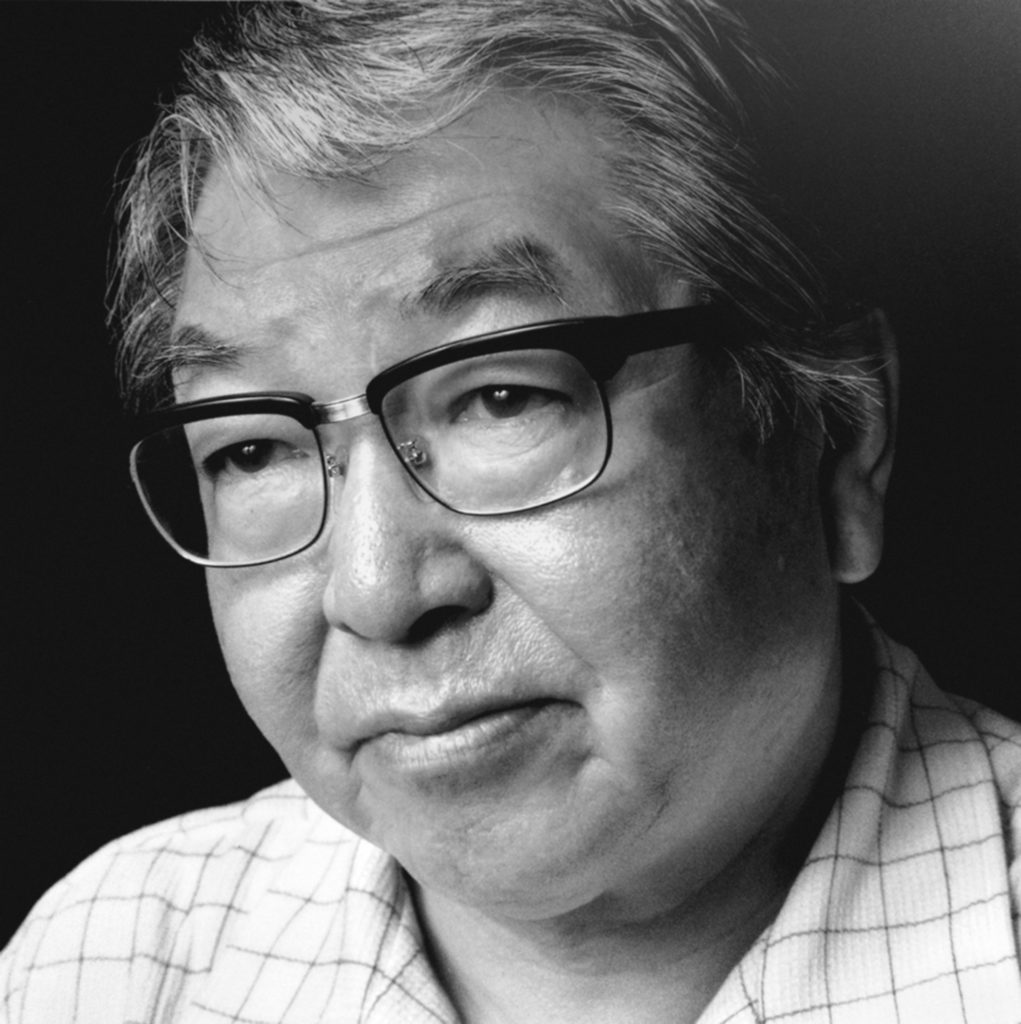

Artist

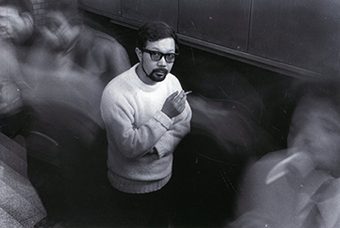

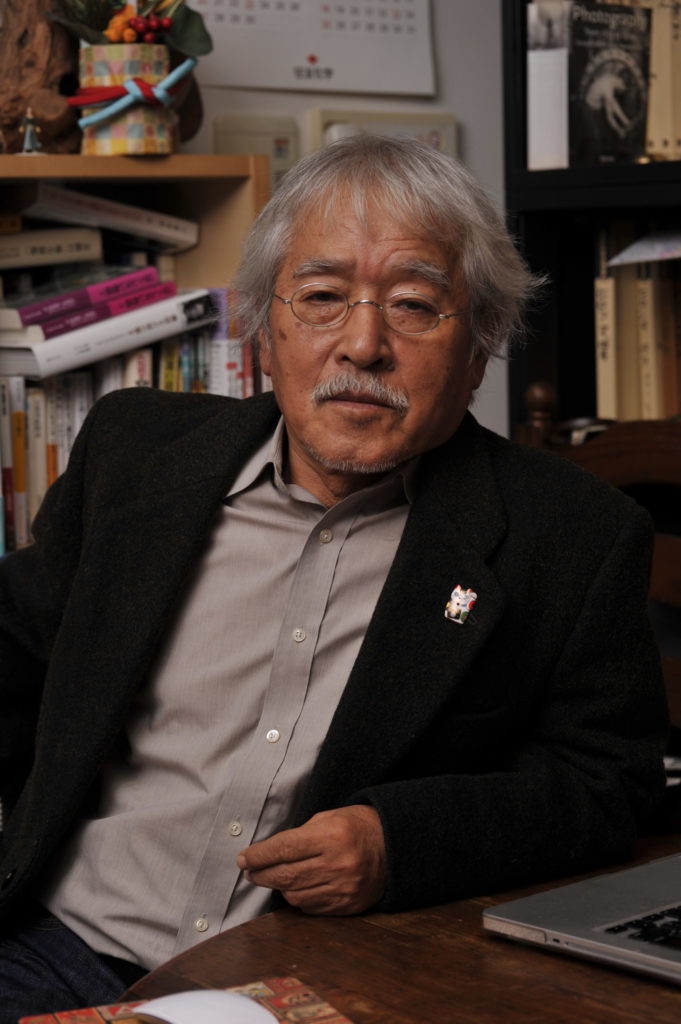

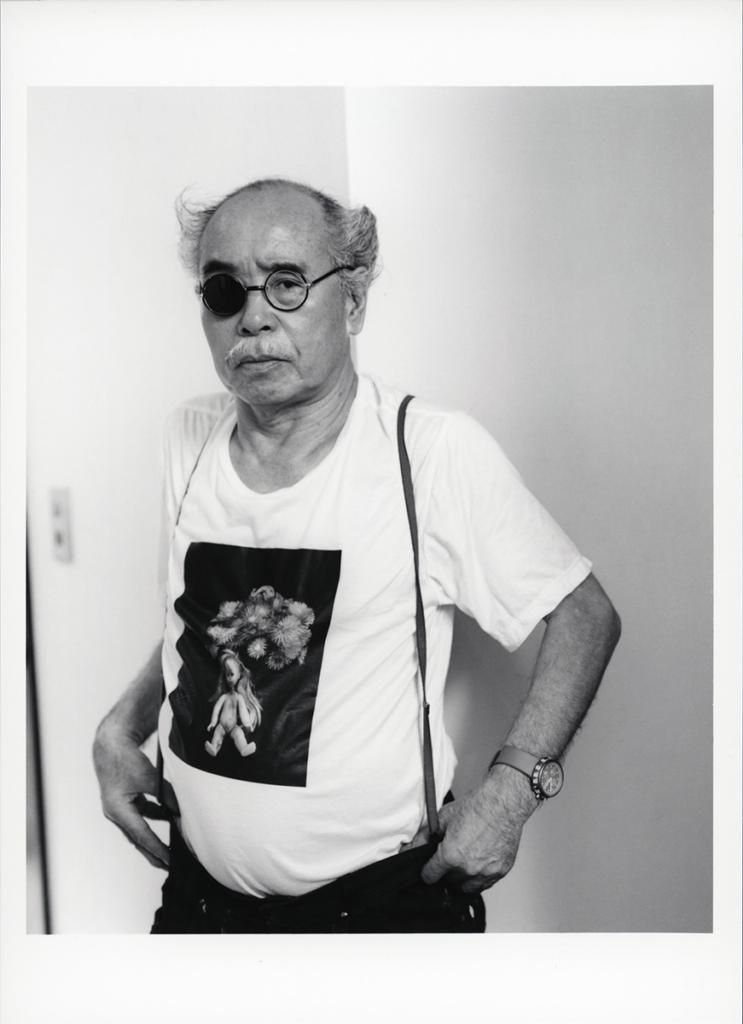

Nobuyoshi Araki

Japanese

1940, Tokyo, Tokyo prefecture

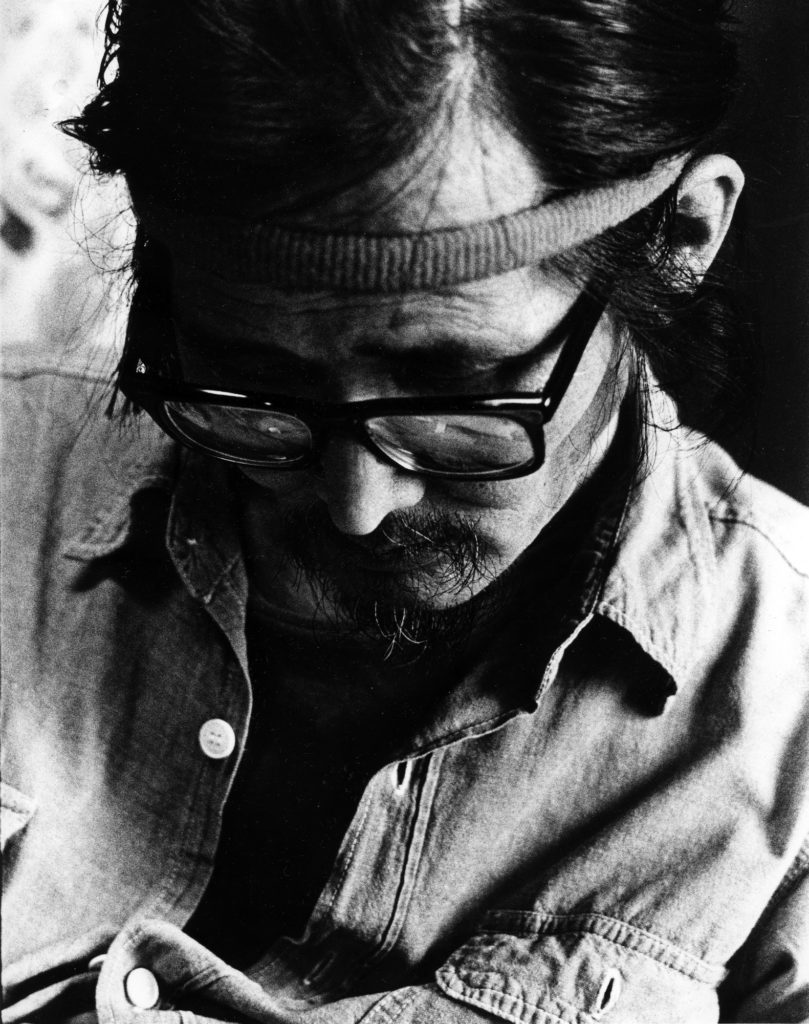

One of the most prolific figures in the field of Japanese photography, Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940) has produced countless pictures and more than five hundred photobooks since 1970. Such an abundant body of work defies easy categorization, an endeavor made all the more challenging by Araki’s experimentation with media including collage, film, and, more recently, Polaroid instant technology. Araki’s wry, irreverent work, frequently employing sexual subject matter, has often ignited controversy and earned him a degree of notoriety. The frenetic nature of his photographs, which he tends to shoot with very little preparation, is emblematic of the Japanese experience of World War II and its chaotic aftermath.

