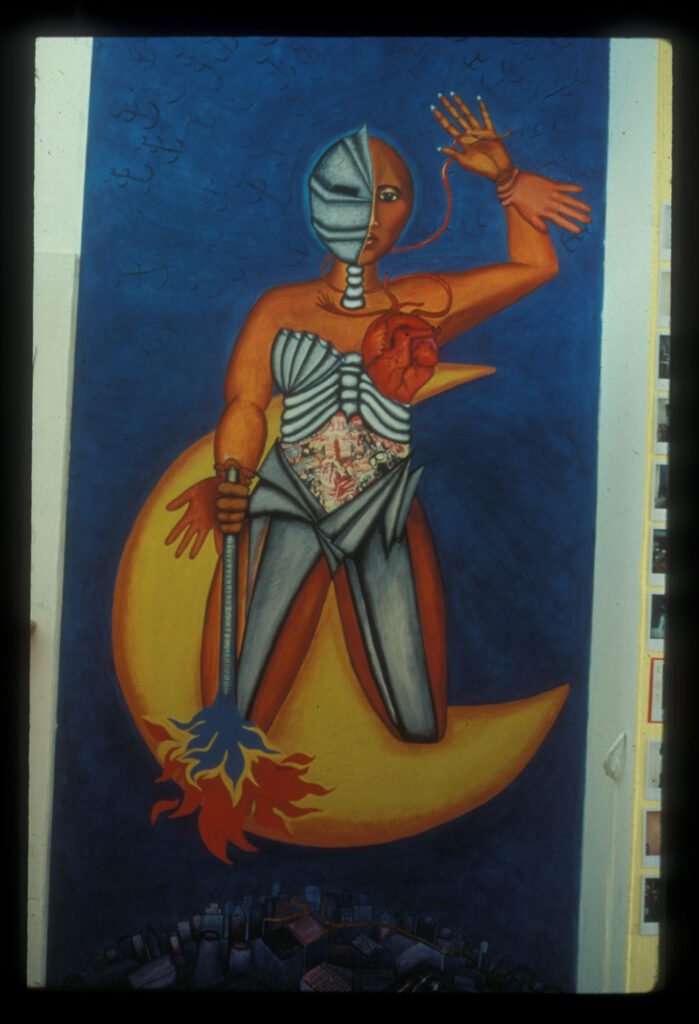

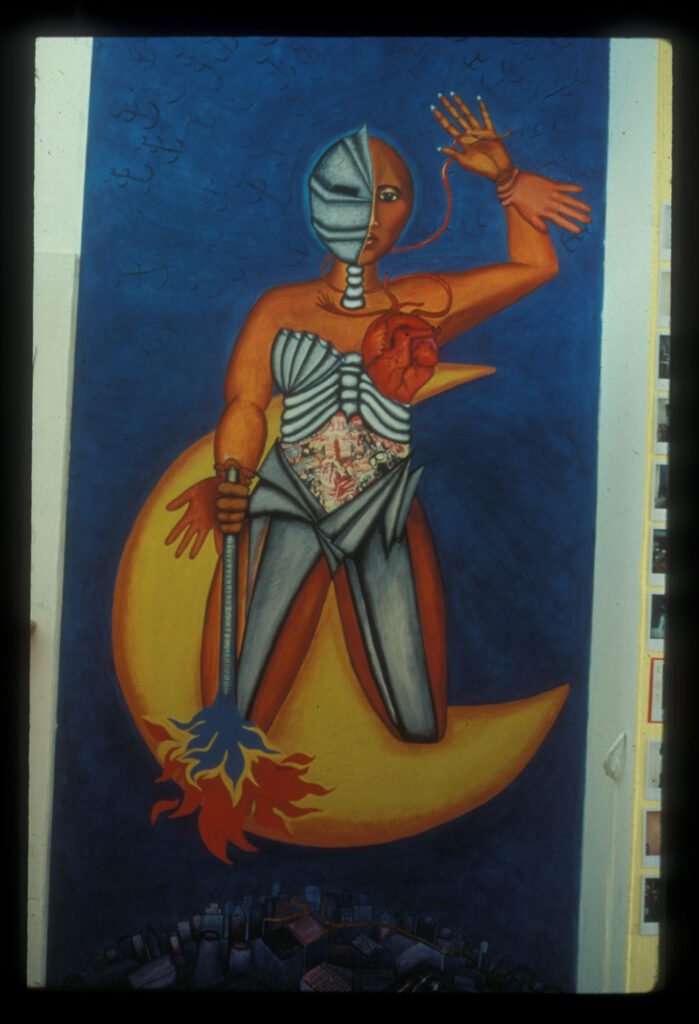

In Progress artist Patricia Rodriguez completed her bachelor of fine arts in 1972 at the San Francisco Art Institute and her MFA at CSU Sacramento in 1975.[8] A painter and mixed-media artist, Rodriguez cofounded Mujeres Muralistas, a women’s art collective that created several of San Francisco’s vanguard Latinx murals including Latino America (1974). For the In Progress mural, Rodriguez merged her knowledge of Surrealism with political events and crimes against humanity happening in El Salvador in a painting of pre-Columbian deity Tlazoltéotl; her fusion of different cultural knowledges formed a powerful commentary on the sins of modern wars and their resonance in the colonial conquest of Indigenous peoples of the Americas.[9]

