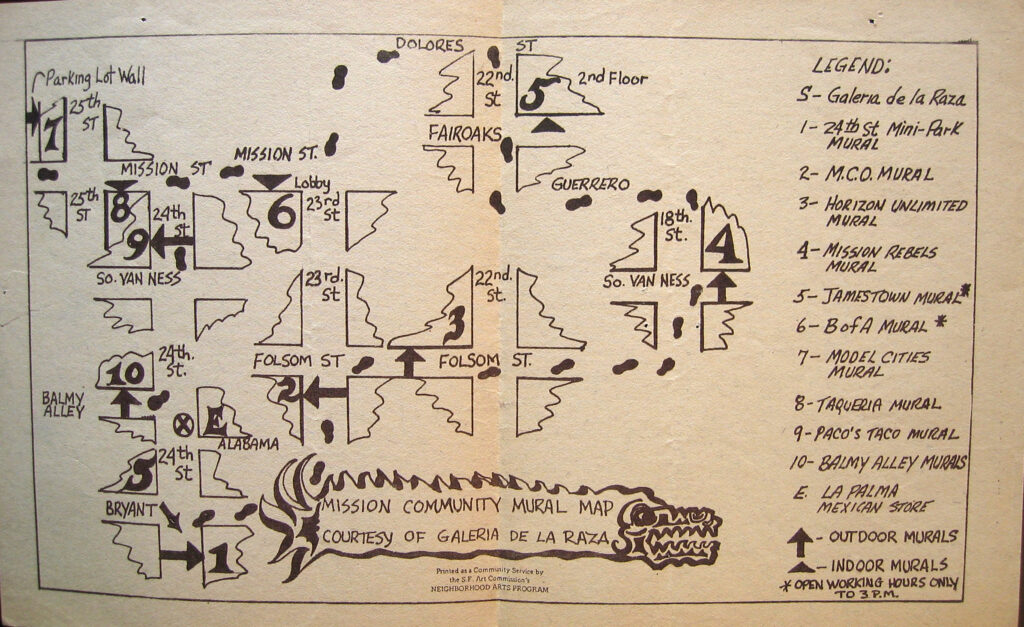

In the mid-1970s, Galería de la Raza distributed a Mission Community Mural Map that guided viewers to key murals in San Francisco’s Mission District (fig. 1). The density of murals in the neighborhood was impressive — and sudden. All of the murals listed in the map were created between 1972 and 1974. Sadly, the artist did not sign this cheeky portrayal of city blocks as Aztec pyramids, situated above a plumed serpent, presumably Quetzalcoatl, as it motored through the streets with the map title in its belly. For this humorous walking tour, the map reimagined the Mission through the lens of Aztec codices and illustrated the ways this emerging art form blended ancient and contemporary Mesoamerican aesthetics.

The map presented these ten mural sites as important destinations. The artist used shoe prints as guidance, a map-making practice that also paid homage to footprints in Aztec codices and Indigenous maps. Alex Hidalgo’s research on Indigenous maps from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries emphasizes the power of maps not just as tools to navigate and allocate land but as instruments to interpret space and foster new epistemologies. He writes, “The footprint emerged in the sixteenth century as the most enduring element of mapmaking. Feet used in pre-Columbian codices symbolized journeys, a reminder that a great lord once embarked on a quest for marriage or to wage war in an effort to preserve a lineage or to expand a domain.”[1]

Galería de la Raza, marked with an S (perhaps invoking the serpentine Quetzalcoatl), served as a space to foster new epistemologies and aesthetics in response to the limited opportunities afforded artists of color in traditional galleries and museums. With the leadership of codirectors Ralph Maradiaga and René Yañez, Galería de la Raza often helped coordinate and raise funds for local murals.[2] The mural map, possibly indebted to the artistry of Maradiaga, whose work often turned to ancient iconographies for inspiration, gave visibility to a growing cadre of artist-activists redefining local spaces and the meaning of art.[3]

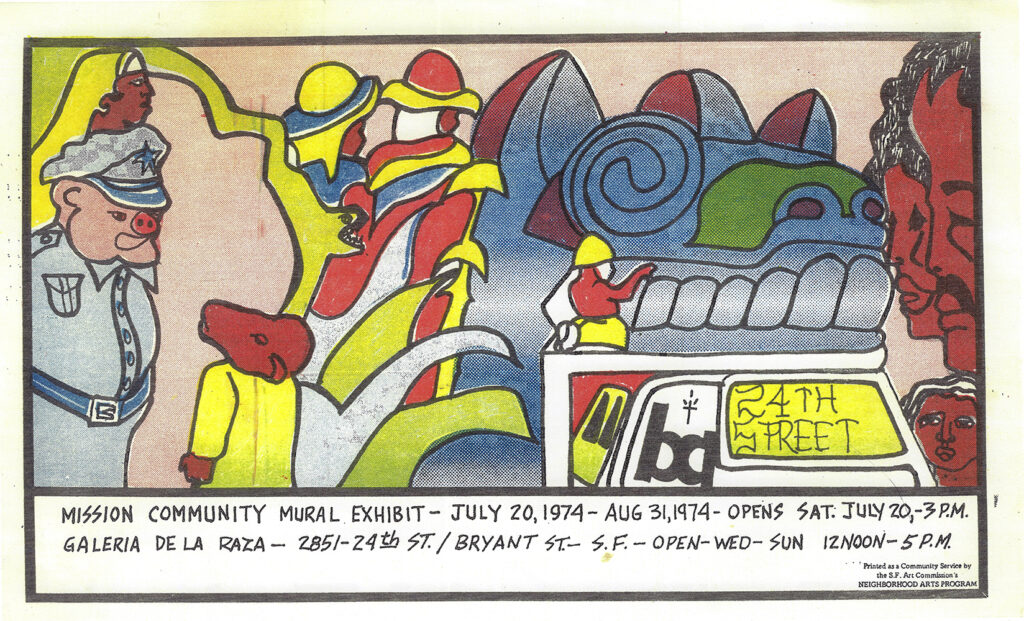

More than likely, Galería de la Raza produced the map to accompany its mural exhibition in the summer of 1974 (fig. 2). The map encouraged a circular path from 24th Street to Folsom, 18th to Guerrero, 22nd to Dolores, 23rd to Mission, and finally back to Galería de la Raza at the corner of Bryant and 24th Streets. Dispensing with the use of scale or a compass, the map’s shoe prints presented a visually compact path, while the trail actually encompassed three miles of densely populated urban space. The map presented the murals as separate entities, as well as part of an interrelated journey expressive of the Mission.

The map spotlighted key murals in the Mission but could not include all the murals springing up all over the city, including in the Haight, Fillmore, Hunter’s Point, and Chinatown neighborhoods, nor all the talented muralists, including Dewey Crumpler, Jane Norling, and Jim Dong. In fact, by the time these early murals in the Mission appeared, the community mural movement had already made a significant imprint in the Bay Area and across the country in urban and rural spaces.[4] Thus, the city’s mural movement did not begin in the Mission, but the neighborhood became synonymous with murals.

Those following Galería de la Raza’s self-guided tour quickly discovered that the serpent figure on their map served as a humorous preview of their first stop. Listed only as the 24th Street Mini-Park Mural, it was also known as Quetzalcoatl (fig. 3).

