The end of the 1950s and the early years of the following decade marked an astonishingly rich transitional moment in the history of photography in both the United States and Japan. While a long tradition of photography existed in Japan before this period, the country’s relationship with the U.S. after World War II seems to have instigated a distinctive and wide-ranging reexamination of the medium—a reaction against classic photojournalism and prewar aestheticism in favor of more personal and expressive picture making. Several key exhibitions in the United States in the 1970s drew attention to these shifts, highlighting not only new currents in Japanese photography but also the important ties between Japanese photographers and the Americans who were looking at their work with interest.

By the 1970s Japan had fully recovered from its postwar economic hardships and was experiencing a period of prosperity that would lead to the “bubble economy” of the 1980s. The abundance of the times and the lifting of restrictions on travel inspired a generation of young people to leave Japan and go abroad—often to the United States. Among them were photographers such as Eikoh Hosoe, who visited the U.S. frequently (he spoke fluent English, which was extremely useful); Ikko Narahara, who stayed in America for four years and studied with Diane Arbus; Ken Ohara, who has lived and worked in the U.S. since 1962; and Kikuji Kawada, Keizo Kitajima, and Takuma Nakahira, who traveled to Europe and mainland Asia. These excursions, often lasting years, were part of a larger surge of exploration of the U.S. and Europe by Japanese artists in many media.

The issues that occupied Japanese photographers during this time and the ways they engaged with them were in some cases responses to The Family of Man, a landmark exhibition organized by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, that traveled to Japan in 1956.[1] The show included 503 photographs made in 68 countries—mainly journalistic works, presented with the intention of generating a sense of world community and of drawing attention to the dangers of waging war in the new atomic age (fig. 1). Edward Steichen, the charismatic director of MoMA’s photography department, asked for Yasuhiro Ishimoto’s help with the Japanese version of the show, having previously met the photographer and displayed his work at the museum. Ishimoto’s role, however, was ultimately minimal; instead he became a central figure in the transition of Japanese photography toward a new kind of expression.[2]

