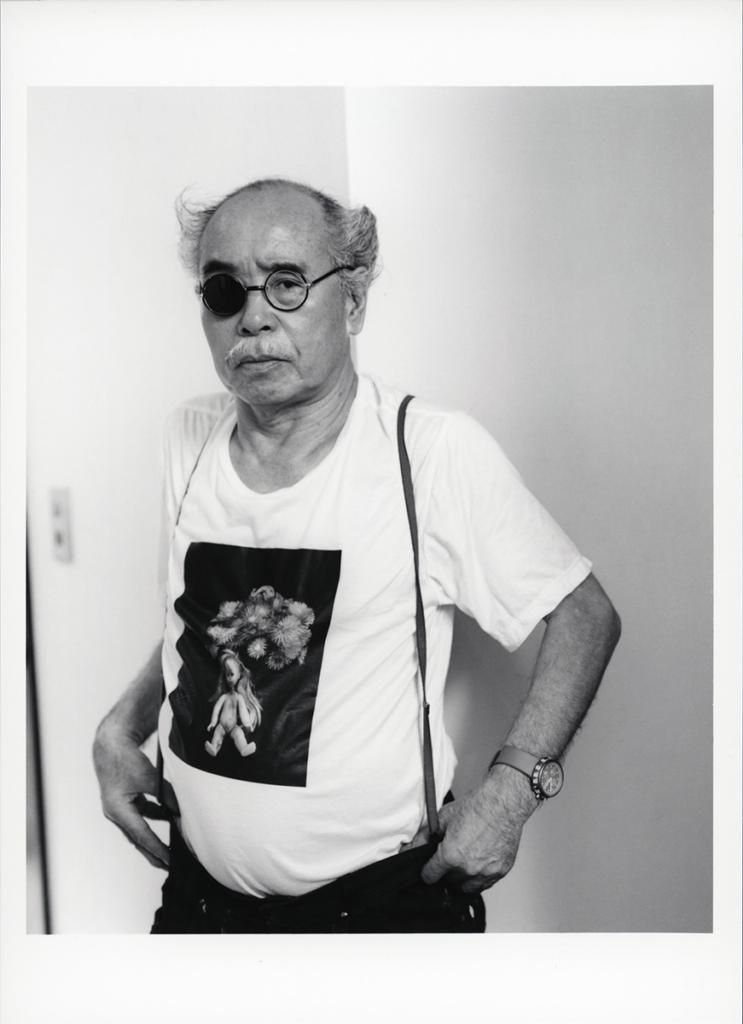

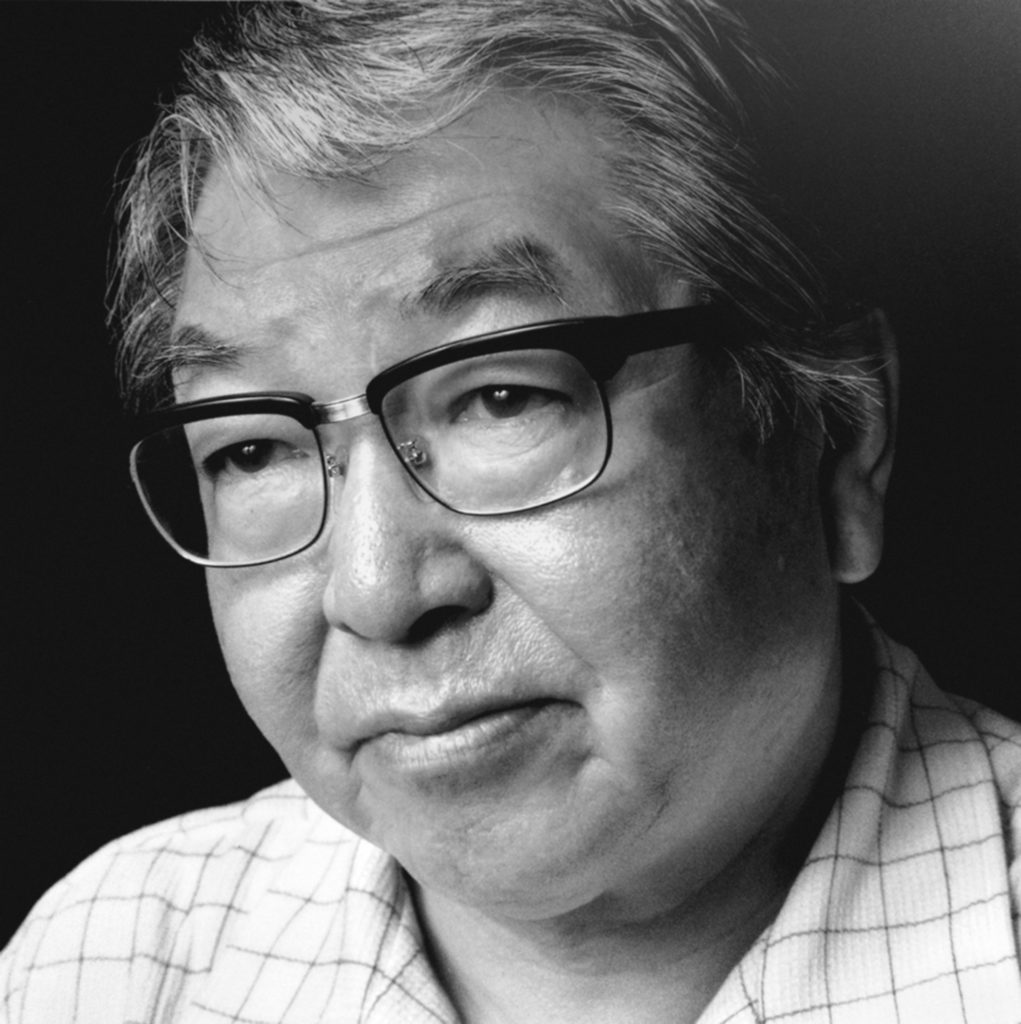

Artist

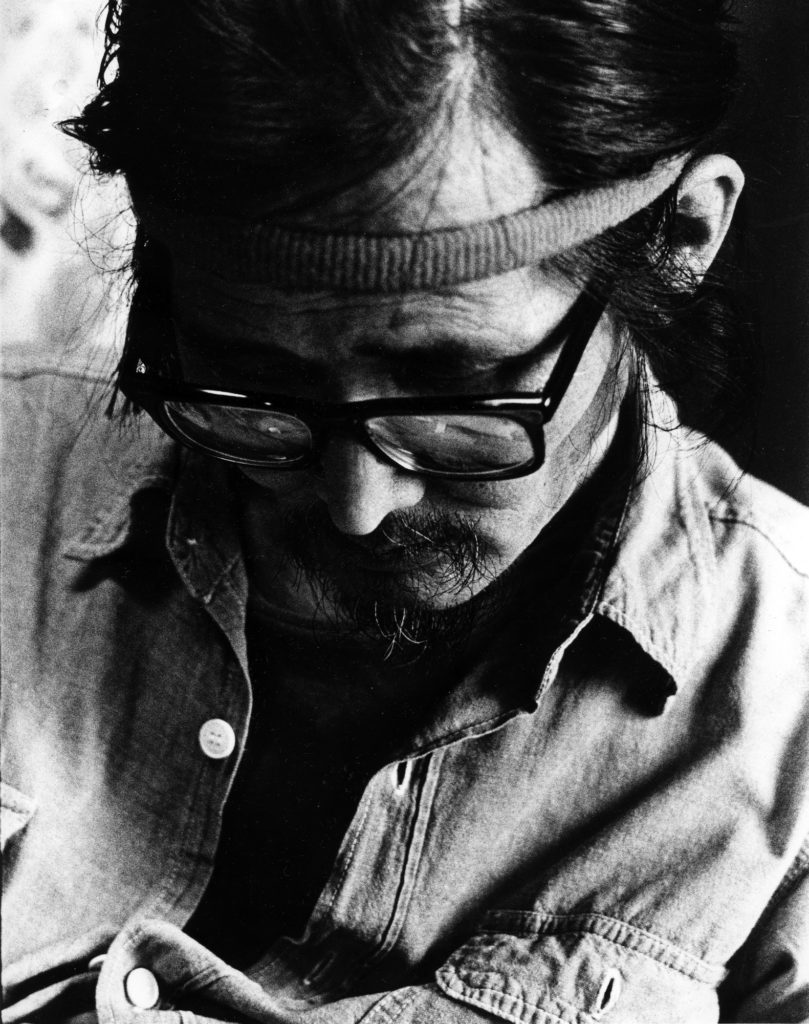

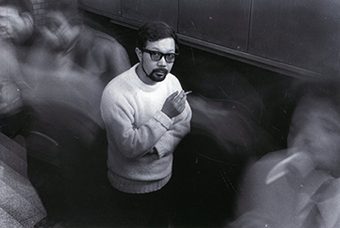

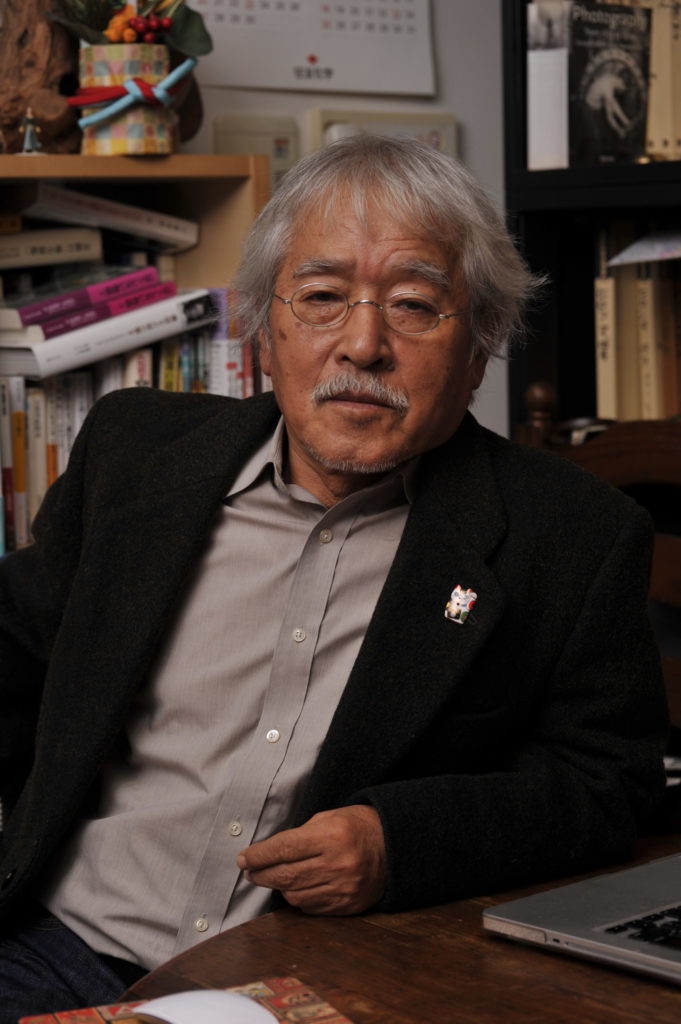

Hiromi Tsuchida

Japanese

1939, Minamiechizen, Fukui Prefecture

The opening sequence of Zokushin: Gods of the Earth (1976), a photobook by Hiromi Tsuchida (b. 1939), shows a group of people picnicking in the woods above a rice paddy. As the already drunken farmers grow progressively more intoxicated, they roll around on the ground, joke with one another, and gesture at the photographer. The pictures are black and white, and in this sense, they belong to an established tradition of documentary photography in Japan. However, the playful streak that runs not just through this series, but through Tsuchida’s entire career, sets his work apart from that of his predecessors.

