Little did I know, when our Architecture + Design curators asked me to activate SFMOMA’s iPhone 1, what a rabbit hole I was about to dive into! The occasion was the exhibition Typeface to Interface, where the phone would be on view alongside other objects representing important moments in the history of communications technology. Unlike in past presentations, where it would have been displayed as a beautifully designed object—as we might show an iconic Olivetti typewriter or Alessi teapot—for this exhibition we wanted to give visitors an idea of its capabilities and what the user experience was like.

This idea reflects a recent change in our thinking about design exhibitions and the museum’s role in preserving design. Yes, the objects are masterfully made and in that way alone can tell a story. But beyond their outer shells lies a colorful world of user interface and software design that is just as much a part of the device and its history. But how to make this hidden world accessible to visitors in the galleries? How to display experience?

Awakening from its “100-year-sleep”

Before we could figure out the “how,” we first needed to find out what this experience was. We needed to wake up the phone from its mint-condition “100-year-sleep.”

Any object in our collection is regarded as precious and unique on the order of a Matisse painting, and is treated with that level of caution. When handling works of art, we don’t consider whether or not to wear gloves—we know to protect them from fingerprints. With the iPhone 1, however, we wondered if the swiping function would even work with gloves on. (It does.) And further questions: Could we take pictures with it, or would that compromise its “original” condition? Could we “leave traces” by saving numbers into the contacts? In a nutshell: How far could we loosen our usual guidelines, given that this was, in the end, a mass-produced utilitarian object?

Even the seemingly straightforward procedure of turning the phone on turned out to be quite challenging. Ironically it was the museum’s previous preservation approach that was now responsible for a big problem: the iPhone couldn’t be activated because it had never been turned on before.

To explain: Back in 2007 when it was acquired, we didn’t have plans to ever display more than the object itself. Thus there was no incentive to think about the preservation of the software interface. And maybe we thought that if we eventually changed our minds, we could always turn it on. Without knowing, we left the iPhone to its own, irreversible fate. Alas, iPhones don’t come with preinstalled software. When I turned our collection phone on, it immediately asked to be connected to a computer so that it could download the latest operating system. In 2016 that would be iOS 9, which was historically inaccurate for our phone (and wouldn’t even run on it, anyway). And iOS version 1.0—its original operating system—could no longer be downloaded from the Apple Store.

Tune in, turn on

After check-ins with the AT&T store and Apple tech support, my case ended up on the desk of a senior advisor, who said our only option was to find a backup of the software version we wanted and restart the phone via iTunes to that backup version. In other words, we needed to find another iPhone 1 with an old iOS installed and boot from there.

This looked like the ideal solution to many of the issues outlined above, since we could also then freely handle this second phone. Original iPhones are widely available on eBay for a couple hundred dollars, so we purchased one to experiment with. It came with historically appropriate iOS 3.1.3 software, which was the latest upgrade for this generation of iPhones.

We spent a whole day at our offsite research facility, the Collections Center, with curators, technicians, registrars, and conservators, experimenting with the iPhone 1, the Macintosh 128k, the Palm Pilot, and Google Glass—all of which you can see in the Typeface to Interface exhibition. Playing with different display options, we considered how best to convey their functionality to visitors: Should we make them fully accessible to the public? Display them turned on? Or show videos of people using them? In the end, our curators went for that last option.

Getting at the core

At SFMOMA we have a long history of collecting media art, and very early on we implemented conservation efforts into our programming. Whenever we acquire a new work, install it in the galleries, or send it out on loan, we get in contact with the artist and/or their representatives to discuss the piece. By revisiting our records repeatedly, we effectively distill core elements of the work that we then focus our preservation efforts around.

