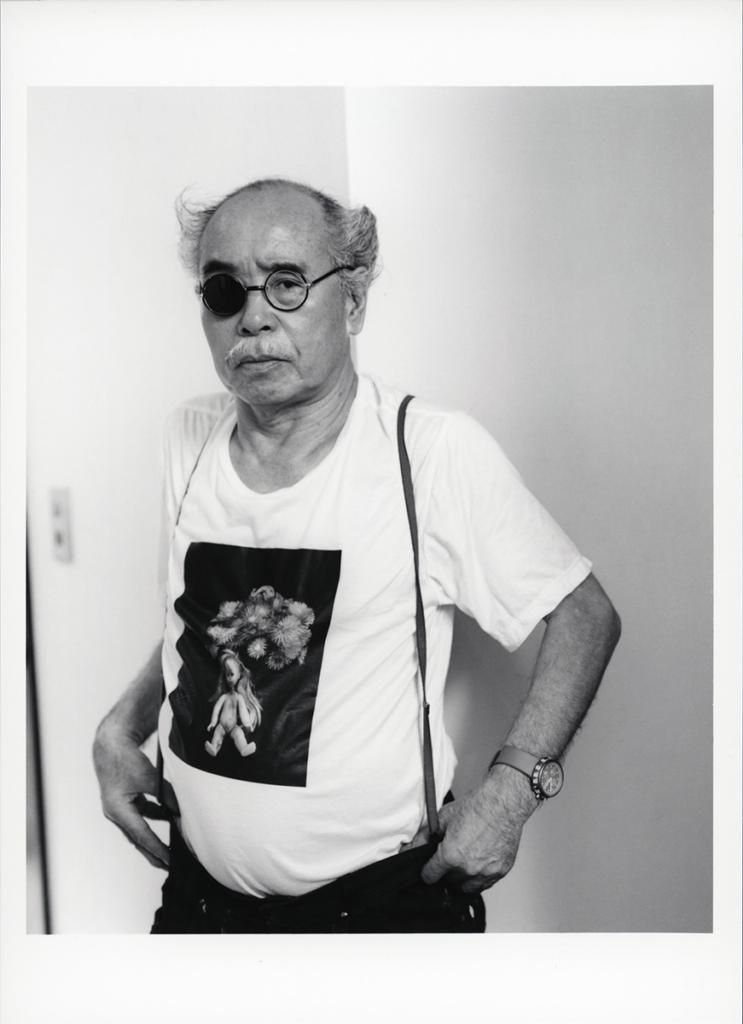

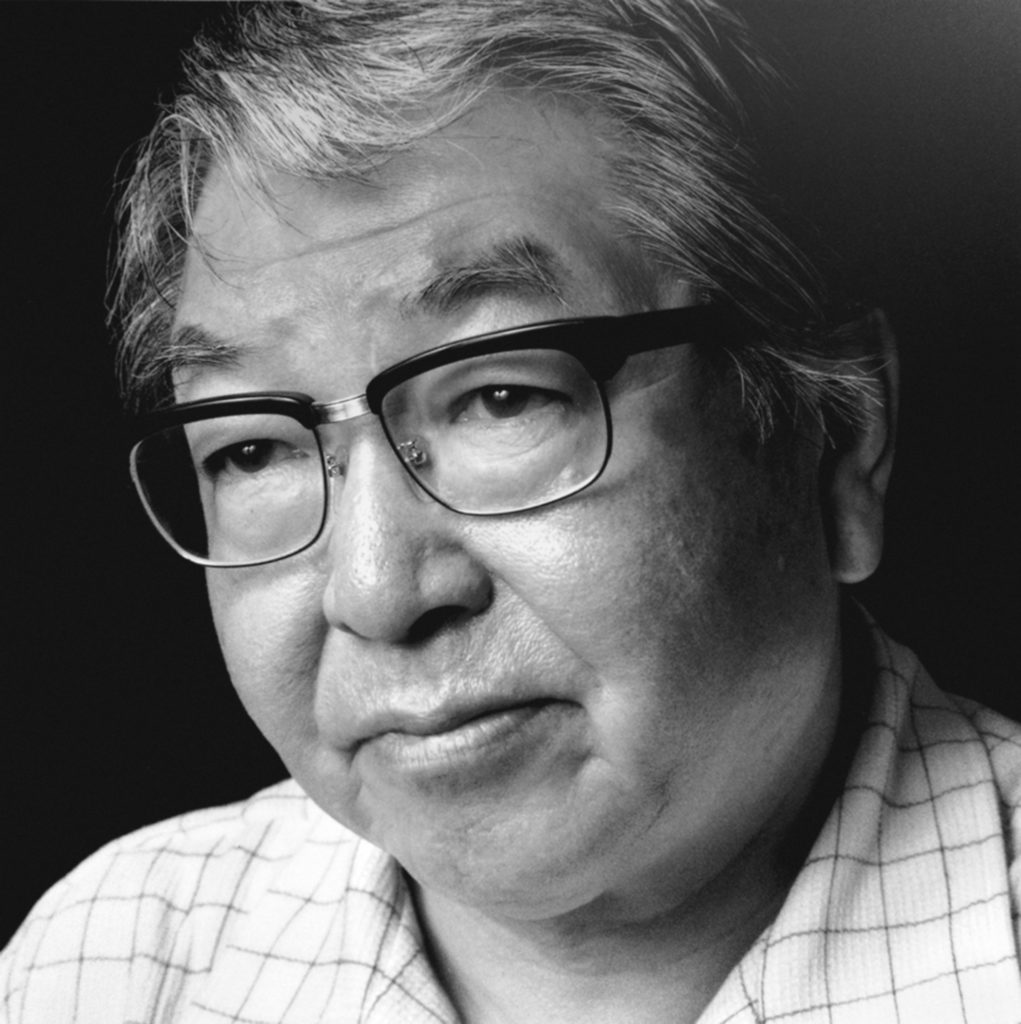

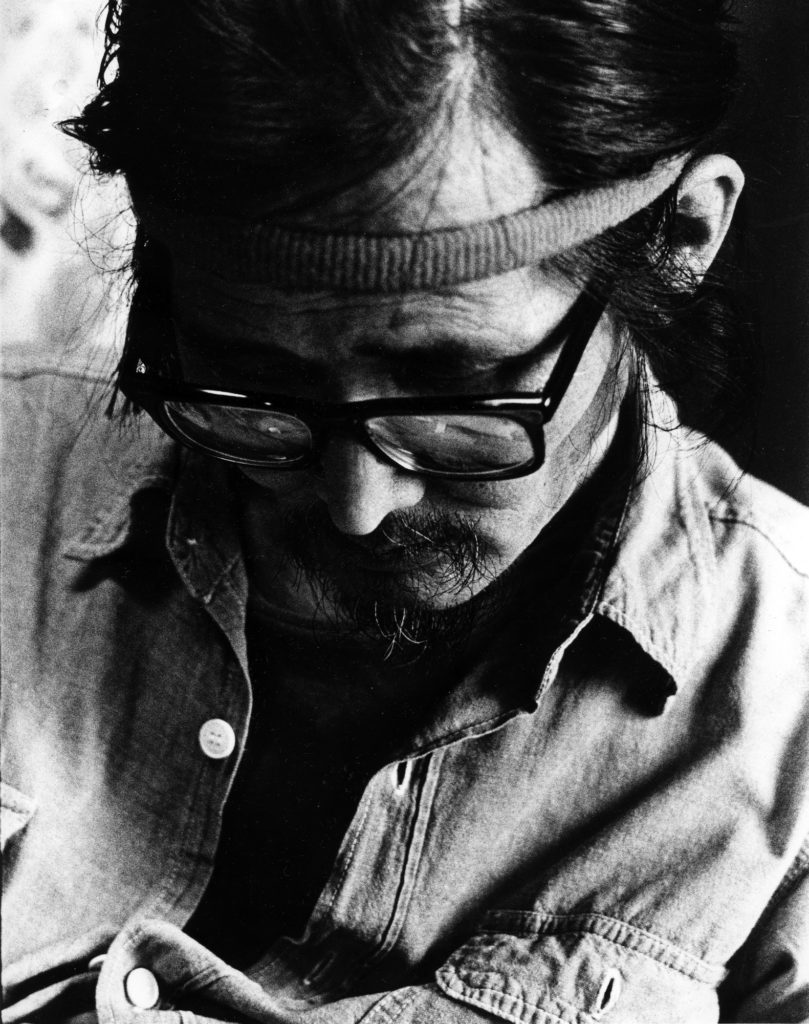

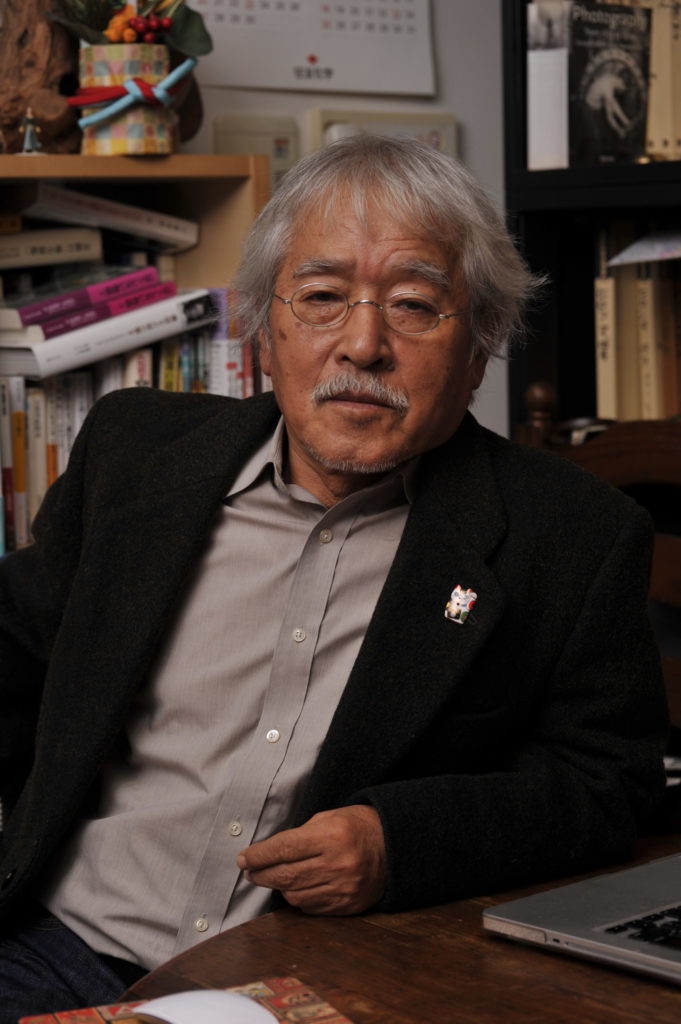

Artist

Naoya Hatakeyama

Japanese

1958, Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture

Naoya Hatakeyama (b. 1958) examines the meaning of landscape in the present day, when all land is affected by human activity. He maintains that even landscapes we admire for their untouched beauty, such as the craggy mountaintops of the Alps, have been altered by human use—by their portrayal as idealized Nature—and we must recognize this as the current condition of the world. Thus his work embodies an acceptance of human participation in nature.[1]

Hatakeyama was born in northern Japan and studied art at the University of Tsukuba. He admired the countryside and the natural beauty of the mountains in his home region. In 1983 , when he had his first exhibition in Tokyo, at Zeit-Foto Salon, he showed a group of black-and-white pictures of the traces humans had made in that still relatively open land: a modest lighthouse, plowed fields, shadows cast on a newly paved road. He moved to Tokyo the following year, and this brought the relationship of the countryside to the city into active dialogue in his work. He also began working in color, a practice he continues today.