Araki entered Chiba University in 1959, majoring in photography and film. The regimented and technical nature of the program, then situated in the engineering department, was unappealing to the nonconforming Araki. The film he turned in as his final project, however—Children in Apartment Blocks (1963)—served as the germ for one of his earliest photographic series, for which he received an award from Taiyo magazine the following year. Satchin (1964) focuses on schoolchildren in the Shitamachi neighborhood of Tokyo, which remained largely unchanged amid the flurry of rapid urban transformation leading up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. After graduation, Araki took a job as a commercial photographer for the advertising firm Dentsu. While he found the work frustratingly dull, he made good use of Dentsu’s well-stocked facilities to pursue photography on his own time, going so far as to illicitly use the company’s photocopier to produce an early photobook.

Two events pivotal to Araki’s life and work took place in the late 1960s: his father died in 1967, and he met his future wife, Yoko Aoki, then working as a typist at Dentsu, the following year. Death and love would become two of the principal driving forces behind Araki’s profoundly human photography, and Yoko would become Araki’s most frequent photographic subject. The couple wed in 1971 and embarked on a honeymoon, which Araki extensively photographed. With its narrative style, personal tone, and vernacular aesthetic, the resulting volume—Sentimental Journey (1971)—is regarded as one of the most important Japanese photobooks of the twentieth century. Araki’s growing success as a photographer allowed him to leave Dentsu to focus solely on his artistic career in 1972.