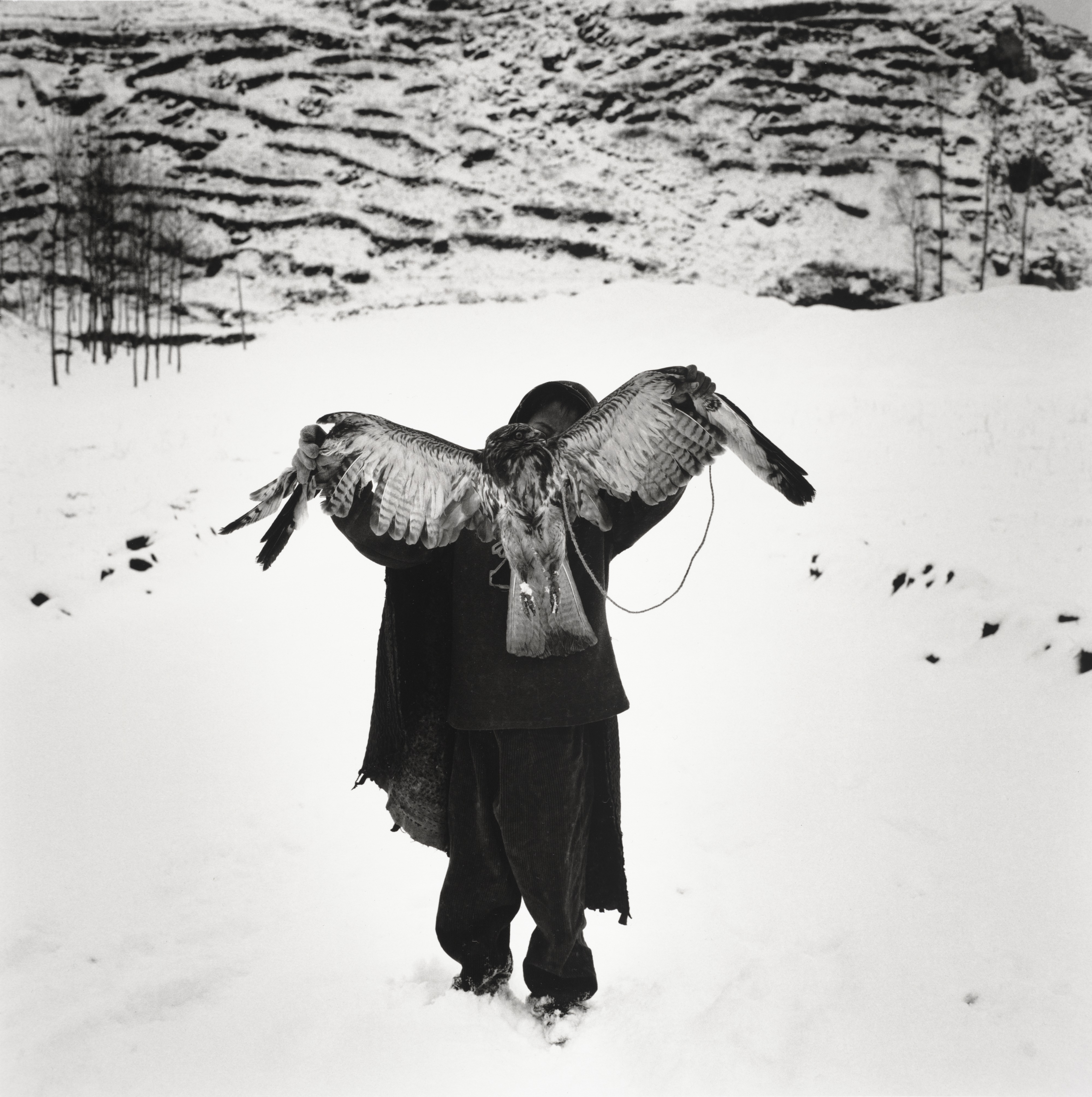

After working as a commercial photographer, from 1964 through 1966 Tsuchida studied at the Tokyo College of Photography in Hiyoshi, Yokohama, where he learned a conceptual approach to the medium from the noted critic Koen Shigemori. Zokushin was his first major series, published across several issues of the magazine Camera Mainichi before the pictures were collected in a book. The project was the result of his travels through Japan in the early to mid-1970s, as he sought out ways of life not yet homogenized by the capital flowing from urban centers. While some of the photographs were taken in Tokyo’s Asakusa district—“pleasure quarters” in days gone by—the bulk of them were made in more remote areas. Several pictures show the encroachment of the tourism industry, one of various factors that would eventually flatten the distinction between “urban” and “rural.” The object of Tsuchida’s attention, however, was not so much the scenery as it was the local cultures and people. Two of his photographs in Aomori Prefecture, for example, show a group of women in traditional dress and a singer in the midst of a performance. The images focus on the figures’ clothing and expressions; the singer’s face, in particular, projects controlled yet intense emotion.

