Artist

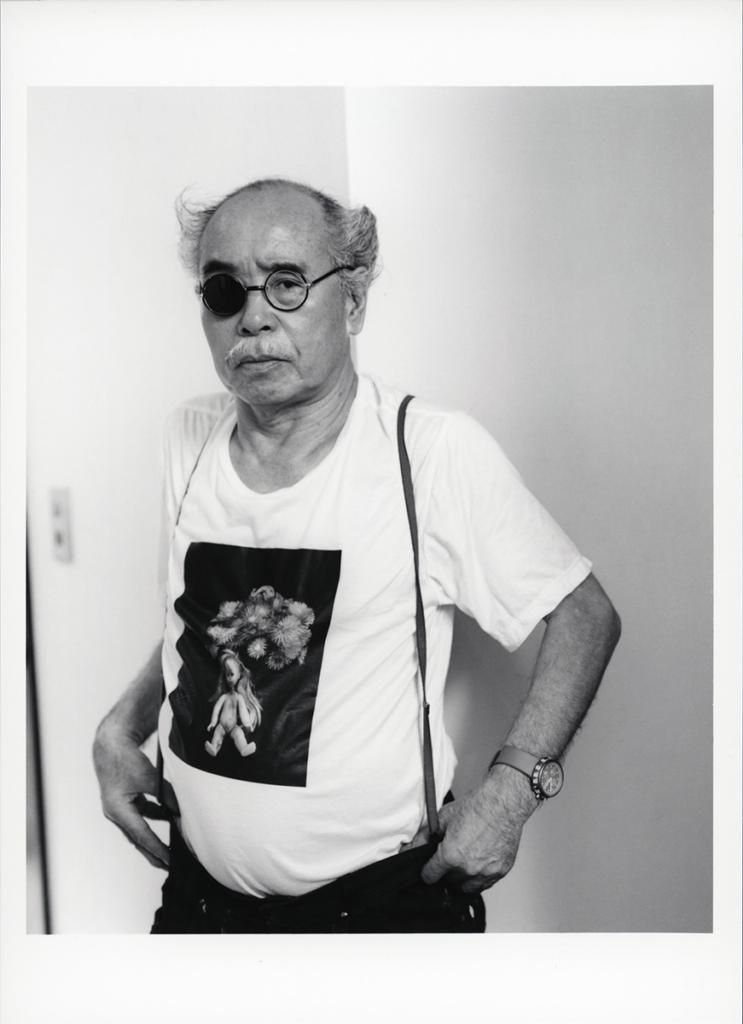

Keizo Kitajima

Japanese

1954, Suzaka, Nagano Prefecture

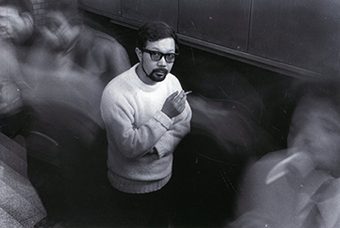

While the photography magazine Provoke ran only three issues, between 1968 and 1969, it had a significant impact on subsequent generations of photographers. Keizo Kitajima (b. 1954) was one of the first and most prominent artists to incorporate its are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) style and its ideals of subjectivity and anti-commercialism into his work.