Yolanda López also created a panel that explored cultural fusions of religious beliefs and spirituality in the postconquest (now contemporary) Americas. Completing her associate arts degree in 1964 from the College of Marin, López spent several years studying at San Francisco State University (1966–69). She finished her bachelor of arts in painting and drawing at CSU San Diego in 1975 and earned her MFA in 1978 at UC San Diego.[10] During this time, López created canonical images of Chicana/o and Latinx art histories via the newspaper Basta Ya!.[11] She also served as an advisor for a mural created by Chicana adolescents in the late seventies at San Diego’s Chicano Park.[12] López’s visual contribution to In Progress was part of her iconic Guadalupe series (1981–88) in which she framed the pre-Columbian goddess Coatlicue with the iconic rays that surround la Virgen de Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico. Not without controversy, the merging of Indigenous and Catholic imagery in López’s mural panel (and series) was a powerful intervention on Chicana/o culture as she visually communicated the persistence of Indigenous worldviews in the matrilineal ancestries of colonized peoples.[13]

Graduating from the Pratt Institute in 1971, Nancy Hom cofounded the Asian American Media Collective in New York City before moving to San Francisco in 1974, where she worked at and later served as director of the Kearny Street Workshop, “the oldest surviving multidisciplinary Asian American community arts organization in the United States.”[14] Hom’s mural panel “Celebration of the Spirit” presented a vibrant image of a Black woman dancing during the Mission District’s Carnaval festival. Hom was intentional in her focus on joyful acts of resistance by people of color “celebrating themselves” in their neighborhoods and communities.[15] Now in its fourth decade, Carnaval San Francisco honors the Latin American, Caribbean, and African diasporic communities that shaped the syncretic culture of the Mission District. Along with several colleagues collaborating on the In Progress mural, Hom represents a generation of Bay Area artists in the late twentieth century who built multiracial and interethnic networks of community support and mutual aid through artistic production as a lived commitment to social justice.[16]

A Mixed Blessing: Sociopolitical Exclusion & Aesthetic Innovation

On the heels of the sixties and seventies civil rights movement in the United States, multiculturalism emerged as an educational initiative within institutions of higher education, libraries, and museums, shifting official perspectives and curatorial choices by the eighties. BIPOC artists, as well as women and queer artists, began to be exhibited and collected. The multicultural turn in modern art museums and commercial galleries was a “mixed blessing” for many of these artists; while it offered more funding and exposure, it also changed their audiences, challenging their relationships to the communities from which they came and the political principles they espoused.[17] The In Progress mural was a direct response to the assimilation and commodification of people of color, women, and queer artists into institutional collections and shows. By creating the mural with each other and a diverse audience, the artists recentered the concept of unity over sameness, grounding the mural in the coalitional politics that many of them had developed as an artistic process long before multiculturalism.[18]

Their intervention on an exhibition space also anticipated the trend of public art actions and community events held inside museums and galleries and deemed relational aesthetics in the early twenty-first century.[19] Assembling people as a community inside of Galería de la Raza, Yañez and his colleagues transformed the making of a mural into a public commons, where artists, residents, pedestrians, and patrons discussed the artwork on equal(izing) ground: “When visitors talked,” Drescher writes, “the artists listened, especially those who had experiences painting community murals (ten of the twenty artists).”[20] This was familiar arts praxis for half of the In Progress artists because they were used to being hailed by people on public streets as they created murals on tenement walls, restaurant facades, and garage doors lining the Mission’s alleyways. The community mural movement often involved building consensus among residents, small business owners, and artists, as well as coauthorship and anonymity via the act of writing names of student groups or artist collectives on murals instead of their individual names.[21] Taking their experiences of impromptu public dialogues inside the gallery and creating collective ownership or investment in the artistic creation, the In Progress artists produced a space of inclusion as opposed to transaction.

In tandem with their knowledge of creating community murals, several of the In Progress artists were also skilled printmakers and well-versed in operating graphic arts workshops for political art production. Growing up during the U.S. civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, many of the artists participated in the Third World Liberation Front strikes at San Francisco State University and University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley), in 1968 and 1969, respectively. Collective action for educational change, calls to end the Vietnam War, and raising awareness about local issues impacting BIPOC communities necessitated visual tools of communication. From screen-printing posters and designing graphics for underground newspapers to holding community meetings and student gatherings, these artists founded and/or directed “workshop” spaces in the Mission District.

Like his colleagues Hom and López, Juan Fuentes worked at and later directed Mission Gráfica, founded in 1977 and housed within the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts (MCCLA). After volunteering his art skills at El Tecolote, the historical Mission community newspaper, Fuentes worked for the silkscreen center La Raza Graphics. Having studied at San Francisco State University during the Third World Liberation Front student strikes, Fuentes, among his colleagues, was deeply aware of the graphic arts of the Mexican Student Movement (MSM) through the circulation of alternative press publications.[22] His artistic choices reflected New Left principles, which emphasized coalitional politics for BIPOC communities across the Americas.[23]