Completed in the summer of 1974 by Michael Ríos, Tony Machado, and Richard Montez, the mural featured a massive green-feathered serpent body spanning a thirty-two-foot wall on the east side of the park.[5] The astonishing figure surfed through an Indigenous village, incorporating images of people gathering water and food, carving and painting stone, playing music, befriending jaguars, turning mechanical levers, and taking counsel upon an altarlike platform. The imagery celebrated the scholarship and accomplishments of Mesoamerica, affirming the value of this ancestry for children enjoying the new playground. This monumental work was the first of several by this trio of artists to grace the walls of the recently created mini park.[6] The park’s muralization represented a profound visual transformation underway as muralists sought every opportunity to redefine the color and look of the neighborhood.

The artistry of the murals cast the Mission in a new light. A reporter writing in 1976 offered a backhanded compliment, declaring, “In a city full of world-famous sights, the corner of Mission and 24th streets is seldom, if ever, mentioned in the guide books. But starting at that intersection is a remarkable tour of neighborhood murals.”[7] Murals provoked positive attention for a neighborhood that struggled to be seen.

The Mission Community Mural Map (and Proyecto Mission Murals) centers the Mission as a dynamic and important site for mural creation, but drawing borders can also limit the ability to see the larger contexts and the movement of muralists around the city and the globe. Many traveled and trained well beyond the barrio’s borders.[8] For instance, Ríos and Graciela Carrillo traveled to Europe, while Jesus “Chuy” Campusano, Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez, and Irene Pérez traveled to Mexico.[9] Consuelo Méndez migrated to the Bay Area from Venezuela. The zeitgeist was internationalist in scope, even if the work appeared site specific.

This article uses this mural map as a frame to examine the rich history and extraordinary talent that emerged in the Mission between 1971 and 1974. Piecing together the history of these early murals means turning to a wide variety of sources, while also accepting that some images and stories are lost. Most of these murals no longer exist, except in photographs. Thankfully, scholar-photographer Tim Drescher created an unparalleled archive of mural images. Proyecto Mission Murals is indebted to his and other documentary efforts that enable later generations to see these murals in spite of urban redevelopment, social change, and harsh rain and winds. Of course, this also means recognizing the power of photographs to frame contemporary interpretations of these works. The images of some murals are incomplete or nonexistent, leaving us to wonder what might have existed outside the frame. Acknowledging the limits of the archive, this virtual tour maps the ways these early murals launched spaces for others to flourish for decades to come.

Into the Streets

Multiple factors spurred the rise of community murals in the late sixties and early seventies. Legislation, especially the 1964 Civil Rights Act, facilitated access to education in the arts for youth and adults of color. Several of the Mission muralists first met at the San Francisco Art Institute, thanks to newly available scholarships. While they benefited from access to professional training and mentors, they also struggled against the curriculum, which emphasized Eurocentric aesthetics.[10] Artists of color pushed back on narrow white supremacist interpretations of art, while also having to heed the gatekeeping of schools, sgalleries, and museums, which could limit their careers. They turned to making murals in the streets to circumvent the limitations of the art world, while also publicly displaying their aesthetic talents and cultural histories.

Public battles over arts funding escalated in San Francisco in the late sixties, when corporate magnate Harold Zellerbach lobbied for the creation of a multimillion-dollar performing arts center modeled on New York’s Lincoln Center. Heir to a fortune in the paper industry, Zellerbach had dedicated years of service to the city’s arts commission, symphony, opera, ballet, and fine arts museums. However, Zellerbach’s critics decried his “Manhattanization” of the city, describing his spending on elite arts institutions as a “subsidy for the rich,” while neighborhoods outside the city center received nothing.[11] Responding to the uproar, Zellerbach proved “instrumental in getting the Neighborhood Arts Program created and financed,” though he also shaped its direction under the San Francisco Arts Commission.[12] While the Neighborhood Arts Program (NAP) struggled for autonomy, it nonetheless radically amplified access to arts and funds across the city.

The emergence of NAP, the Supplemental Employment and Training Program (STEP), and the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) of 1973 played important roles in mural sponsorship.[13] When Galería de la Raza struggled against an eviction at its first location on 14th Street for “failure to pay back rent,” the artists looked outside the gallery setting for artistic opportunities. They applied for STEP and NAP funds, which helped seed money for a wave of murals that continued well after the gallery had found its next home on 24th and Bryant.[14] Through NAP, Yañez recalled, “I had a budget to commission people to do murals. Spain was actually the first artist to do a mural in the Mission. After that Robert Crumb did one (figs. 4 and 5).”[15]

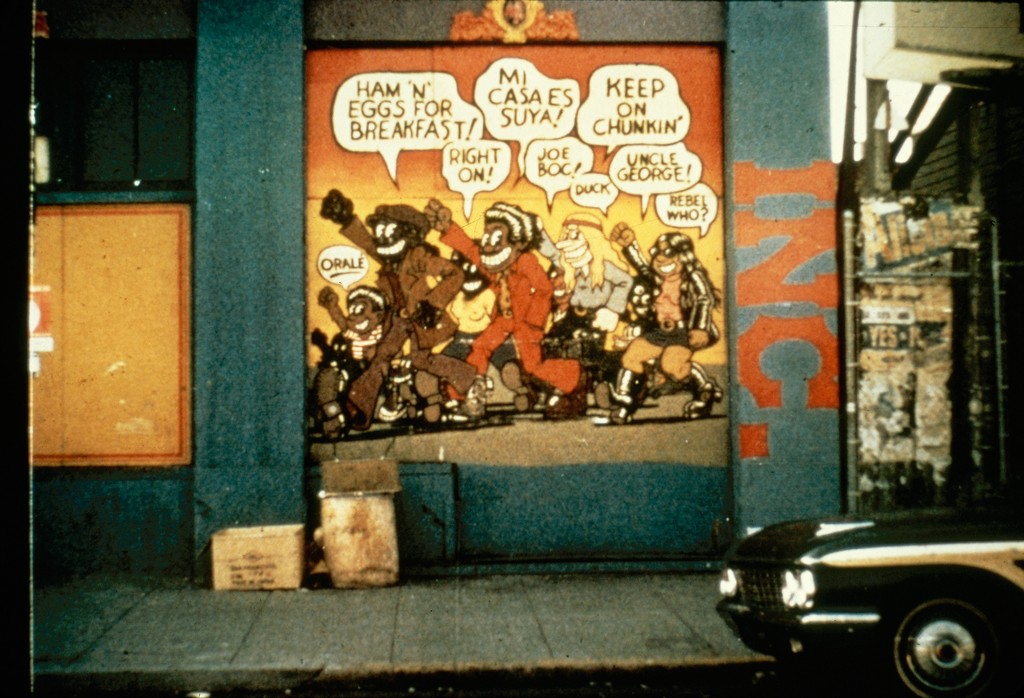

While access to new funding opportunities helped cover supplies, compensation for artists was modest, if anything at all. Crumb volunteered his time for the Mission Rebels mural, while Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez received a small stipend of three hundred dollars for six months of work to create the Horizons Unlimited mural.[16] Artists often had to make do with very little when producing art for the community. Their work served the nonprofit mission of their patrons, Mission Rebels and Horizons Unlimited, both of which developed as programs to prevent youth from dropping out of school and joining gangs, while also creating job training and placement. However, the nonprofits differed significantly in their ethos, perhaps owing to Horizons Unlimited developing out of federal programming, while Mission Rebels emerged as a grassroots organization. Both organizations benefited from increased funding to help inner city youth escape poverty.[17] Thus, Rodriguez and Crumb drew on their expertise as comic book artists, using frames and word balloons to appeal to the youth visiting the buildings.