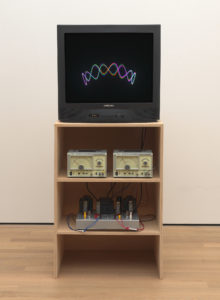

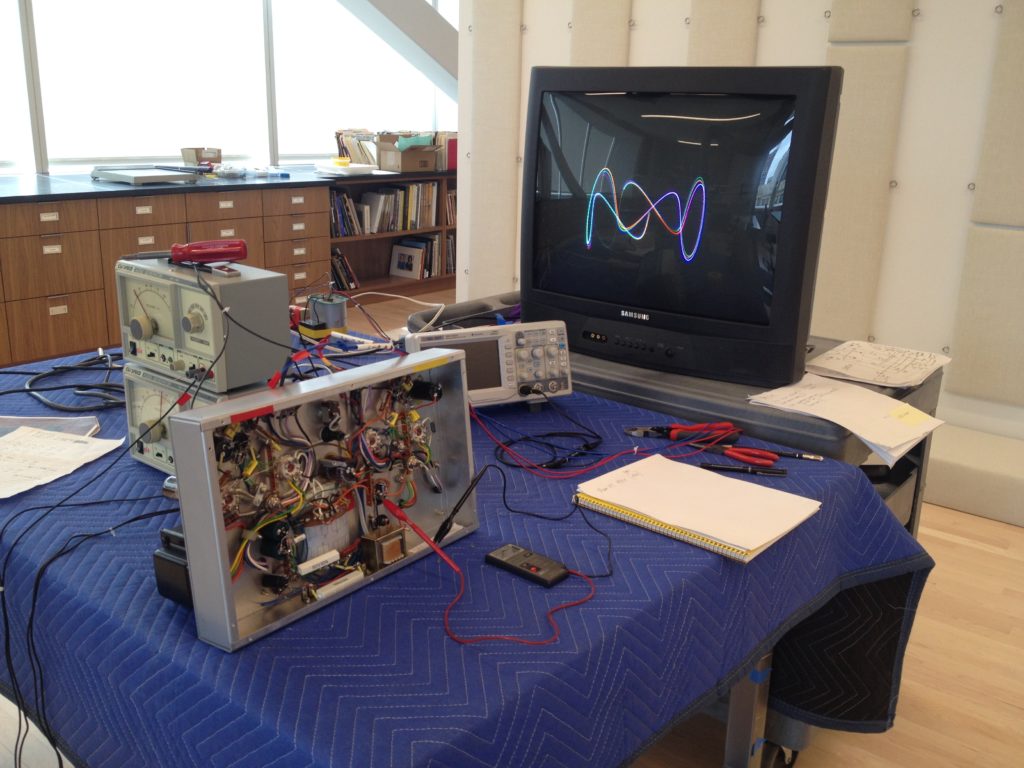

For instance, we ask which components are replaceable, what we can migrate in the future, and what we need to keep in mind when going through migrations. While for some works it may be perfectly fine to move from CRT monitors to flatscreens, other works, like Nam June Paik’s TV Crown (1965/1999) or Zen for TV (1963/1990) (both currently installed in the fourth-floor Campaign for Art exhibition) include monitors that were manipulated by the artist in such a way that they became inherent parts of the work—functionally, sculpturally, and conceptually—and cannot be easily replaced with similar-looking monitors.

The custom built amplifier in Nam June Paik's TV Crown, 1965/1999

In dealing with shifts in technology and artworks that are so prone to obsolescence—be they software-based design objects like the iPhone 1 or complex video installations—we’ve learned that, unlike with delicate paintings or works on paper, the healthiest thing we can do with our media arts collection is to put it on view and send it out on loan. Because it is in these moments of installation and transition when the work crystallizes. In storage, it is is only a group of inactive components: a videotape and a monitor, or a hard drive and a computer. It needs to be activated within a platform, be it a videotape player, a digital media player, or an operating system, to reveal its content.

Rapid obsolescence

Platforms of playback likewise become outdated and no longer available. (Try to play even a DVD nowadays. Maybe you still have a DVD player or a computer with a DVD drive, but it’s for sure much harder to find one than it was a couple of years ago!)