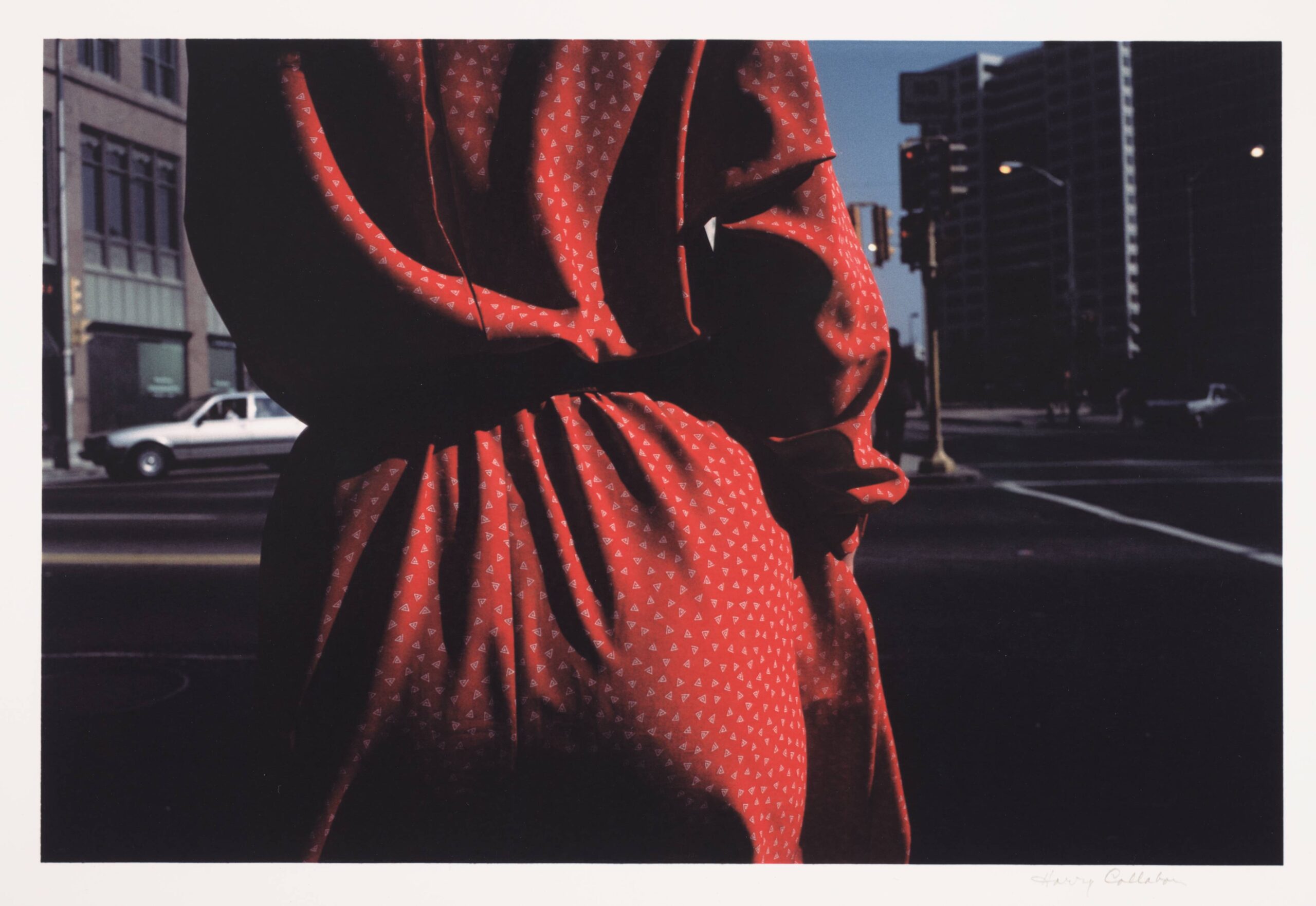

Araki has referred to his wide-ranging and eclectic work as “I-photography,” after the “I-novel,” a Japanese confessional literary genre often written in the first person. His unwavering concentration on his own life and experiences—sexual and otherwise—pushed against the dominant documentary photographic aesthetic, epitomized by such figures as Hiroshi Hamaya, as well as the are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) aesthetic of the Provoke movement, prevalent in Japanese avant-garde photography beginning in the late 1960s. Araki tackled these approaches head-on in his series Pseudo-Reportage. The related photobook, published in 1980, pairs these quasi-documentary pictures with misleading captions, underscoring the problematic nature of photographic veracity.

After Yoko passed away, in 1990, Araki began a host of new projects, even using his own diagnosis with prostate cancer in 2008 as a jumping-off point to explore the diminishing status of analog photography. 2THESKY, my Ender (2009) consists of photographs covered with salt, which will cause the object to deteriorate over time, mirroring the physical decline of the photographer himself. While he was not included in the landmark exhibition New Japanese Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974, organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, he was included in Yamagishi’s second exhibition collaboration in the United States, Japan: A Self-Portrait at the International Center of Photography in New York in 1979. Araki gained international exposure in Europe prior to this, participating in Neue Fotografie aus Japan at the Kulturhaus der Stadt, Graz, Austria, his first group show outside Japan, in 1977. His first international solo show took place in 1992: Akt-Tokyo: Nobuyoshi Araki 1971–1991 at the Forum Stadtpark, Graz.

— Matthew Kluk