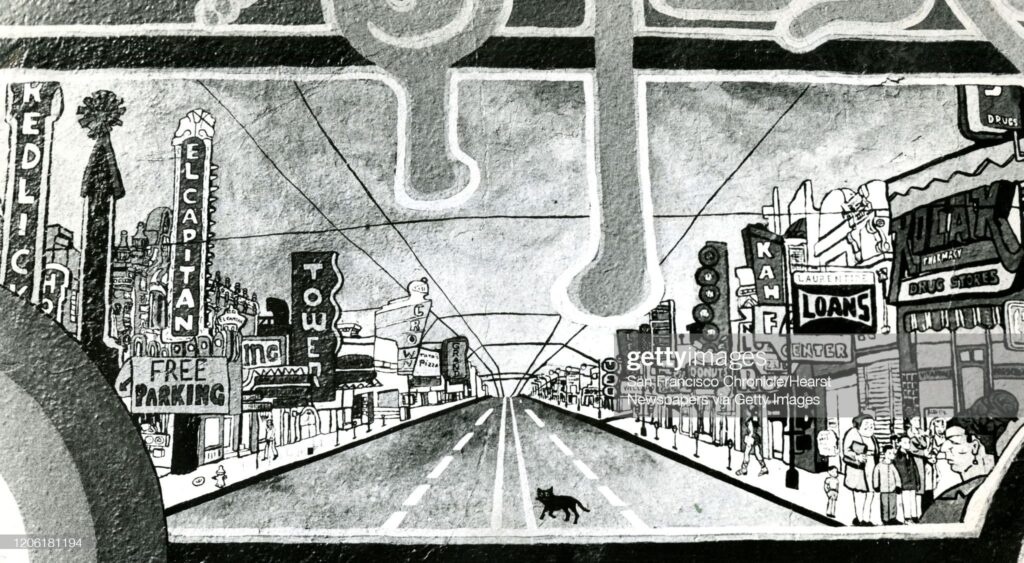

Spain Rodriguez’s project took more time because of his commitment to detail, animating a detailed portrait of the Mission in four comic-book frames (see fig. 4). He incorporated youth in the project, leading to the creation of multiple interior murals with a variety of aesthetics and interests. Crumb also invoked comic stylings but kept the iconography and detail much simpler. For the exterior of the Mission Rebels building, he created an enlarged comic panel, which featured a line of multiracial youth pumping fists in the air, but rather than shouting protest statements, he filled their word balloons with silly comments, including “Ham ‘n’ Eggs for Breakfast!” and “Keep on Chunkin’” (see fig. 5).[18] Rodriguez started first, but Crumb knocked out the Mission Rebels mural very quickly; both murals reached completion around the same time in early 1972.[19]

These initial murals helped popularize a comic style. As Ríos recalled, “I wanted to do this big cartoon strip up there styled after Robert Crumb’s work.”[20] For Ríos, the power of murals emerged with his first commission, the MCO mural, also known as Rat Race, which he completed in June 1972 (fig. 6).

His patron, the Mission Coalition Organization (MCO), was a major actor in the Mission in the late sixties. As Tomás Summers Sandoval writes, “At its height, the MCO was an institutional force, recognized as the ‘voice’ of the district in political circles and authorized as the local agent of Model Cities — a 1966 federally funded ‘community development’ program mandating ‘citizen participation.’”[21] According to Ríos, since the MCO had been helping Galería de la Raza with its rent, the organization asked the gallery to provide an artist to help repaint one of their walls. Ríos not only volunteered but proposed a vision far beyond what the MCO had requested. He did not receive any payment for his labor, but the MCO did cover his paint.[22] As he recalled:

But I said, well, man, instead of doing just a straight paint job, I think I could see a big cartoon strip on this wall indicating all the different little activities that go on in the Mission and city life. Because I have a sense of humor. I always thought that certain kind of city life, it’s like a rat race sometimes. It’s a rat race. And people have to just scurry like little ratonas to make ends meet and get through life. So that’s what I did. I did this big cartoon. And the reason I had done it as a cartoon thing is because there was a school, a little elementary school, across the way. And kids used to walk by. I said, I’m going to do this to entertain the kids.[23]

The cartoonish imagery openly appealed to children while enabling Ríos to critique bureaucratic city life. Ríos bluntly portrayed police as pigs, invoking his frustration with an unjust system. He explained at the time, “Well, personally, I’ve been bugged a lot by the cops. I’ve been stopped for nothing. Kids get busted for nothing. Also, as far as I know, there are more police here in the Mission than anywhere in the city.”[24] Ríos’s frustration with community policing reflected the spirit of the location, which also housed Neighborhood Legal Aid, an organization dedicated to providing affordable and accessible legal services.[25]

Intentionally provocative, the mural spurred public reaction. According to Ríos, “Some cops came by and threw acid on the jail and court scenes about a month after completion.”[26] Passionate responses prompted even more attention, leading news anchor Walter Cronkite to discuss the mural on the national CBS Evening News. As Ríos recollected, “I immediately realized the power of murals.”[27] While many residents responded positively to the presence of murals, some controversial themes inspired anger and defacement. Tensions over the content of the MCO mural likely contributed to its short life, at least in comparison to subsequent murals that Ríos created.

Ríos continued to speak out through murals, though different contexts may have facilitated longer life spans. In 1974 he used his mural experience to assist Campusano’s vision for a monumental ninety-foot mural, Homage to Siqueiros, inside the Bank of America. The mural illustrated a variety of everyday scenes, including images of children deboarding school buses, teens graduating from Mission High School, and customers waiting at the bank window, while also not so subtly critiquing capitalism, placing their iconography at odds with their patron. Indeed, the central figure of the mural depicted an agricultural worker extending his fist at the viewer as another man opened a text to César Chávez’s statement, “Our sweat and our blood have fallen on this land to make other men rich” (fig. 7).