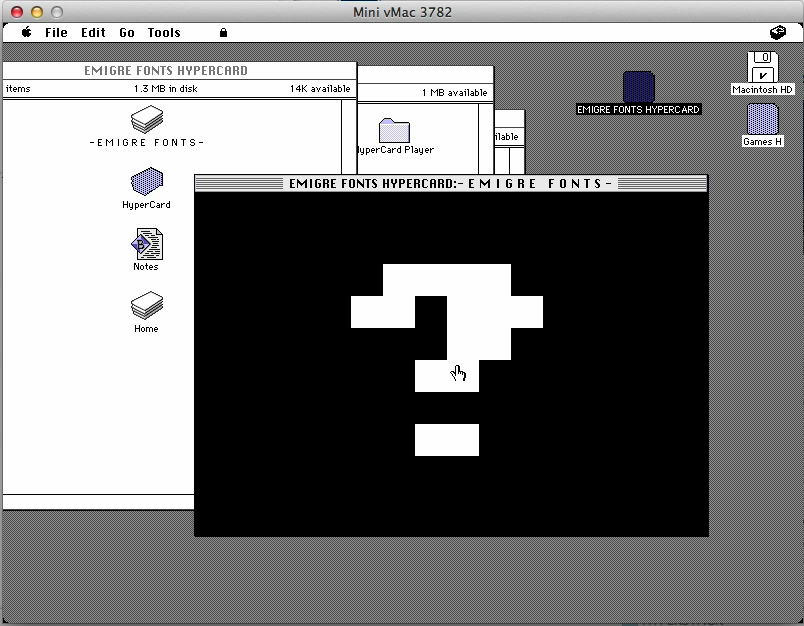

Take for instance the work Emigre Fonts HyperCard stack (1990) by the design studio Emigre, which is on view in Typeface to Interface. It entered our collection on a floppy disk. While it is shown as a video in the exhibition, it is actually a program—a file created with software similar to PowerPoint called HyperStack that ran on early Macintosh systems. Our file has one interactive component: when you start it, the first slide displays a large question mark. Once you click it, the program, which is more like a complex slide show, starts running. In order to make the work come to life we had to get at it from three angles: First we had to extract the contents from the floppy disk by using a KryoFlux, a USB-based forensic floppy controller. Then we had to get our hands on a copy of the HyperCard software, which came out in 1987 and was discontinued in 2004. And lastly, we needed to create an environment in which the software could run. (The specific term for that is emulation.)

The Emigre Hyperstack program inside the Mini vMac OS9 emulator

With the help of software technology consultant Mark Hellar, we got Mac OS 9 (introduced in 1999) to run virtually on one of our contemporary computers. There was some work involved in customizing the emulator and defining its memory (RAM), since the original file didn’t have any sort of speed control programmed into it and was running as fast as its hosting computer was able to. With a modern-day computer, that was of course way too fast! If you check out the work in the exhibition, you can see that it is hard to determine the correct replay speed just from looking at the content, since the designers play with acceleration in the piece.

As with the iPhone 1, we thought a video could convey the experience really well. So for the exhibition, we created a screen capture of the running program.

Another work in the show that can be experienced in its original interactive form is John Maeda’s Flying Letters (1996). In the exhibition you see it as a screen capture of our curator of Architecture + Design, Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, interacting with the work. But we also built an in-browser emulator to run the program online, which lets you experience it in its original Mac OS 9 environment at home on your computer! Thanks to video gamers, there is a large community out there with a great interest in keeping these obsolete operating systems alive, and we are lucky to be able to tap into this incredible resource for the viewing and preservation of media artworks.

Full disclosure: the iPhone 1 you see in the Typeface to Interface video is the one we got from eBay. The video is displayed right next to our collection phone. The phone from eBay turned out to be jailbroken, thwarting our plans to do the iTunes backup maneuver. We’ll keep looking. In the meantime, our collection phone remains the inactive design object it was acquired as—and, maybe, a mute cautionary tale of the risks for loss in the quickly evolving world of technology design. So, if you’re this close to dropping a fortune on a sealed “vintage” iPhone, beware: you might just end up with a very beautifully designed shell.