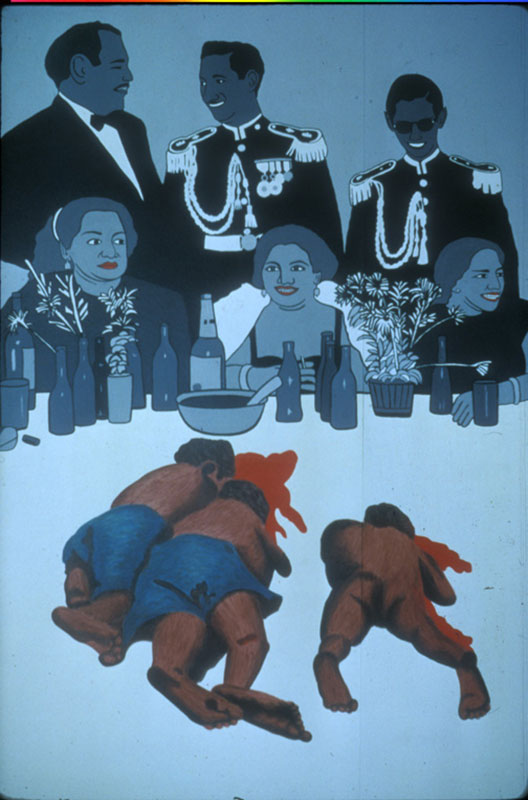

The panel that Fuentes created for the In Progress mural exemplifies his political solidarity with Third World Liberation movements because he collaborated with Regina Mouton—a woman of color and Bay Area artist, activist, and educator—on a dinner scene of military officials and their spouses. Titled “The Last Supper” to connote the Christian allegory of the final meal before the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, the panel featured three lifeless bodies of children in the foreground. Their brown bodies are framed by distinct outlines of red paint, which signify blood and contrast with the white banquet tablecloth. The military elite sit before the children, smiling and imbibing. By utilizing color blocking, an early twentieth-century painting technique that was reinvigorated by Abstract Expressionist and Pop artists in the mid- to late twentieth century, Fuentes and Mouton visually communicated the sacrifice of innocent life amid the Central American civil wars that advanced the economic agendas of powerful nations.

Murals on the Move: Inventing the Portable Mural

The visual language that Fuentes, Mouton, and their colleagues created for In Progress built upon art historical trends and techniques of modern art. The muralists also engaged sixties and seventies iconography to express shared struggles and histories of resistance for BIPOC communities across the Americas. But the idea of creating accessible art—or art that would reach people beyond the walls of museums and galleries—was part of an ongoing, transnational trajectory of artistic production. From the populist images of Mexico’s El Taller de Gráfica Popular to the monumental murals of the Mexican artists of the early twentieth century, Fuentes, among his colleagues, had been discussing concepts of revolutionary art for decades, especially with René Yañez.

Yañez’s preference for creative dialogues as a process of art making is situated between the Happenings of the 1950s, which emerged out of Dadaism and Surrealism, and the political rise of student activism amid the Cold War turned proxy wars of the late twentieth century. A founding member of the vanguard Chicano art collective the Mexican American Liberation Art Front (MALA-F), Yañez participated in salon-style gatherings of Chicana/o artists, students, and emerging academics long before the In Progress mural. These gatherings included students and faculty of the burgeoning Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley and the Ethnic Studies College at San Francisco State University.[24] In 1968, the MALA-F’s name echoed the larger political moment, but the MALA-F artists also took direct inspiration from los tres grandes or “the three great” Mexican muralists of the early twentieth century: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

A statement published by MALA-F artists in the community newspaper La Bronce in 1969 illuminates their connection to the revolutionary art of the modern Mexican artists who understood “the importance of the pueblo to the revolucion [and] rebelled against the conventional European influenced arts. . . . They encouraged and practiced the idea that art was meant for the pueblo not for a ‘cultured few.’ . . . The Revolucion is now 1968 and we are still struggling.”[25] Connecting with Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros outside institutional narratives and official art histories, the MALA-F artists engaged their political values idealistically, adopting and adapting the liberating force of making art for people, if not addressing the more complicated realities of Pan-Americanism and the agendas of state-sponsored murals in Mexico and their powerful patrons in the United States.[26]

One of the ways that Yañez integrated the “pueblo” or populist principles of art making into the design of In Progress was the concept of a moveable mural made in front of an audience. The idea originated in Rivera’s creation of a portable fresco to meet his institutional sponsors’ goals of “offering New York’s museum-going public a glimpse” of Mexican mural making.[27] Rivera created eight portable fresco panels specifically for a retrospective exhibition of his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1931.[28] Prior to the show’s opening in December of that year, Rivera completed three murals in the Bay Area, including Making a Fresco, the Building of a City (1931) in the San Francisco Art Institute’s student gallery.[29] In 1940, Rivera would complete his ten-panel fresco, The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, known as Pan American Unity, for the Golden Gate International Exposition on San Francisco’s Treasure Island. It was the largest portable fresco created by Rivera and his last made in the United States.

Moved out of storage in 1960, Pan American Unity was installed in 1961 in a theater lobby at City College of San Francisco, renamed the Diego Rivera Theater in 1993.[30] Rivera’s local murals were certainly well known to Yañez, as well as members of MALA-F and the In Progress artists. But the idea of a portable mural—as a mode of disseminating “people’s histories” to audiences beyond those at the modern art museum—was an emergent concept for muralism, and one that continued to evolve in the content and form of In Progress.