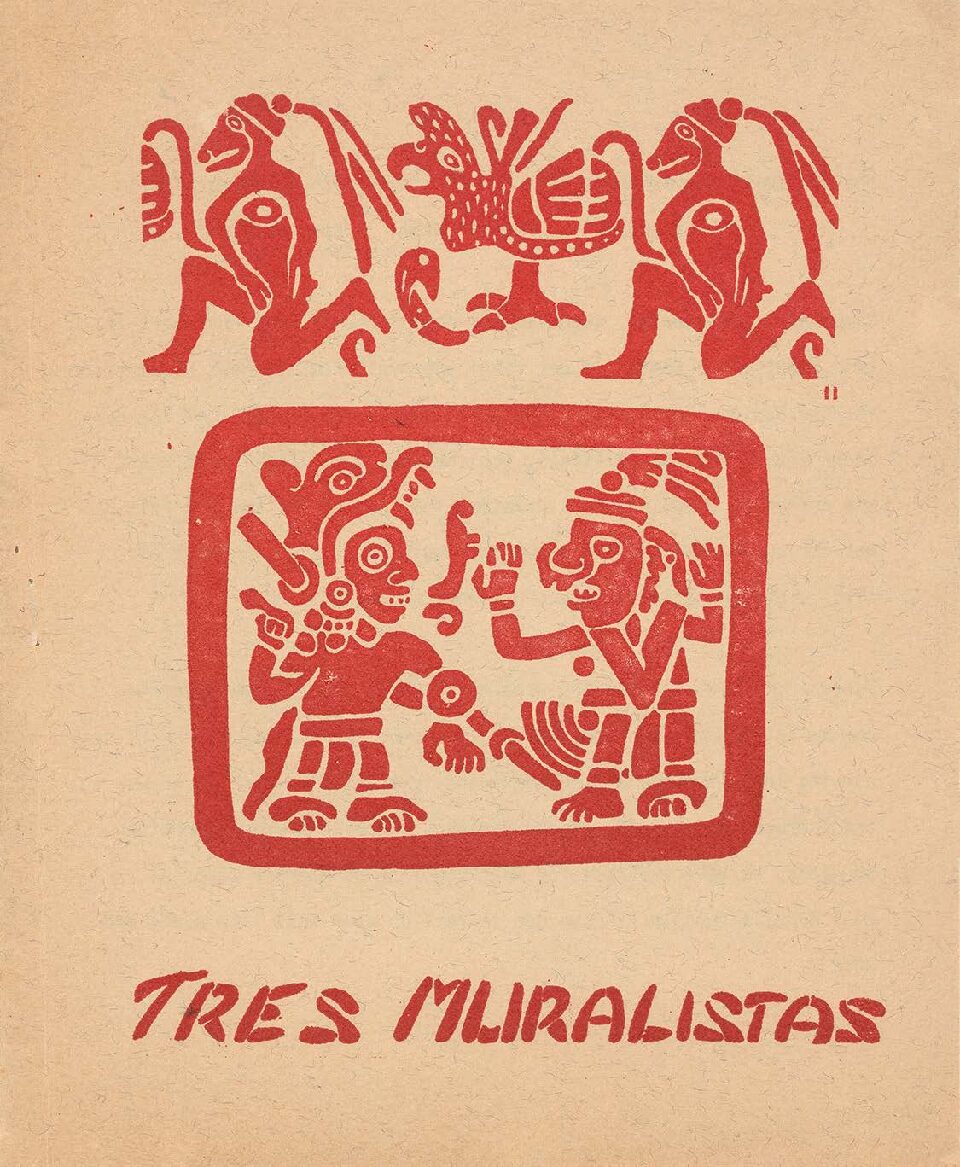

Campusano, Ríos, and Cortazar drew on the tradition of Mexican muralists, particularly David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco, to speak out for the underdog. With support from San Francisco resident Emmy Lou Packard, who served as an assistant to Rivera, the muralists claimed space inside the bank to articulate a vehement visual critique of capitalism. For the mural’s completion, they published a small booklet to circulate at the opening, which detailed their struggles with the bank over the mural iconography (fig. 8).

In The Heart of the Mission, I wrote at length about the creation of Homage to Siqueiros and the artists’ efforts to produce a “media spectacle designed to undermine their corporate sponsor.”[28] Thankfully, the Bank opted to insure the mural instead of destroying it, which allowed it to survive significantly longer than most murals of this era.

Gendered Geographies

Notably, the first major mural commissions in the Mission all went to male artists. The men rarely recognized the exclusivity of their commissions, but the women artists reckoned with it daily. As men and women worked in separate spheres, the murals took shape in gendered spaces. While the men dominated the mini park, women established Balmy Alley. Seeing these divisions is illustrative of the gendered inequalities that also shaped the Mission mural movement.

Those that followed the Galería de la Raza mural walking tour had to make sense of the art out of chronological order, as the path started with a later mural and ended with some of the earliest creations. The map’s presentation also may have reflected gendered priorities, as the work of male artists came first, followed by the work of women artists, and then children. Both codirectors of the Galería de la Raza, Maradiaga and Yañez, expressed support for women artists, but the institution often prioritized men. Fifteen or twenty Latino male artists claimed founding the gallery in 1970 as a creative space to work apart from the discrimination of the mainstream art world, but they failed to see the absence of female founding members as emblematic of their bias.[29]

Women artists actively worked in the community, but they regularly struggled with implicit and outright exclusions and often worked separately. In 1972, Patricia Rodriguez had a job placing artists in the community. A priest from the Jamestown Community Center presented the possibility of doing a mural at their school. Rodriguez recalled, “When he offered me this mural process, I came back very excited, and I talked to Consuelo Méndez, I talked to Graciela Carrillo, and I said, ‘you know what, we can do something more exciting. Let’s just go and do this mural. Would you join me?’ . . . And they all got so excited, and we ended up at my house, and that night we had wine and cheese and we celebrated and we started drawing” (fig. 9).[30]

Excited about the project’s potential, Rodriguez invited others to join. With Yañez’s help recruiting, the project expanded to include Campusano, Guzmán, Ríos, and his brother Tom Ríos. However, Rodriguez quickly observed how important it was for the men to maintain separate wall spaces: “it helped the guys in particular because they didn’t have to share the space [laughs]. It was very important!”[31] She elaborated:

Well, the male artists had always felt that they were above us and that they were better than us, and that they were the artists and we weren’t. And so, that’s what got us all hot and ready to go, and we said, “oh, you think you’re the artist? You don’t want us to paint with you? Oh, that’s good, that’s all right; you don’t want us to paint with you.” We would ask them, “can we do this mural with you?” Especially after the Jamestown, because, you know, I was the one that actually got it going. And so, “Oh, no, no, you guys can’t paint with us, but I’m Diego Rivera and you can be my assistant.” And we said, “well, you know what to do with that one.”[32]

Women encountered resistance not just with their peers, but with record keepers. When Alan Barnett produced his expansive tome Community Murals, he focused significantly more on the male artists that participated in the Jamestown mural project.[33] These encounters contributed to gendered mural geographies and exclusionary histories: women worked separately on several murals, while men teamed together and dominated other spaces.

The first murals in Balmy Alley started with the artistic imaginations of women and children, thanks to the leadership of Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez and Las Mujeres Muralistas. Galaviz founded 24th Street Place as a community education center in the early seventies. As she recalled, “a lot of children, multilingual, bilingual children, primarily Spanish-speaking children, were being diagnosed of having severe learning disabilities. We weren’t going to accept that, and I said, that can’t be possible.”[34] Galaviz’s recollections point to how segregated San Francisco public schools were at the time.[35] While bilingual education served a fundamental need, school districts often used it as a tool to funnel Spanish-speaking children into separate vocational or technical tracks, preventing students from accessing academic achievements.[36] Galaviz turned to educating neighborhood youth as a way of responding to inequities in the public school system and sharing her expertise as an artist. She prioritized creating educational resources and activities for children, including tutoring, music, dance, theater, and art classes.

Galaviz envisioned painting Balmy Alley as a way to engage children in the arts while also responding to unsafe conditions. The 24th Street Place center stood almost directly across from Balmy Alley, a one-block street connecting busy 24th Street to Garfield Square, a communal green space and public pool, and to the Bernal Heights public housing project. However, the alley also felt unsafe. As she elaborated, “Our kids, many of our children, came from the projects on the other side of Garfield Park and it was a hard, hard place for them.”[37] Children in the neighborhood faced precarious conditions, both in terms of safety and access to education. For Galaviz, “The whole goal of [painting Balmy Alley] was to make it a place of safety and a place for families to walk up and down, much like that experience I had in Mexico, where the Plaza was a safe place for families to congregate, to meet, and to be.”[38] She orchestrated the first major painting of Balmy Alley as a children’s mural project in the summer of 1972 (fig. 10).