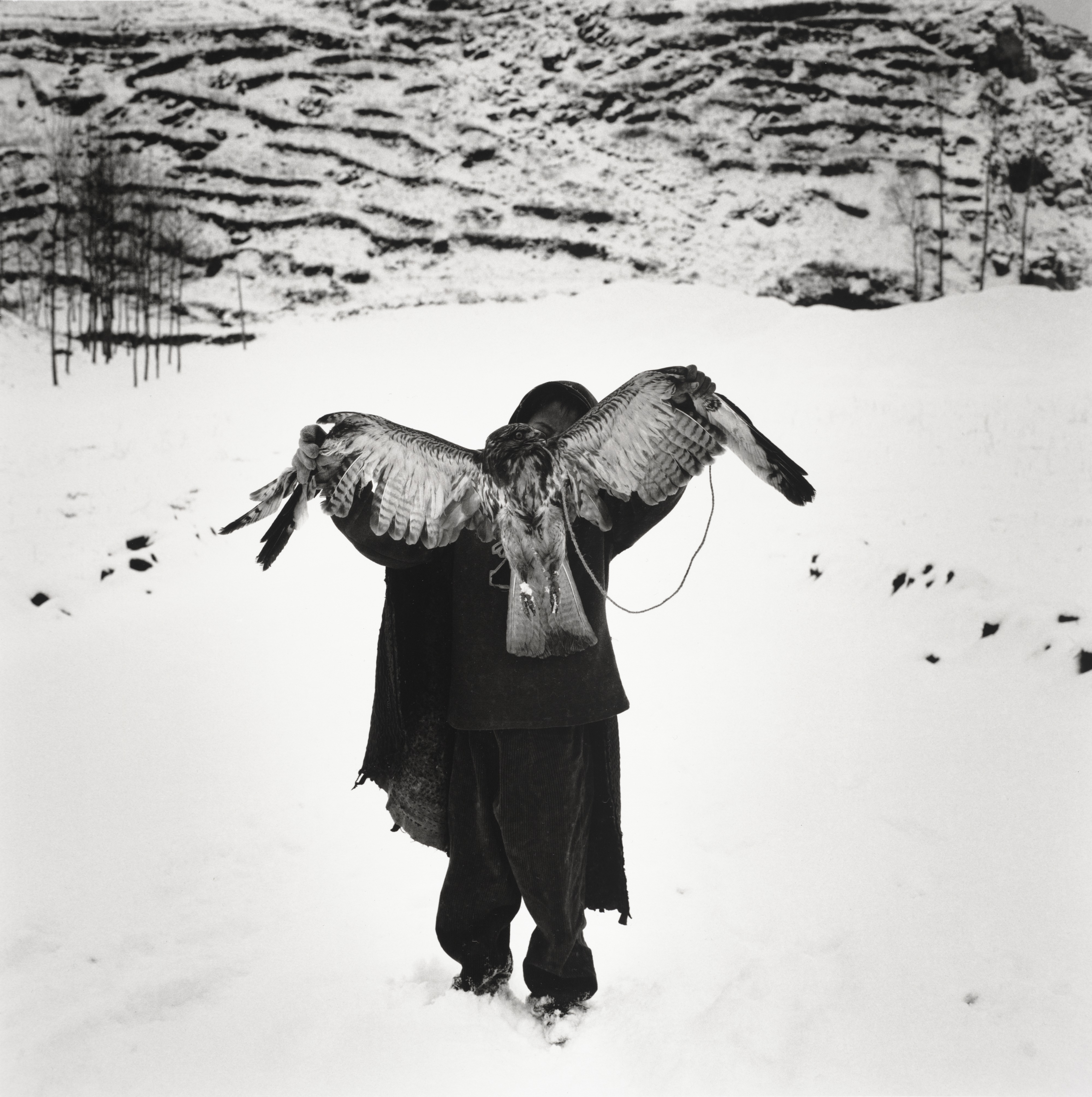

Hatakeyama’s first major project was Lime Hills (1986–90), in which he photographed limestone quarries throughout Japan. Finding the peaceful contemplation of these places to be incomplete, he soon documented the detonations the engineers devised to loosen the rock and represented the choreographed explosions sequentially, in the series Blast (1995–2008). “When I learned that Japan was a land of limestone,” Hatakeyama has said, “my appreciation of its cityscapes underwent a subtle change.” The country’s abundant supply of the stone is used to make cement and as aggregate for concrete, among other things. “In the texture of concrete I can feel the trace of corals and fusulinas that inhabited warm equatorial seas 200 to 400 million years ago.”[2] Flying over Tokyo, he was reminded of the quarries: “The uneven white scene spreading endlessly was not the limestone I had seen in the mine, but the buildings of the city of Tokyo. It suddenly appeared to me that the minerals in the huge emptiness had not simply disappeared but were carried all the way here to be transformed and exist right in front of me.”[3]

In his series Untitled (1989–2005), Hatakeyama photographed the city from distant vantage points. The resulting pictures, shown either individually or arranged in a grid, look like geological sections. This initiated an intense focus on Japan’s urban structures. The River series (1993–94) pairs Tokyo’s built structures with the often luminous and mysterious waters on which the buildings are constructed. In Underground (1998–99), he followed the city’s sewers below its surface, carrying in lights to see what was hidden there. He also made pictures of buildings at night, presenting them backlit, in light boxes, so that the structures appear to emit their own magical illumination (Maquettes/Light, 1995–97). Untitled, Osaka (1998–99) comprises side-by-side views of a temporary model-home show and its subsequent demolition. Hatakeyama finds a particular beauty in these urban subjects, which he presents objectively and without judgment.