Latin American art historian Anna Indych-López writes that portable murals “are not conceived within a specific architectural setting. Instead, these are large-scale panels constructed with a latticework substrate covered by concrete and several coats of plaster, held together by a heavy steel frame.”[31] Subsequently, in their very form or material construction, the portable mural, (and in this case, the portable fresco), “break with the traditional (academic) concept of the mural as a form of wall decoration and necessarily reject the Mexican elaboration of the mural as a form of social expression dependent on government buildings for mass public communication.”[32] Prior to the In Progress mural in 1982, the community mural movement had already broken architectural traditions for murals in the United States by taking up space on walls without sanction. From the Wall of Respect (1967) in Chicago, in which artists of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) painted Black heroes and icons on an abandoned building and in direct engagement with residents, to performance murals by the Chicana/o art collective Asco in the early seventies, the Mission District’s murals also narrativized an entire neighborhood with painted histories of BIPOC diasporas that formed dynamic communities in San Francisco. Soon, institutional and government funding followed and supported community mural projects, and the Mission District maintains this mode of visual communication today.[33]

As Rivera’s innovation of the portable fresco spread, his contemporary José Clemente Orozco “manipulated the medium in order to demonstrate the technique of fresco and, ostensibly, the iconography of public mural painting in Mexico.”[34] Both Rivera and Orozco had “‘performed’ the fresco technique for the public,” with Rivera painting panels in front of MoMA patrons during his retrospective, and Orozco doing so for MoMA’s exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art in 1940.[35] But for Orozco’s portable mural Dive Bomber and Tank (1940), which encompasses six panels that “used the modernist idiom of abstraction” to create powerful political art, he also “proposed displaying the mural in six distinct arrangements, many of them more abstract than the ‘standard presentation’” and some that did not include all six panels.[36] Likening a painting to a poem that is “made of relationships between words, sounds or ideas,” Orozco’s statement on his mural in the Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art intersected modernist ideas of linguistic interplay, from repetition to multilingual alliteration, in the poetry of the early to mid-twentieth century.[37] His arrangements of the mural panels also anticipated another conceptual element of In Progress regarding the actual movement, perhaps, migration cycle of this late twentieth-century mural.

Beyond the Wall: Materials Choices & Digital Futures

Rarely do we imagine murals moving from their locations or having the ability to travel beyond their walls. But murals can be both mobile and mobilized by an idea through the processes used in their making as well as in the documentation of their creation. With increasing access to digital media for preserving and archiving historical records like printed catalogues, photographs, and works on paper, murals can be seen long after they cease to exist in their initial forms or locations.[38] Because of electronic imaging technology like the portable document format (PDF), several audiences have access to the In Progress exhibition catalogue, allowing them to track the steps of its creation. An even wider audience may glimpse the In Progress mural through the 35mm slides that were digitized and shared online by UC Santa Barbara’s California Ethnic and Multicultural Archive (CEMA).