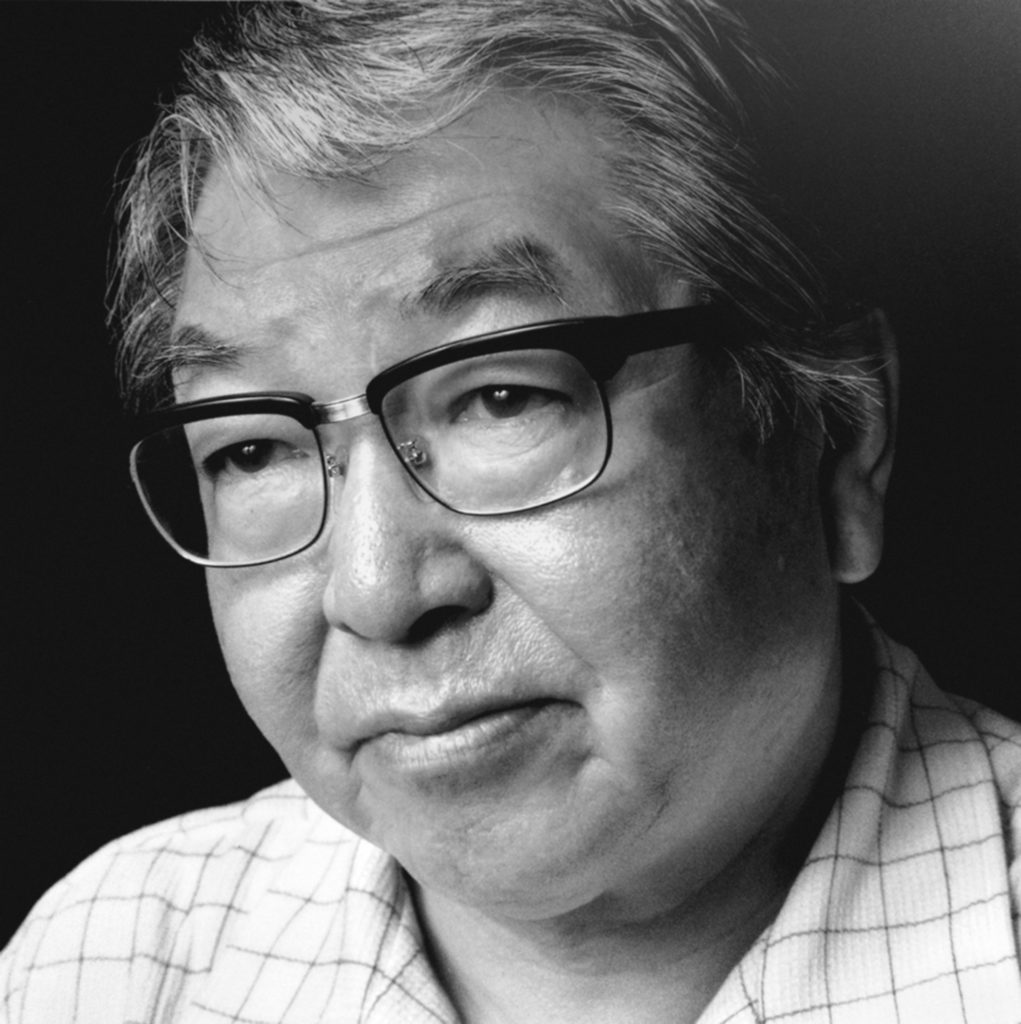

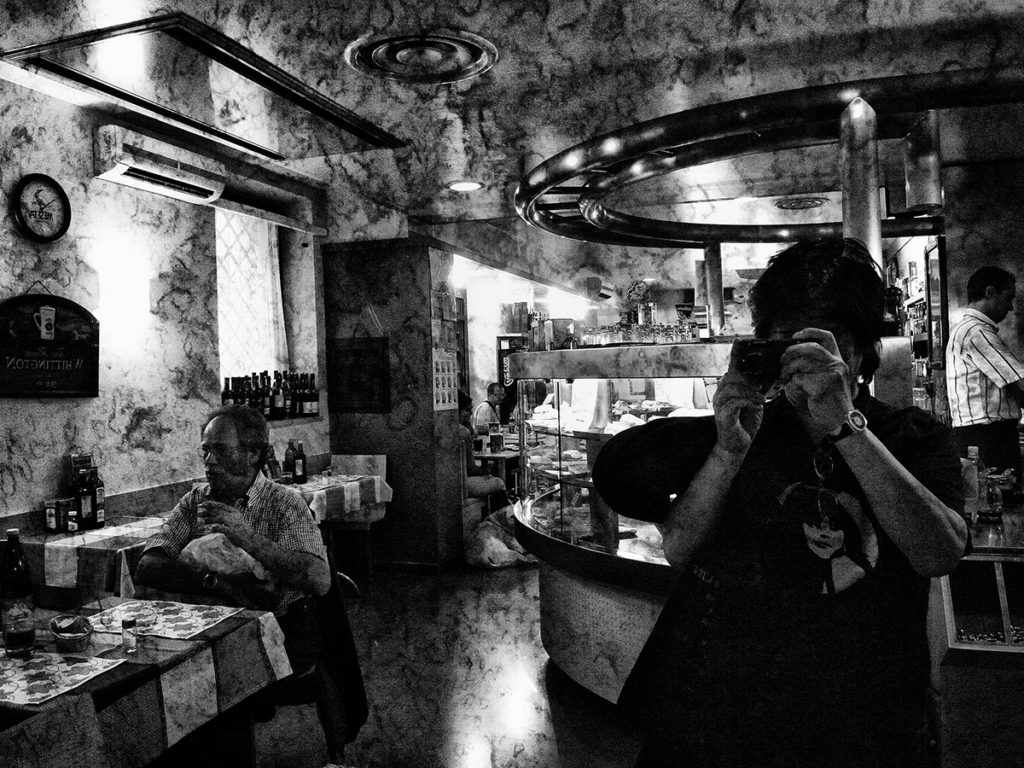

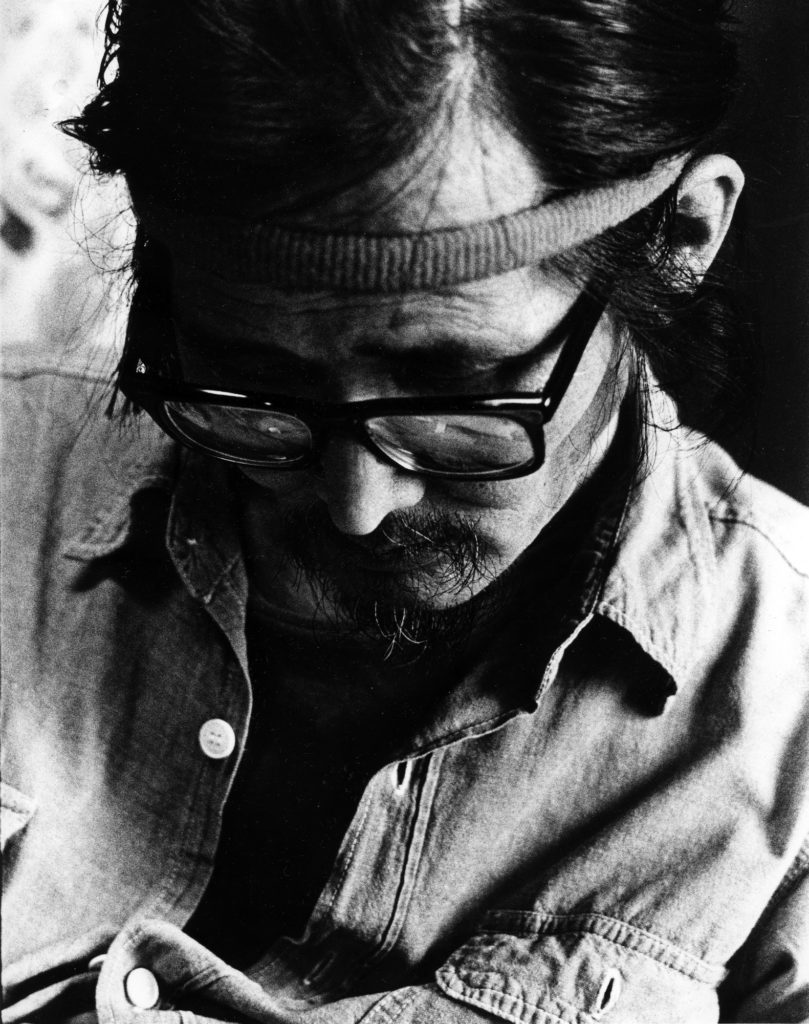

In 1975 Kitajima took a class taught by Daido Moriyama at Workshop Photo School, a photography school founded by several members of the Provoke circle after the magazine ceased production. The class proved foundational, and Moriyama became a lifelong mentor. Just one year later the pair established Image Shop Camp in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo—one of a number of artist-run galleries popping up at the time that served simultaneously as exhibition spaces, darkrooms, and meeting places for like-minded photographers. From January through December 1979 Kitajima presented a monthly series of exhibitions of experimental photographs that he took around Tokyo, accompanied by booklets titled Photo Express: Tokyo. These pictures adopt the are-bure-boke aesthetic of Provoke, but the way the artist figured Japan’s booming consumer culture was distinctly his own: pulling in close to his subjects, he foregrounded their jubilant humanity and injected each scene with a pulsating, ecstatic energy.