Muralists reached out to children through their images and by including youth in the mural-making process. Community organizers advocated for the academic and artistic possibilities of community youth in a neighborhood struggling with poorly performing schools, substandard housing, and poverty. Barnett described how Susan Cervantes “got her start by helping with the youngsters,” though this observation also minimized her extensive experience with several mural projects.[39] Patricia Rodriguez recalled how Cervantes brought together the work of Carrillo and Méndez when they collaborated on Para el Mercado: “They worked in their own styles on separate sides of the mural, which looked divided but at the same time found consistency in its colors because Graciela invited Susan Kelk Cervantes to help paint with the group and design the color scheme for the mural.”[40] Cervantes excelled at giving mural projects cohesion through her sense of color and collaboration. In 1977 she and her partner Luis Cervantes cofounded Precita Eyes, a resource and training center for mural making, which subsequently launched hundreds of murals in San Francisco.

Women muralists built spaces for themselves because many of the men failed to consider inclusion or to value what they had to say. Rodriguez and Carrillo lived just a few steps down the alley from the 24th Street Place mural at 54 Balmy Alley. They asked a neighbor for permission to paint on the garage across from their building “to see if we could collaborate as muralists and draw large-scale designs” (fig. 11).[41]

Rodriguez reported that men and women teased them and dismissed their experimental work, except for Maradiaga, who acted as “our only constant source of support.”[42] Rodriguez credits him with suggesting the name “Las Mujeres Muralistas” for the collective.[43]

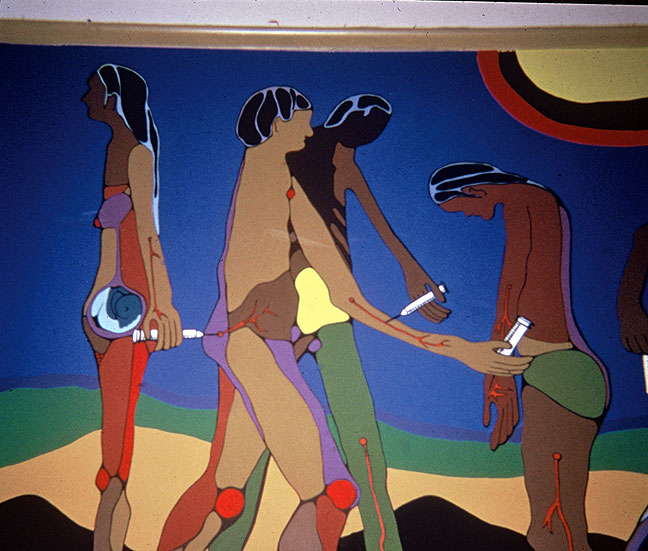

Alternately, even expressions of support could feel patriarchal and domineering rather than helpful. Pérez recalled how fellow artist Ríos helped her to pursue art school, but she also recalled his call for darker colors and images: “Mike Ríos wanted us to paint images with women chained up. We said no, we’re not chained up anymore. We’re not painting that.”[44] Pérez preferred to represent liberation differently. Not long after Rodriguez and Carrillo completed their Balmy Alley mural, Pérez added Flute Players at the other end of the street.[45] Pérez initially imagined her first mural as a dual image of herself (figs. 12 and 13). As she described years later, “I started to get into music, and I painted myself as two people facing two different directions playing a flute.”[46] Thus, the initial mural presents an image of self-contemplation, poised to head in different directions.

Years later, upon the quincentenary celebrations marking five hundred years since the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492, she returned to restore her first mural but reimagined the two figures as herself and her partner Catalina. She changed the hairstyles, clothes, and colors to more emphatically differentiate the two female figures. Far more open about being a lesbian than she had been in the seventies, she transformed the mural into an overt expression of queer love and Indigenous resistance.[47]

With a touch of humor, Pérez added a glib new title to the mural, “Coyolxauhqui Has Something to Say,” pushing back on chauvinism, heteronormativity, and colonialism (see fig. 13). Pérez recalled learning about Coyolxauhqui while visiting Mexico City in the late seventies, around the time an excavation at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan unearthed a monumental volcanic stone image depicting the goddess’s violent death.[48] Spurred by her siblings, Coyolxauhqui became enraged by her mother Coatlicue’s mysterious pregnancy. Intending to kill her mother, she was stopped by the birth of her brother, Huitzilopochtli, who emerged from their mother’s belly fully grown. Immediately, Huitzilopochtli decapitated and dismembered his sister and threw her body down the mountain.[49] William Barnes writes, “This same fate then awaited captured warriors of rebellious provinces or those from polities who declined to submit to Aztec hegemony.”[50] The goddess’s fate warned others not to rebel or they would face similar consequences.

For Pérez and many Chicana feminists, the story of Coyolxauhqui also represented centuries of patriarchal violence against women. As Pérez recalled, “it took me a long time to figure out what to do with Coyolxauhqui because she was all broken up, cut up, and thrown down the pyramid, which I think was the beginning of male chauvinism or whatever, the patriarch in our culture and society—well, in our culture.”[51] Pérez not only spoke back to this ideology by incorporating a relatively intact Coyolxauhqui into the mural, recognizable by her headdress and ear spools, but she also empowered her with a voice pronouncing in red letters: “500 AÑOS DE RESISTENCIA INDIA / 500 YEARS OF NATIVE SURVIVAL, 1492–1992.” The cacti at both edges of the mural also spoke to native resistance. In revisiting the mural, Pérez found a more vocal expression of herself, as well as a space of advocacy for residents facing the violence of historic and contemporary displacement.