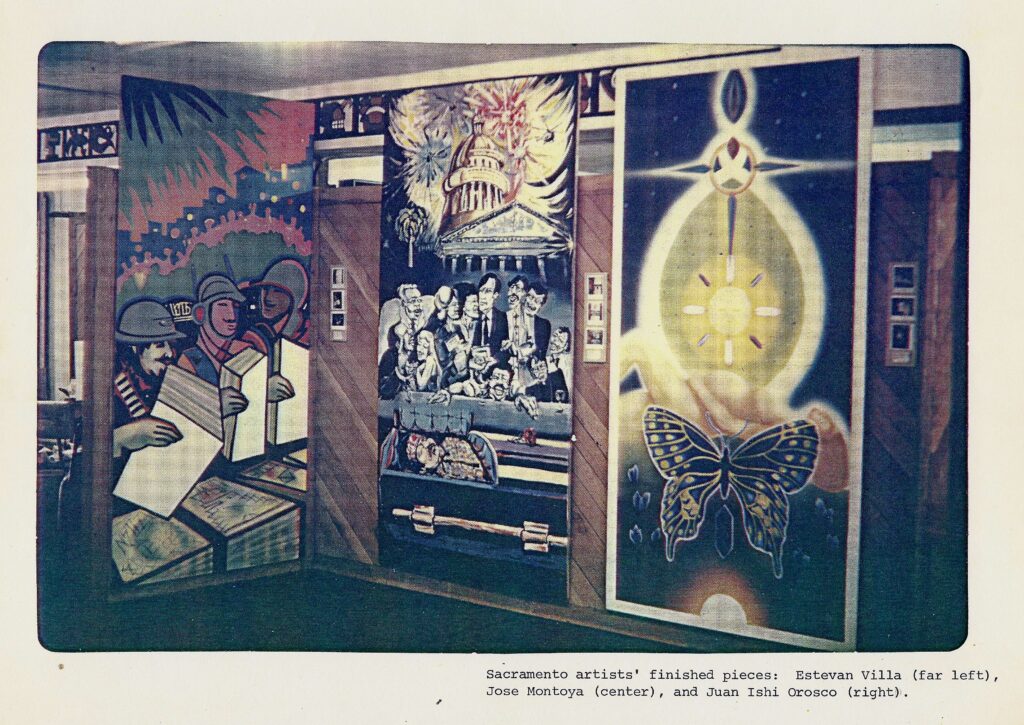

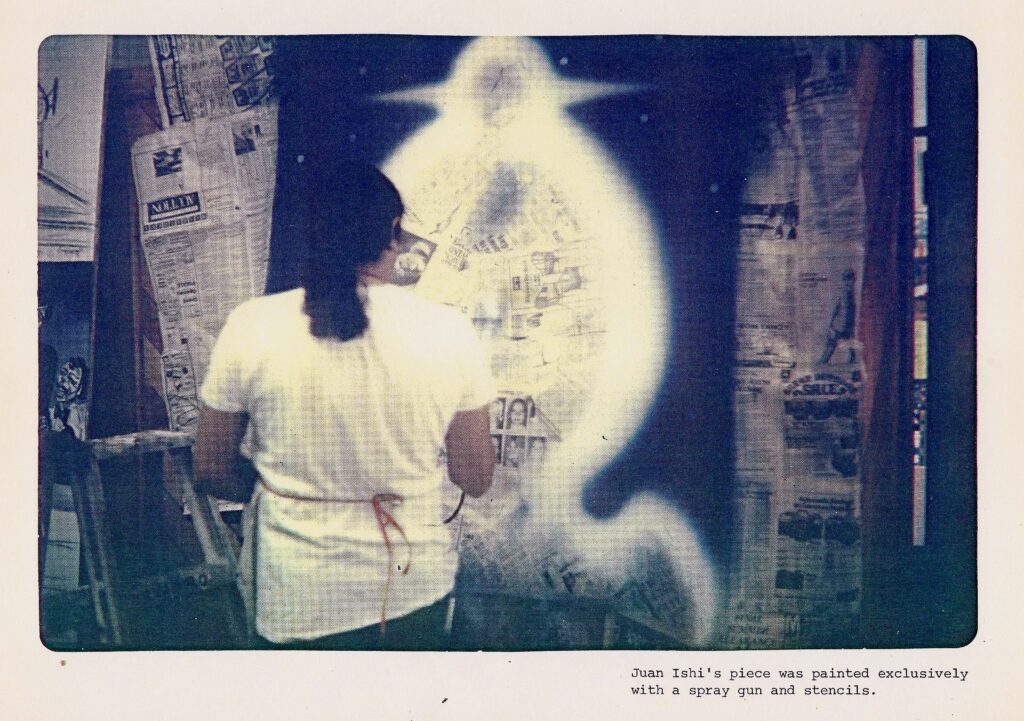

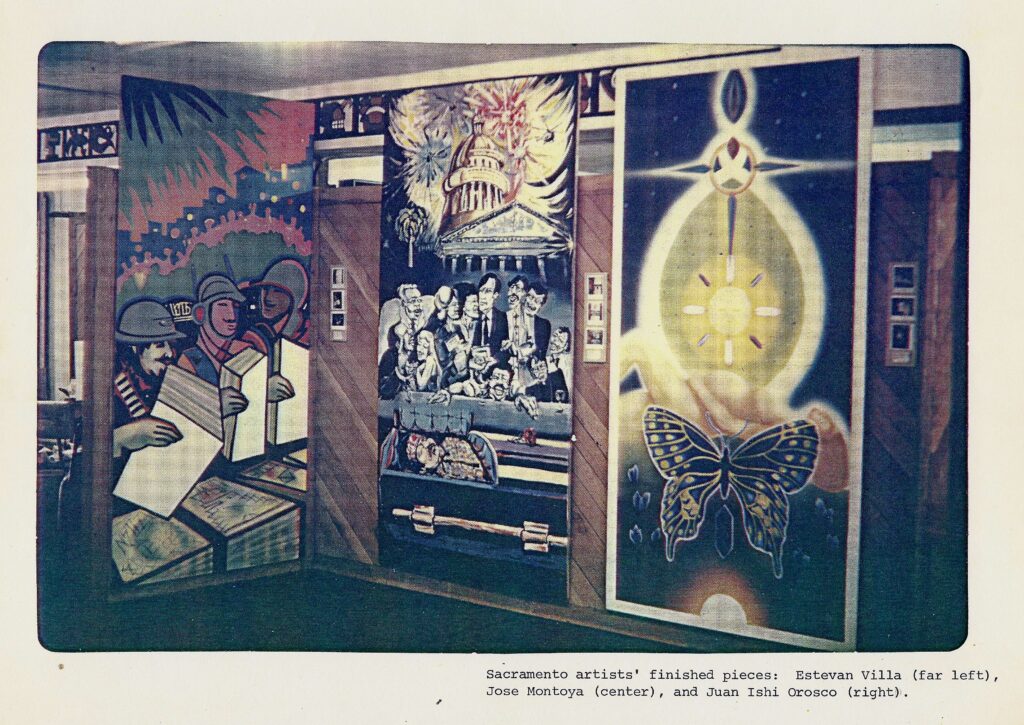

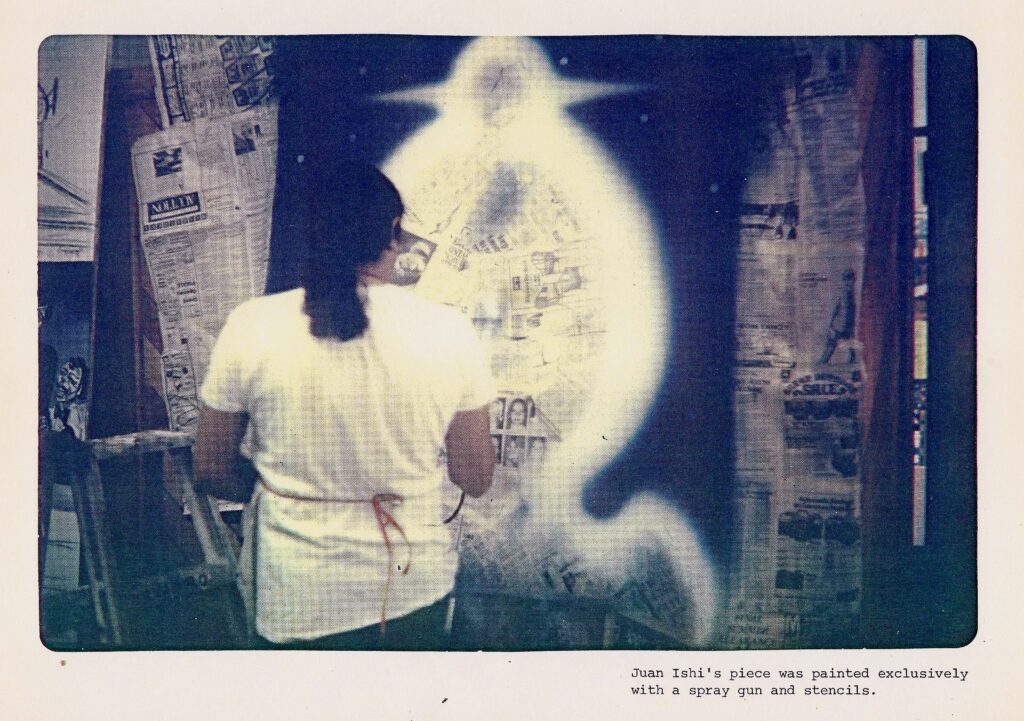

What these primary sources of art history reveal is that In Progress was planned as a traveling exhibition that physically moved across California to Chicana/o art galleries, community centers, and public spaces. The mural also expanded as it moved. On view at La Raza Galería Posada in Sacramento in the summer of 1982, In Progress acquired three additional panels created by Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) artists José Montoya, Juanishi Orosco, and Esteban Villa. These were shown along with several original panels when In Progress returned to San Francisco for exhibition at the Twenty-Fourth Street Fair in September 1982. In Progress next traveled to the SPARC Gallery in Venice, California, where additional panels were created and, in 1983, it was exhibited in San Diego.[39]

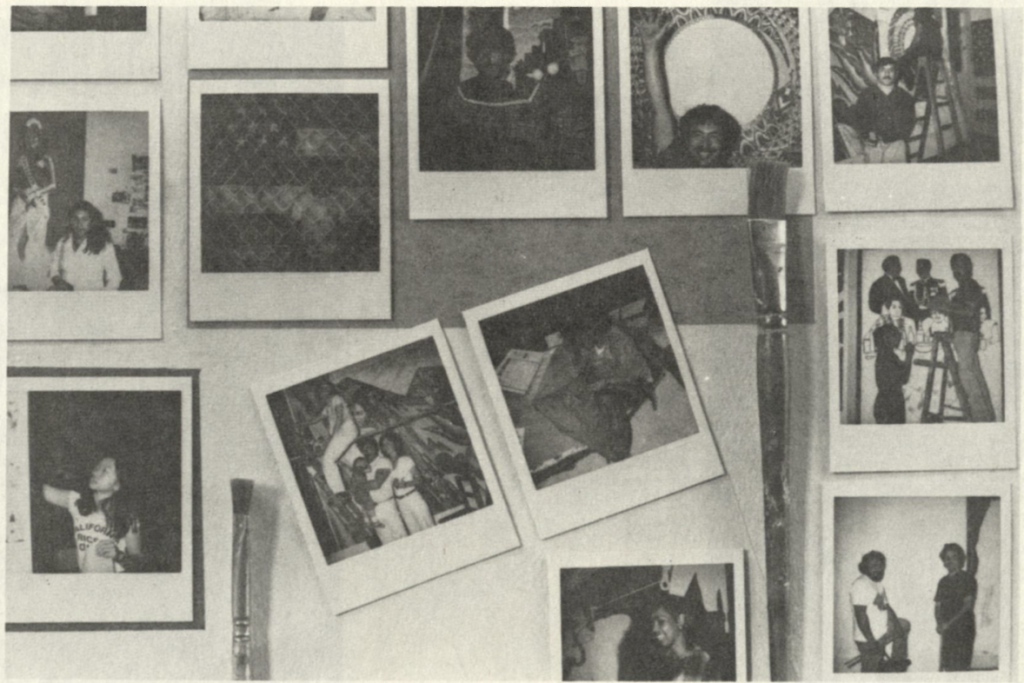

Key to its movement, circulation, and growth was the physical materials on which the panels for In Progress were created. The original panels were painted with oils and Politec acrylics and incorporated other media, like Polaroid photography in Yañez’s panel, which documented the process of the mural’s creation.[40] Drescher notes that only $1,000 was spent for the show as no foundations were “supportive of this communal effort” since they “appeared to think of the project as ‘entertainment,’ not art.”[41] The mural panels pictured in the exhibition catalogue (and available online through the Galería de la Raza collection at CEMA) suggest the artists painted on boards (perhaps plywood) or even large canvases.

More than likely, the In Progress artists painted on Masonite panels. A hardboard material developed in the early twentieth century, Masonite became a commonly used surface for painting and is found throughout modern American art history.[42] Certainly, the In Progress artists were aware of Masonite as a surface for modern painting. Juanishi Orosco, of the Royal Chicano Air Force, recalled using it for his panel when In Progress traveled to La Raza Galería Posada in Sacramento.[43] Like Rivera’s and Orozco’s transformations of mural painting through portability and different arrangements of the panels, the In Progress artists expanded the possibilities for muralism through their materials choices. Today, making art out of any material at hand resounds in the accessible and affordable materials used in contemporary art. Postmodern concepts of relational aesthetics and community art—as a broad category or field of contemporary art—are historically tied to the In Progress artists of the Bay Area.