He has also examined the dialogue between nature and culture in Europe in both the past and the present. His series Ciel Tombé (2006–8) depicts tunnels in northern Paris, created over centuries by the quarrying of stone for construction of the city and now destabilized and decaying; in a related photograph (1991, printed 2011) the same area is seen from above. He has photographed the dismantling of mining operations in Northern Europe, including areas now designated UNESCO World Heritage sites to memorialize the industry that once sustained local communities, in the series Zeche Westfalen I/II Ahlen (2003–4). Other pictures by Hatakeyama show the apparently natural beauty of slag heaps, like perfectly shaped mountains (Terrils, 2009–10).

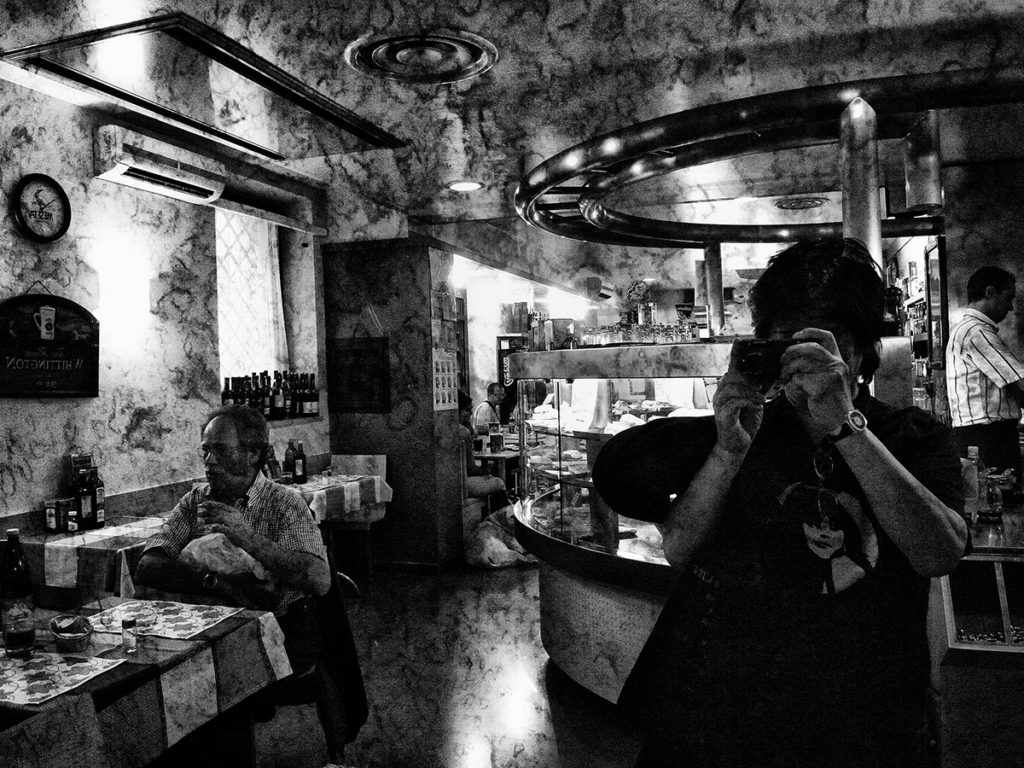

Hatakeyama’s focus was altered by the devastating 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, a tragic moment for the nation and personally for the photographer, whose hometown was almost completely demolished and who suffered terrible loss. Since then he has studied not only the devastation caused by the disaster, but also the experience of returning to the affected region many times in the years since and witnessing the radical changes taking place. It has provoked him to rethink his work, particularly the separation of his own private or personal photography from his work as an artist. His Rikuzentakata series (2011) brings together personal photographs made in the past with pictures of the stages of reconstruction.[4] Finally, Hatakeyama has examined the stance of observation itself. CAMERA (1995–2009) is a series of photographs made in hotel rooms at night, accumulated during Hatakeyama’s travels over several years. They show what the photographer sees from his hotel bed, lit by reading lamps; they describe only the lighted interiors (camera is Italian for room). Comprising a meditation on the very nature of photography, these pictures emphasize the internal, cognitive, and analytic nature of the medium, detached even as it is involved in examining the world outside.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

- See the artist’s talk presented at the Izu Photo Museum, Nagaizumi, Japan, January 2013.

- Naoya Hatakeyama, Lime Works (Tokyo: Synergy Kikagaku, 1996), 54. See the artist’s talk presented at PhotoAlliance, San Francisco, September 2006.

- Naoya Hatakeyama quoted in Stephan Berg, “Down to the Water Line,” in Naoya Hatakeyama, ed. Stephan Berg (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2002), 12.

- See the artist’s talk presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, April 2015.