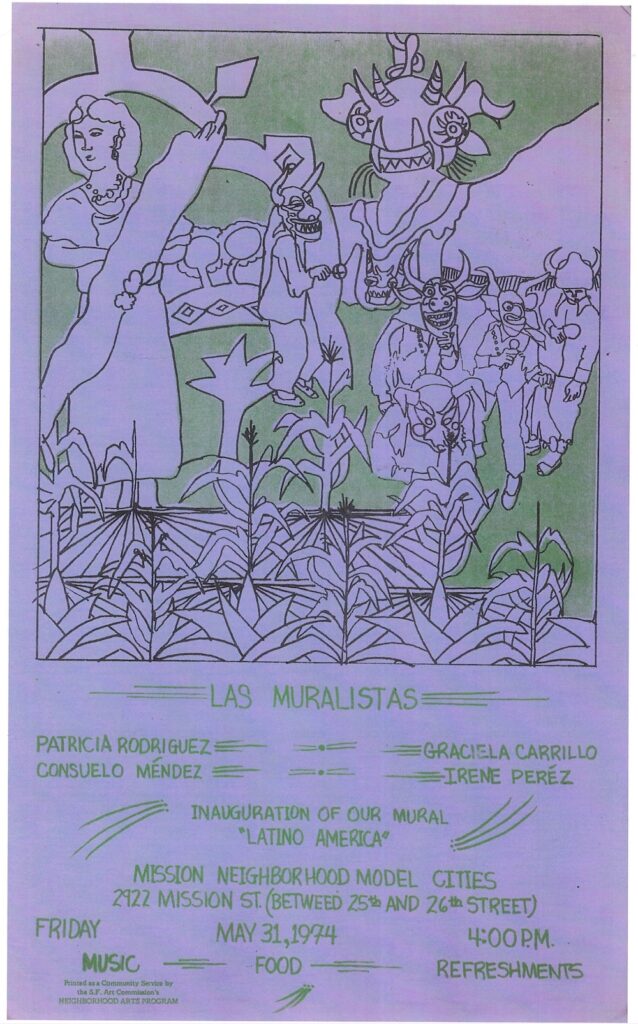

Balmy Alley served as an important alternative space for women and youth to train as muralists. Painting there prompted the Mujeres Muralistas to pursue more mural projects together, including Jamestown and Latino America, which I have written about at length in The Heart of the Mission, and which Terezita Romo writes about for Proyecto Mission Murals here. While Latino America represented a major commission and a monumental work for Mujeres Muralistas, it also was potentially gendered in that their patron, Mission Model Cities, requested the mural for a childcare center.

Murals often reflected location and patronage in their content as well as their commitment to community interests. Méndez declared in 1975, “It is very important for us to be conscious of the community where the murals are to be and the people of that community. The murals have to be a part of that community. Murals are a means to express the ideas that we have about many things and, most important of all, to carry out through images the ideas that I have about politics; that is, my ideas about how things should be. To show, through those images, the problems and injustices I see in the world right now and to try and present our people some solutions to those problems.”[52]

The artists always saw their work in relationship to the community, and likewise, the community recognized the importance of celebrating this art. The artists initiated the practice of mural receptions to celebrate the completion of these major projects. They invited the community with posters like this invitation to celebrate Latino America (fig. 14).

This precious poster is helpful in documenting the name the artists imagined originally for the mural, as it has undergone many name variations since its completion, including Latinoamérica and Panamerica. I previously noted that “Latino America without the accent maximizes the double meaning of the work, suggesting that Latinos in the United States are reinventing America as a nation as well as articulating a larger kinship to the Américas.”[53] Proyecto Mission Murals defers to Latino America as the original title for the work, but there is a long history of murals with multiple titles that encourage diverse interpretations. In these early years, muralists rarely incorporated a title into the mural itself, which often meant that murals existed with many names.

Even when more formal titles existed, murals as site-specific creations often became synonymous with their locations. For instance, while the Mujeres Muralistas adopted Para el Mercado as their mural title, as evidenced in their inauguration poster, others often referred to their work simply as the Paco’s Tacos mural (fig. 15).

At the time, Paco’s Tacos owner Joseph Bonilla was engaged in a legal effort to prevent a McDonald’s franchise from locating at the corner of 24th and Mission.[54] Bonilla commissioned Méndez and Carrillo to bring visibility and curry support for his situation. However, as one reporter described, “Aware of the proprietor’s motives, they painted an idyllic scene of fishing, cultivation, and food-gathering in a tropical setting. The wholesome food and the pleasant process of obtaining it stand in subtle but pointed contrast to the quality of Paco’s food and the nature of the establishment” (fig. 16).[55] Thus, the mural exemplified the artists pushing back against a patron’s vision. Painted with assistance from Cervantes and Olivo, the mural celebrated an abundance of indigenous healthy foods while implicitly protesting the harm of fast food, whether from Paco’s Tacos or McDonald’s.

At a 1974 reception celebrating the completion of Para el Mercado, local reporter Michael Nolan asked why murals were happening “now and not ten years ago, why is it happening here and not elsewhere?” Muralist Patricia Rodriguez responded:

I think murals are happening all over the country, really, but the murals to me, the murals to us, seem significant, meaning that we no longer feel that art should be kept in the galleries, or in private collections. Everybody should have the same enjoyment of art. . . . Putting it on a wall is more significant for everybody, as well as for ourselves, so that everybody can enjoy it and see what it’s about. And they learn from it, too, everybody who comes by (fig. 17).[56]

Figure 17. Paco’s Tacos Mural in San Francisco’s Mission District – 1974 Dedication, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b_si6rS6RL4. Produced by Michael Nolan and Optic Nerve, uploaded June 7, 2010.

The video captures the public excitement over the completion of the mural and the celebratory spirit of the mural reception. Crowds of people flocked to the opening to celebrate the new mural, dance to the sounds of the live salsa band, and welcome this new art shaping the neighborhood. The video is a rare time capsule to see not just the art but also the experience of welcoming the art to the neighborhood.

Sadly, like many of the murals from this period, Para el Mercado no longer exists. Its easy erasure also points to the limited attention city leaders and esteemed arts institutions granted to murals at the time. Alejandro Murguía poignantly recalled the loss of several of these murals:

The colorful mural by Mujeres Muralistas, Para el mercado, on the corner of Twenty-fourth and South Van Ness, which was painted on a slat fence about eight feet high and some ninety feet long and featured scenes from tropical America, was destroyed several years ago and the wood carted off as scrap. My comadre salvaged a four-foot piece of it, the brown woman with a fishing net, and it now stands among the geraniums in her backyard. The developer who tore it down for an office/apartment building claimed he didn’t know it was important. No one notified the women artists who painted the mural, nor any other community art group; not even the Art Commission knew about this act of vandalism. A half-dozen other murals have been destroyed, including the one by Gilbert Ramírez on the Lulac Building and the murals at the former Army Street (now César Chávez Street) projects that were recently torn down. Even the murals by the comic book artists Spain Rodríguez and R. Crumb, some of the first done in the early 1970s, have gone the way of dust.[57]

While muralists may not have anticipated permanence, Murguía’s words capture some of the disregard that murals have experienced. And, of course, his words communicate how such losses were never just about the art, but also the community’s history incorporated into these images. While the murals are no longer physically present, Proyecto Mission Murals makes reflecting on the art, the artists, and their impact far more possible.

Coming Full Circle at the Mini Park

Our tour starts and ends with the 24th Street Mini Park, which blossomed into one of the most impressive mural sites in the neighborhood. The park opened in 1972, a product of Mayor Joseph Alioto’s 1968 electoral campaign to create accessible recreational spaces out of small vacant lots in densely populated spaces.[58] Inspired by a program in Philadelphia, Alioto’s office proposed to dedicate $650,000 in federal funds to the creation of thirty-three mini parks in areas of the city “with limited playground facilities.”[59] By 1971, sixteen of these parks existed, including two in the Mission—Mayor Alioto Mini Park at 20th and Capp, and one on Shotwell between 15th and 16th Streets.[60] Thus, the 24th Street Mini Park was not the first to exist in the neighborhood, but its proximity to Galería de la Raza, almost across the street, contributed to it becoming a focal point for mural painting.