Early in the catalogue essay for In Progress, Drescher forecasts that its “idea will someday be ‘borrowed’ and proclaimed as new and original, but the point is that as one part of a larger whole it attests to the complexity of In Progress.”[44] There are artistic processes that cannot be monetized by a capitalist system of cultural value because they are more than the sum of their parts; one of the immeasurable processes inherent to the In Progress mural pertains to the community it built by welcoming diverse audiences into an experience of being together in a space and collaborating on an idea.

In 2021, the art of building relationships continued in the relocation of Rivera’s Pan American Unity (1940) from City College of San Francisco to SFMOMA. As captured in the short film Diego Rivera: Moving a Masterpiece (2021), the process of moving Rivera’s epic mural brought different people together to realize an event as significant as the mural itself. From staff at SFMOMA to a local steward of Rivera’s mural, the team encompassed academics, scientists, and conservationists from the National Autonomous University of Mexico City (UNAM), the Consul General of Mexico in San Francisco, and City College personnel. This transnational dialogue also included local city workers and the expertise of fine art handlers when a caravan of diesel trucks moved the prolific fresco panels in the middle of the night across the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge and through a closed-off street in San Francisco to SFMOMA.[45] Placed prominently in the public-facing windows of the Roberts Family Gallery, Rivera’s mural tells a twenty-first century story about Pan American Unity—when local, institutional, and transnational actors came together to realize a shared vision and were transformed into a community.

Notes

- The photographs of In Progress mural panels from Galería de la Raza are available via the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives (CEMA) at UC Santa Barbara, http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf267nb24r/.

- The exhibition catalogue is available in seven libraries throughout the United States, according to its WorldCat entry: http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32714963.

- In this essay, I use “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)” as a term to encompass the multiracial communities, political coalitions, and artistic movements in the San Francisco Bay Area during the late twentieth century. While the term entered intellectual, political, and mainstream discourses in the twenty-first century, it is useful for addressing the interracial solidarity movements of the Bay Area during the sixties and seventies and for which the artists of the In Progress mural were involved. I also use the terms “Chicana/o” and “Chicano movement” to historically situate certain artists and events. I use “Latinx” to recognize the critical turn in the twenty-first century toward inclusion of all genders and sexualities of artists who identify as part of a broad interethnic group and/or create art deemed to be culturally specific to an ongoing diaspora of people in the Americas.

- “Archival traces” are part of an important scholarly discourse on recovering historical events, movements, and artists in Chicana/o and Latinx art histories and related fields. I am drawing on ideas discussed in Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Activism and Feminism in the Movement Era edited by Dionne Espinoza, María Eugenia Cotera, and Maylei Blackwell (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018); as well as María Eugenia Cotera, “‘Invisibility Is an Unnatural Disaster’: Feminist Archival Praxis after the Digital Turn,” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 4 (2015): 781–801; and The Silence of the Archive by David Thomas, Simon Fowler, and Valerie Johnson (Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2017).

- Timothy W. Drescher, Progress in Process (San Francisco: Galeria de la Raza/Studio

24; printed by La Raza Graphic Center, 1982). - Drescher, 4.

- Drescher, 5.

- Ella Maria Diaz, Flying Under the Radar with the Royal Chicano Air Force:

Mapping a Chicano/a Art History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017), 49. - Drescher, Progress in Process, 18.

- Karen Mary Davalos, Yolanda M. López (Los Angeles: Chicano Studies Research Center, 2008), 127.

- Davalos, 41–48, 95–96.

- Diaz, Flying Under the Radar, 123–24.

- Drescher, Progress in Process, 16. Drescher writes that a gallery visitor was upset by López’s interpretation of la Virgen de Guadalupe and they had a meaningful discussion resulting in the In Progress artists’ collective decision to add statements about their mural panels to the show. Controversy surrounding López’s larger Guadalupe series is well documented. See Davalos, Yolanda M. López.

- Hom (Nancy) papers, CEMA 46, UC Santa Barbara Special Research Collections,

www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z43c5/. - Drescher, Progress in Process, 18.

- “Hom, Nancy,” artasiamerica, accessed May 21, 2022, http://artasiamerica.org/artist/detail/342. See also “Guide to the Nancy Hom papers CEMA 46,” Department of Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z43c5/entire_text/.

- Lucy R. Lippard, Mixed Blessings: New Art in a Multicultural America (New York: Pantheon Books, 1990), 5. Lippard’s framing of the “mixed blessing” of the multicultural turn in late twentieth-century American art is more complex than I represent here as she grapples with the idea of aesthetic innovation via social exclusion.

- Drescher, Progress in Process, 4.

- I use relational aesthetics to describe the conceptual process inherent to the In Progress mural. Nicolas Bourriaud defined the term as a creative turn toward human relations, social contexts, and praxis in contemporary art exhibitions that decenter individual artists. See Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon, France: Les Presses du Réel, 2002), 14. Bourriaud claims that relational aesthetics refigures “meetings, encounters, events, various types of collaboration between people, games, festivals, and places of conviviality” as aesthetic objects—with traditional art objects like pictures and sculptures “regarded here merely as specific cases of a production of forms with something other than a simple aesthetic consumption in mind,” 28–29.