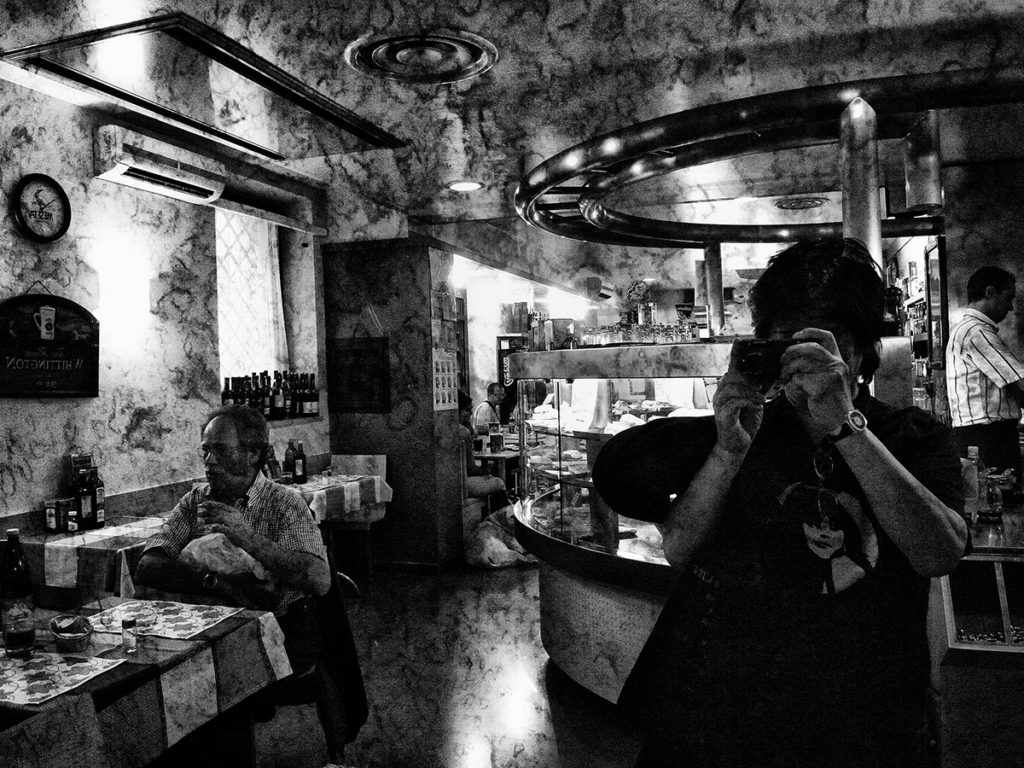

Whereas in Zokushin Tsuchida dealt with people in rural areas soon to be swallowed up by urban ways of life, in his next major series, Counting Grains of Sand (1990), he trained his gaze firmly on the inhabitants of major cities. The book starts with snapshots of a few scattered individuals, but eventually more and more figures fill the frame, culminating in images of the crowd that gathered in front of the Imperial Palace after the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989. Thousands of men and women are packed into each of the final photographs, revealing the wry meaning of the title: people are no more than grains of sand, infinitesimal parts of a vast collective. Tsuchida has also depicted cities with a view to history—he has made photographs in Hiroshima and Berlin since 1973 and 1983, respectively, often returning to the exact same spots to make new exposures years later.

Tsuchida extended Counting Grains of Sand in color in the 1990s and beyond, capturing crowds at popular tourist destinations throughout Japan. In these later works he used new technology in a somewhat cheeky way, inserting himself digitally into all of the pictures. This gives them an almost zany, Where’s Waldo? quality, and it seems to show that Tsuchida considers himself no better than, or different from, those he records on film. He has also experimented with digital techniques in other bodies of work—in 1988 he started photographing himself nearly every day, long before such projects became viral sensations, and in 2008 he made a time-lapse video from the images. In these ways Tsuchida continues to bring a sense of humor and playfulness to his examination of social phenomena.

— Daniel Abbe