Starting with Quetzalcoatl, Ríos, Machado, and Montez painted several murals in the mini park shortly after it opened, steadily filling the three surrounding walls with dramatic images crafted from Indigenous histories and contemporary concerns. Given the relative expansiveness of the space, the male artists unexpectedly shared the opportunity with Las Mujeres Muralistas. As Rodriguez recalled, “Michael Ríos went to the City to propose a mural project there in order to improve the park and make it usable again. He was given the money, and he invited us to paint there as well. We were surprised but also knew we finally had been accepted as muralists by the male artists.”[61]

In 1975, Las Mujeres Muralistas created Fantasy World for Children, a colorful mural full of fantastical animals and plants to spur the imagination of children in the park (fig. 18). For Patricia Rodriguez, this invitation to paint in the mini park represented a new era of respect and inclusion. The park emerged as a middle ground, not exactly indicative of men and women working together, as their murals remained in separate spheres, but with a step toward inclusion and recognition.

The gendered geographies that emerged in this period illustrate various forms of inclusion and exclusion that shaped the muralist community at this time. But these separate spaces also proved inspirational. Diverse art flourished on the walls of the neighborhood, giving visibility to imaginative possibilities, Indigenous histories, and powerful calls for social justice.

In 1985 Ralph Maradiaga passed away unexpectedly at age fifty. Yañez recalled, “When Ralph passed, there was a vacuum in our hearts and the Chicano community.”[62] As a way to recognize Maradiaga’s work in the community, especially his support of the muralists, the park was renamed in his honor. Tirso Araiza painted a mural of remembrance, El Juego de la Resistencia, in 1988. With a touch of magical realism, Araiza incorporated a yellow school bus with a human head, a city Muni bus with an upside-down passenger, and a figure riding a bicycle in the shape of a fish. The quirky assemblage of real and impossible figures represented the mural’s title (The Game of Resistance) and perhaps paid homage to Maradiaga’s efforts for the community. Unfortunately, and tellingly, the city neglected care of the Ralph Maradiaga Mini Park for several years and the mural had to be removed “due to a lack of maintenance.”[63]

However, a 2006 beautification project amplified the work of the original muralists.[64] With advocacy from Susan Cervantes and Precita Eyes, artist-couple Colette Crutcher and Mark Roller created a sculptural Quetzalcoatl covered in mosaic, undulating through the playground. Maradiaga would have loved this playful visual poetry created in a space in his honor. In 2015, Araiza returned to the park to repaint El Juego de la Resistencia (fig. 19), which now oversees this glorious snake. Araiza shared a fitting quote for remembering Maradiaga and the many muralists who reimagined what the Mission District could be: “It is only through artistic, social and political ideologies that we ascertain and retain a place in history and document it for our children.”[65]

Notes

- Alex Hidalgo, Trail of Footprints: A History of Indigenous Maps from Viceregal Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2019), 11.

- Galería de la Raza curated, raised funds, and coordinated neighborhood mural arts in diverse ways, including appropriating an advertising billboard fixed to its building to serve as a temporary mural space. The gallery created a time-lapse video to present the diversity of featured murals across decades of creativity: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJHJu4_LJv4. For Proyecto Mission Murals, Ella Diaz analyzed the gallery’s provocative 1982 In Progress exhibition, which commissioned twenty artists to create temporary murals alongside each other inside the gallery. https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts-recovering-a-conceptual-mission-mural/

- Ralph Maradiaga created several screenprints that adapted Aztec imagery, including images of an Aztec War Shield, an Olmec head, and Tezcatlipoca, for a series of calendars produced by Galería de la Raza in the early seventies. He also drew Mayan imagery for an animated sequence in a film he cocreated as Rafael Maradiaga with Julio Rossetti called A Measure of Time (1975). He also curated many exhibits and directed the film El Pueblo Chicano: The Beginnings (1979), dedicated to the early histories of the Americas.

- For an expansive overview, see Alan Barnett, Community Murals: The People’s Art (Philadelphia: The Art Alliance, 1984); Eva Cockcroft, John Weber, and James Cockcroft, Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1977). Timothy W. Drescher offers an important overview of murals in the Bay Area in San Francisco Murals: Community Creates Its Muse, 1914–1994 (Hong Kong: Pogo Press, 1994).

- A newspaper reproduction of the mural in late August 1974 helps establish that this mural was completed in the summer of 1974. Margot Patterson Doss, “The Mural-Bright Mission Today,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, Sunday Punch, August 25, 1974.

- Walter Blum described the rise of the city’s mini parks in “Ever See a Mini-Park?” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, November 21, 1971.

- “In the Mission, the bright-hued shades of Rivera,” San Francisco Examiner, November 7, 1976.

- Provincializing stereotypes often hamper seeing the transnational cosmopolitanism of barrios (Latino neighborhoods). See Gina M. Pérez, Frank A. Guridy, and Adrian Burgos Jr., Beyond El Barrio: Everyday Life in Latina/o America (New York: New York University Press, 2010).

- El Tecolote reprinted sketches from Graciela Carrillo’s travels in “Ecos de la Misión,” El Tecolote, August 3, 1973; Alexandria Regilio, “Michael Ríos: From square world to hip one,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 27, 2010; Dianne Demoss Campusano, interview with the author, July 10, 2018; Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez, interview with the author, February 5, 2003; Irene Pérez, oral history, conducted by Camilo Garzón for SFMOMA, July 12, 2021, [15:17:25].

- Rodriguez recalls first meeting Yañez, Carrillo, Ríos, Méndez, Pérez, Concha, and others at the San Francisco Art Institute. Patricia Rodriguez, “Mujeres Muralistas,” Ten Years that Shook the City: San Francisco 1968–1978, ed. Chris Carlsson (San Francisco: City Lights Foundation Books, 2011), 81–91.

- Katy Butler, “The Performing Arts Center: Subsidy for the Rich,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, February 14–27, 1974. Cary Cordova, The Heart of the Mission: Latino Art and Politics in San Francisco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 70.

- “Art for Harold’s Sake: How Big Business Regulates the Arts in San Francisco,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, November 21–28, 1975.

- See Cordova, Heart of the Mission, 70–71.

- Ceci Brunazzi, “Writing on the Walls: Murals in the Mission,” Common Sense, May 1975.

- Patrick Rosenkranz, ed., My Life & Times: Spain, vol. 3 (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2020), 11.

- Jerome Tarshis points out that Crumb received no pay in “The Reluctant Celebrity,” San Francisco Examiner, California Living magazine, February 27, 1972, 26; Matthew L. Schuerman, Newcomers: Gentrification and Its Discontents (University of Chicago Press, 2019), 74.

- “Youths Get Paid to Learn How to Beat Poverty,” San Francisco Examiner, October 31, 1966; “Federal Aid for Mission Dropouts,” San Francisco Examiner, March 1, 1968.

- “Keep on Chunkin’” evolved from Crumb’s unintentional popularizing of another phrase, “Keep on Truckin,’” which he had used as the title of one of his early comics. The comic featured men with very large feet moving to lyrics inspired from an old blues song. In an interview, Crumb explained how he had learned the phrase “Keep on Truckin’” from the blues, both as a reference to a particular dance and as innuendo for sex. See Al Davoren’s interview of Crumb in R. Crumb: Conversations, ed. D. K. Holm (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 72–76. The earlier phrase became so commercialized that Crumb sought ways to undermine the shallow marketing, including using “Keep on Chunkin’,” which was purposefully obtuse. For more on Crumb’s use of “Keep on Truckin’” and his fight to copyright the phrase, see The Handbook of Comics and Graphic Narratives, ed. Sebastian Domsch, Dan Hassler-Forest, and Dirk Vanderbeke (Boston: De Gruyter, 2021), 489–92.