With Moriyama’s encouragement, Kitajima began to expand his practice beyond Tokyo. Having previously found inspiration in Shinjuku’s sordid and vibrant nightlife, in 1980 he turned his attention to the red-light district of Koza, a city in Okinawa Prefecture. The United States had established an air base at Kadena, also in Okinawa, at the end of World War II, and in 1970 Koza had been the site of a violent protest against the ongoing American military presence. Kitajima’s photographs in Photo Mail from Okinawa capture the wild and tense interplay of sex, money, and cultures that continued to mark the interactions between Japanese citizens and American soldiers ten years later. His work also took him to New York, where he photographed the height of 1980s decadence and excess both in black and white and in color. Not inhibited by his outsider status, Kitajima came right up to his subjects in the city streets, as he had in Tokyo. This direct engagement is often evident in the pictures, which were published in 1982 to great acclaim: New York earned Kitajima the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award, and it was even adapted for a 1995 Comme des Garçons fashion advertisement campaign.

In 1990 Asahi Shimbun newspaper, which founded the Kimura Ihei Award, commissioned Kitajima to travel throughout the Soviet Union to photograph the multiplicity of people and places across its numerous republics. The artist created an extensive visual document of the USSR on the brink of change—the state was officially dissolved on December 26, 1991, just one month after he finished shooting. This fortuitous timing lends considerable historical gravitas to the series, USSR 1991, and has greatly influenced the way the photographs have been interpreted. Often visibly exhausted, several of the pictured individuals clutch relics of earlier cultural and national identities, foreshadowing the seemingly inevitable fragmentation of the state. While Kitajima’s landscapes depict a utopian ideal in clear decline, his sympathetic portraits capture a resilient and diverse population.

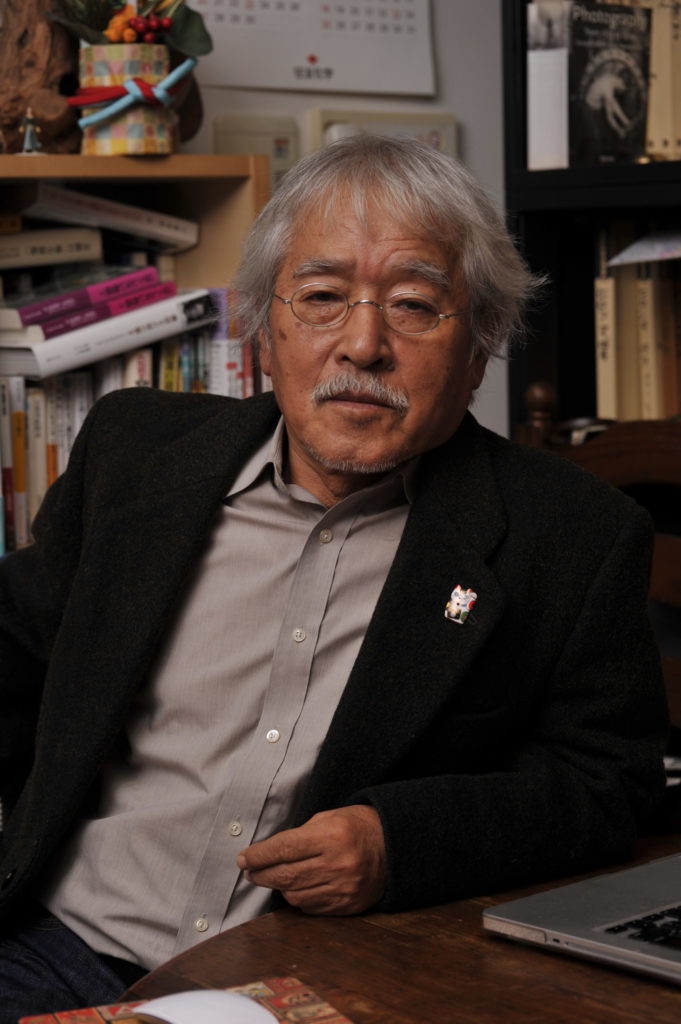

Today Kitajima remains an active and prolific member of Japan’s photographic community. He has largely transitioned from street to studio photography and has been working on an extensive, ongoing series of portraits of men and women and their built environments that has been exhibited frequently over the past twenty years. His interest in supporting younger photographers has also persisted: in 2001 he founded photographers’ gallery, a hybrid artists’ cooperative, exhibition space, and publishing house in Shinjuku.

— Matthew Kluk