- Drescher, Progress in Process, 4.

- For more on the community mural movement and the political choices made by artists concerning collective valuation over individual ownership of murals, see Eva Sperling Cockcroft, John Pitman Weber, and James Cockcroft, Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement (1977; repr., Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998).

- Shifra Goldman, Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin

America and the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 165. - Cary Cordova, The Heart of the Mission: Latino Art and Politics in San Francisco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 118–19.

- MALA-F was founded in 1968 by Esteban Villa, Manuel Hernández-Trujillo, Malaquías Montoya, and Yañez, in Oakland. Their salon-style meetings included students of Quinto Sol at UC Berkeley as well as the editors of El Grito: A Journal of Contemporary Mexican-American Thought. See Diaz, Flying Under the Radar, 71. Established in 1967, El Grito was the “first national academic and literary Mexican American journal in the United States.” See Dennis López, “Good-Bye Revolution—Hello Cultural Mystique: Quinto Sol Publications and Chicano Literary Nationalism,” Melus 35, no. 3 (2010): 183–210. This foundational journal also published the first collection of the MALA-F’s visual art in its Spring 1969 issue. Issues of El Grito are available online and hosted by Northwestern University’s Open Door Archive: https://opendoor.northwestern.edu/archive/collections/show/15.

- Terezita Romo, Malaquias Montoya (Los Angeles: Chicano Studies Research

Center, 2011), 43, 45. - The “pan unity” motif of Rivera’s 1940 mural pertained to “Pan-Americanism,” an aesthetic “movement toward the social, economic, military, and political cooperation among the nations of the Americas.” See Anna Indych-López, “Mural Gambits: Mexican Muralism in the United States and the ‘Portable’ Fresco,” Art Bulletin 89, no. 2 (2007): 287–305. Art historian Indych-López adds that while the concept “was advanced primarily by government officials,” many intellectuals and artists like Rivera embraced it and “glorified an indigenous past in Mexico, which according to the logic of Pan-Americanism, came to be viewed as a common heritage for the entire continent,” 292. This top-down relationship to power, in terms of artistic representation, resonates in the critique of the reduction to “sameness” in the multiculturalism of art institutions and collectors. Through the relational process, the In Progress artists pushed back on the commodification of individual Black, Indigenous, and People of Color artists, which Drescher underscores in his point that unity between the artists was not about sameness but respect for each other’s differences.

- Indych-López, 288.

- Indych-López, 288.

- Rivera’s other two murals in San Francisco include Allegory of California (1930) at the Pacific Stock Exchange and Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees (1931) for the Sigmund and Rosalie Meyer Stern residence. See Indych-López, 288.

- SFMOMA, “Diego Rivera’s Largest Portable Mural, Pan American Unity, Opens at SFMOMA on June 28, 2021,” released June 24, 2021, https://www.sfmoma.org/press-release/diego-rivera-pan-american-unity/.

- Indych-López, “Mural Gambits,” 287.

- Indych-López, 288.

- In Progress, for example, involved artists Patricia Rodriguez, Ray Patlán, and Miranda Bergman, who created murals in Balmy Alley. In 1984, Rodriguez and Patlán formed PLACA, which financed and spurred a new era of Balmy Alley murals that they financed with a local grant partner. See Guisela Latorre, Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008), 165.

- Indych-López, “Mural Gambits,” 287.

- Indych-López, 299.

- Indych-López, 299–300.

- Indych-López, 300.

- Exploring the possibilities of vanished and destroyed murals in Chicana/o art history since the sixties, Karen Mary Davalos examines artist Sandra de la Loza’s Action Portraits (2011) as groundbreaking artwork that merges historical and archival methods with creative expression; de la Loza offers a (re)presentation of seventies Chicana/o murals by fusing the materiality of wall painting with the demateriality of digital tools. Part of her larger exhibition Mural Remix (2011), de la Loza had contemporary East Los Angeles muralists filmed as they painted themselves (using green screen technology) with samples of designs taken from color slides of the Nancy Tovar Murals of East Los Angeles Collection. The recordings were then projected on the wall of a gallery in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2011. See Karen Mary Davalos, Chicana/o Remix: Art and Errata since the Sixties (New York: NYU Press, 2017).

- Drescher, Progress in Process, 35.

- Drescher, 17, 33.

- Drescher, 10.

- Kristen Zohn Miller, What Lies Beneath: Masonite and American Art of the 20th Century (Laurel, MS: Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, 2019). Exhibition catalogue for show held August 13–November 17, 2019, https://www.lrma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/199683-lrmaBooklet_d5-1.pdf.

- Juanishi Orosco, conversation with author, January 13, 2023. Also, see an online note for Orosco’s mural panel, Amor Indio, one of two that he created for a subsequent RCAF mural shown at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. It lists “Politec mural paints on Masonite panels.” This slide is part of the Royal Chicano Air Force (CEMA 8) collection: https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/hb6f59p3h5/. Viewers may also note a discrepancy in the slide annotation. In Progress was shown at La Raza Galería Posada in 1982, and not the Crocker Art Museum. The RCAF created a multi-panel mural titled Crystallization of the Chicano Myth after In Progress, which was on view at the Crocker Art Museum the following year.

- Drescher, Progress in Process, 6.

- NBC Bay Area, “Diego Rivera: Moving a Masterpiece,” September 13, 2021, YouTube video, 24:01, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r6K2YTyN4jg.