- Rosenkranz, My Life & Times, 3:11. An article on Crumb helps pinpoint the completion of the Mission Rebels mural as early 1972. Tarshis, “Reluctant Celebrity.” Sources suggest the Horizons Unlimited mural was completed in late 1971 or early 1972. Barnett offers 1971 in Community Murals, 126; Drescher lists 1972 in San Francisco Murals, 19.

- Regilio, “Michael Ríos.”

- Tomás F. Summers Sandoval Jr., Latinos at the Golden Gate: Creating Community and Identity in San Francisco (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 120.

- Carmen Castro, “Mission Muralists: Art Statements of the Mission,” El Tecolote, July 26, 1972.

- Michael Ríos, oral history, conducted by Camilo Garzón for SFMOMA, [00:13:07].

- Castro, “Mission Muralists.”

- Ríos described presenting his sketch to “some people of MCO and Legal Aid and they approved it,” in Castro, “Mission Muralists.” Two other sources reference the building as housing legal aid: Barnett, Community Murals, 14; Eva Sperling Cockcroft and Holly Barnet-Sánchez, Signs from the Heart: California Chicano Murals (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993), 36.

- Richard Phinney, “San Francisco’s ‘secret’ gallery,” Vancouver Sun, June 4, 1983.

- Carlos Vidal Greth, “Murals of the Mission,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 24, 1988.

- Cordova, Heart of the Mission, 126–51.

- Cordova, 83.

- Patricia Rodriguez, interview with author, March 27, 2003.

- Rodriguez, March 27, 2003.

- Rodriguez.

- Barnett, Community Murals, 128–30.

- Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez, oral history conducted by Camilo Garzón for SFMOMA, June 6, 2021, [00:36:00].

- On San Francisco’s slow steps toward desegregation, see David Kirp, Just Schools: The Idea of Racial Equality in American Education (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 84, 108, 111. In my study of Children’s Book Press and its work with muralists, I discuss artist–activist interventions to the limited school curriculums of the sixties and seventies. Cary Cordova, “Portable Murals: Children’s Book Press and the Circulation of Latino Art,” Visual Resources: An International Journal of Images and Their Uses 33, nos. 3–4 (September–December 2017). Gary Orfield discusses how critical the 1964 Civil Rights Act was in spurring desegregation, but he also points out how “There never was any significant attempt to desegregate Latino children, except in a handful of districts. As their numbers grew, their segregation steadily increased. The Supreme Court did not recognize the right of Latino children to desegregate schools until 1973.” See Orfield’s “The 1964 Civil Rights Act and American Education,” in Legacies of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, ed. Bernard Grofman (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 117.

- See Kenneth J. Meier and Joseph Stewart Jr., The Politics of Hispanic Education: Un Paso Pa’lante y Dos Pa’tras (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 79–80.

- Galaviz, oral history, June 6, 2021, [00:40:02].

- Also see Cordova, Heart of the Mission, 144–45.

- Barnett, Community Murals, 133.

- Rodriguez, “Mujeres Muralistas,” 87.

- Rodriguez, 81.

- Rodriguez and Drescher describe this mural as painted in 1972. Rodriguez, “Mujeres Muralistas,” 81; Drescher, San Francisco Murals, 22. Brunazzi pinpoints 1972 as the year Balmy Alley murals first emerged. Brunazzi, “Murals in the Mission,” 8. Barnett and Shifra Goldman dated the mural’s creation to 1973, placing the mural later than the male artists working on the murals at Horizons Unlimited, Mission Rebels, and the MCO. Barnett, Community Murals, 134; Shifra Goldman, “How, Why, Where, and When it All Happened: Chicano Murals of California,” in Signs from the Heart, 23-53 (40); Shifra Goldman, Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 213. This troublesome dating encourages seeing women artists as followers, rather than as parallel creators. Rodriguez and Galaviz affirm that women were working on Balmy Alley murals in 1972 in written and oral accounts.

- Rodriguez, “Mujeres Muralistas,” 81.

- Irene Pérez, oral history, SFMOMA, [15:26:05].

- Pérez, oral history, SFMOMA, [15:10:42].

- Pérez, [15:14:26].

- Pérez, [15:18:09].

- Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, “Ancient Stone Sculptures: In Search of the Mexica Past,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, ed. Deborah L. Nichols and Enrique Rodríguez Alegría (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 21–28.

- Moctezuma, “Ancient Stone Sculptures,” 21.

- William Barnes, “Aztec Art, Time, and Cosmovisión,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, ed. Deborah L. Nichols and Enrique Rodríguez-Alegría (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 585–93, quotation on 590.

- Pérez, [15:17:25].

- Consuelo Méndez speaking at the Frente Conference, February 8, 1975, video recording, Freedom Archives, accessed June 13, 2022, https://search.freedomarchives.org/search.php?view_collection=1048&title=Frente+Conference+-+San+Francisco+1975+%28video+clip%29.

- Cordova, Heart of the Mission, 135–36.

- The Culinary Workers Union fought McDonald’s restaurants opening in San Francisco as anti-union. While Bonilla did not run a union restaurant, he saw the potential damage a McDonald’s next door could do to his business, local traffic, and as an unsupervised youth hangout. The muralists did not grapple with the implicit labor issues in their expression of support. “Hot Hamburger Beef Served Up to City,” San Francisco Examiner, July 25, 1973; Denise Holley, “Mission Sí, McDonald’s No,” El Tecolote, February 22, 1974; “McDonald’s Appealed,” El Tecolote, June 10, 1974; “Burger Chain Sues Longtime City Foes,” San Francisco Examiner, October 3, 1974; “‘Big Mac’ angry,” El Tecolote, November 22, 1974.

- Brunazzi, “Murals in the Mission,” 15.

- “Paco’s Tacos Mural in San Francisco’s Mission District – 1974 dedication,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b_si6rS6RL4.

- Alejandro Murguía, The Medicine of Memory: A Mexica Clan in California (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 193.

- In a campaign advertisement, Alioto promised to “create mini-parks and protected tot lots out of littered, vacant lots thoughout our city, from the Mission to the Sunset.” San Francisco Examiner, November 3, 1967. See also Blum, “Ever See a Mini-Park?”

- Blum wrote, “The idea came from Philadelphia, where an extensive mini-park system flourishes,” “Ever See a Mini-Park?” 38. Statistics from “Alioto Dedicates 3 Mini-Parks,” San Francisco Examiner, June 14, 1969.

- Blum, “Ever See a Mini-Park?”

- Ríos may have been inspired by muralist Raymond Howell’s proposal to “renovate the mini-park over the N-Judah tunnel” as referenced by Kathie Wagner and Lori LuJan in “Public Works: San Francisco,” part 1, Sunday Examiner and Chronicle California Living, September 21, 1975, 26.

- Laura Wenus, “Baile en la Calle Offers Art, Dance and Solidarity,” Mission Local, May 4, 2015, https://missionlocal.org/2015/05/baile-en-la-calle-offers-art-dance-solidarity.

- Wenus, “Baile en la Calle.”

- Zahid Sardar, “Garden Snake: A Piece of the Bigger Picture,” SF Gate, December 16, 2006, https://www.sfgate.com/homeandgarden/article/Garden-Snake-A-piece-of-the-bigger-picture-In-2482168.php.

- Wenus, “Baile en la Calle.”