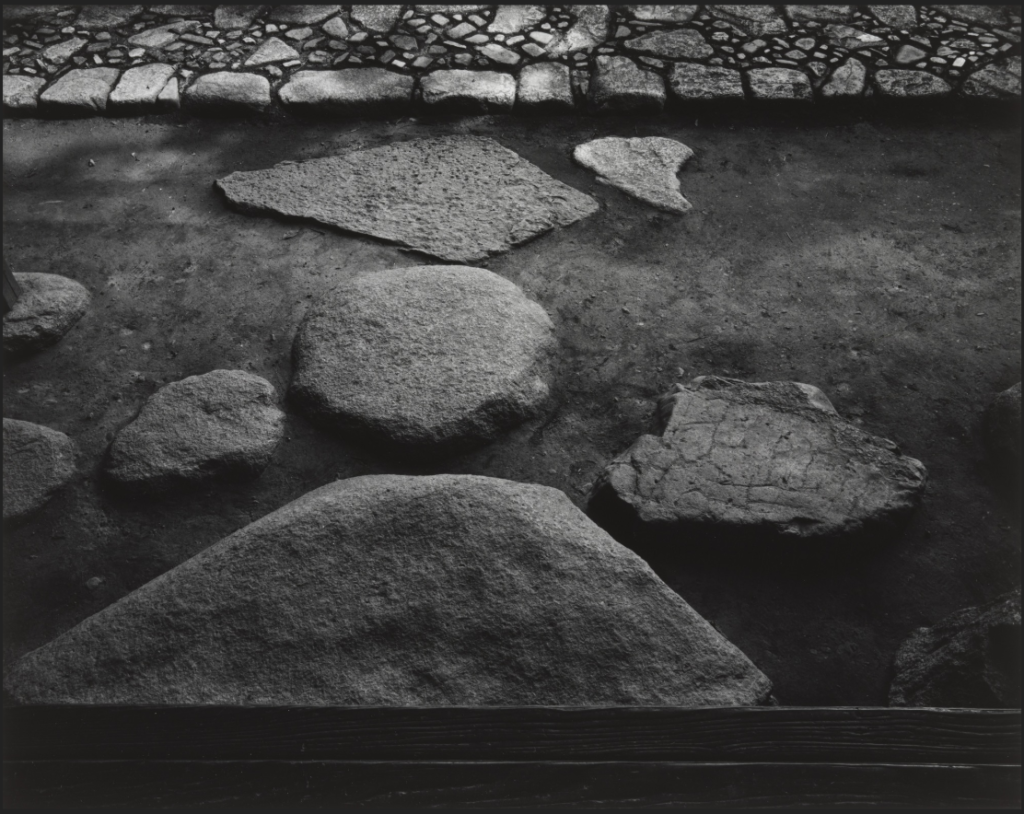

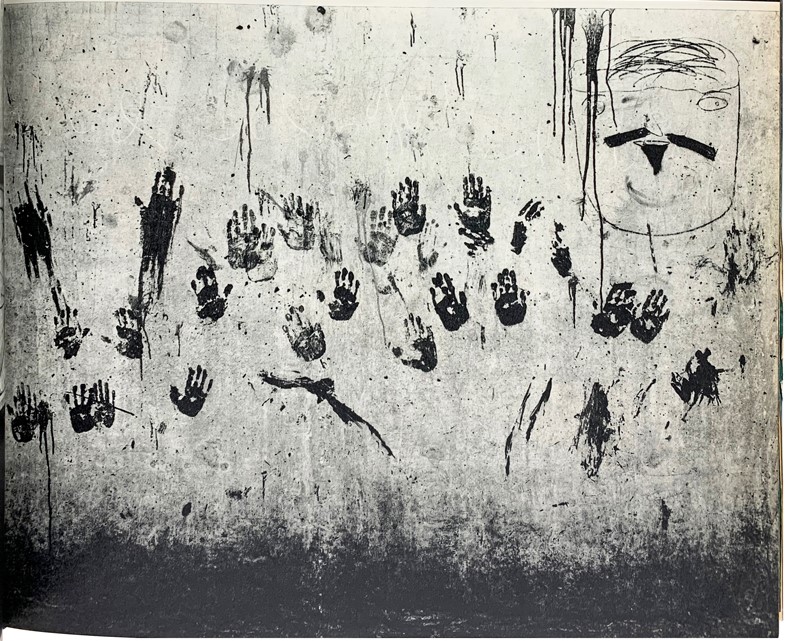

Born in San Francisco in 1921, Ishimoto was an outsider in Japan, where he moved with his family in 1924. He returned to the U.S. in 1939 and was incarcerated at Amache, a Japanese internment camp in Colorado, during World War II. It was there that he learned photography, which he went on to study with Harry Callahan at the Institute of Design in Chicago after his release. Although his central legacy would be his elegant modernist pictures of Tokyo and traditional Japanese architecture (fig. 2), his most compelling and original works describe life in Chicago (fig. 3), where he responded to everything from the imaginative play of children in the city’s Black communities to people enjoying the pleasures of the local beach. Ishimoto moved back to Japan in 1953 and would remain there save for a second stay in Chicago from 1959 through 1961. His work was frequently published in Japanese photography magazines, especially Asahi Camera and, later, Camera Mainichi, and he became affiliated with other young photographers whose pictures appeared in those periodicals, including Narahara, Hosoe, and Shomei Tomatsu. Some of his pictures were included in The Family of Man, but, as a modernist, he also participated in and helped organize a more innovative annual exhibition called The Eyes of Ten, the first installment of which was held in 1957. Its accompanying pamphlet declared, “The world of photography is changing in a major way. It is a time when everyone must think about the future of photography.”[3] In 1959 a group of emerging talents, some of whom contributed to The Eyes of Ten—Hosoe, Kawada, Narahara, Akira Sato, Akira Tanno, and Tomatsu—formed VIVO, the first Japanese cooperative (based loosely on Magnum) to promote a radical, raw, and individualistic alternative to conventional journalistic photography, signaling the real beginnings of modern photographic expression in Japan.[4] Most of their work examined the social conditions of the country in personal, emotionally striking ways that were antithetical to the older documentary style and optimistic politics of The Family of Man.

Photography in the United States was also changing. In 1962 John Szarkowski succeeded Steichen as director of the photography department at MoMA. Szarkowski demonstrated a keener attention to the particular properties of the medium than did his predecessor. While his early exhibitions at MoMA included a show about the transformation of photojournalism, which studied the changes activated by television, Szarkowski examined photography more broadly and from a formalist perspective: looking at vernacular pictures, works made by a child (the gifted Jacques-Henri Lartigue), scientific photography, and even pictures made by ATMs. By hosting such exhibitions, MoMA fostered the evolution of the medium into a form of art with its own unique characteristics, history, and important practitioners.

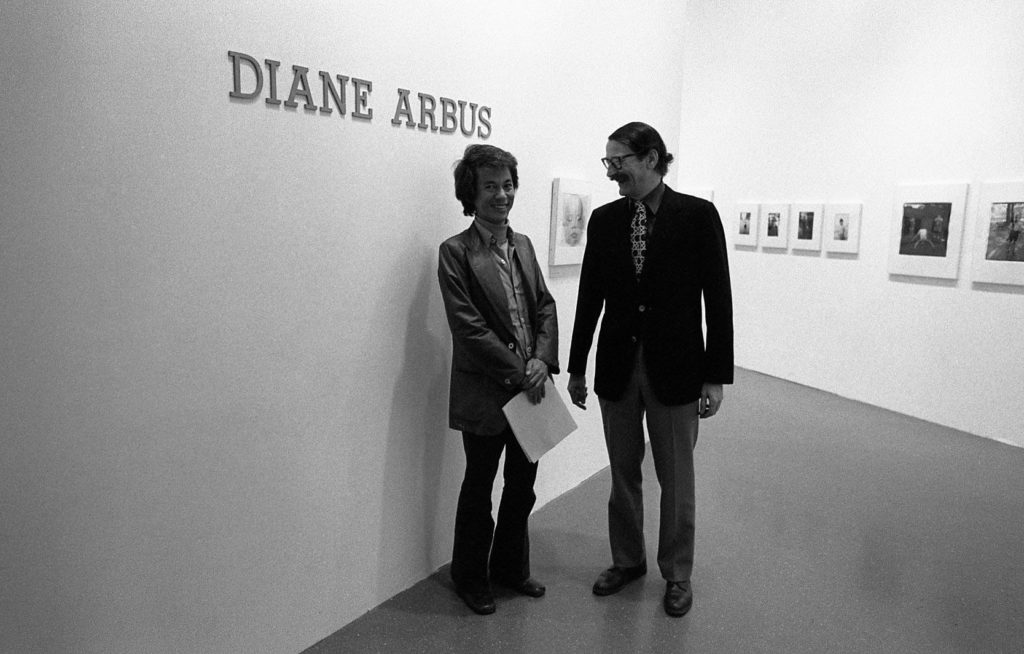

The first international institutional recognition of the significant creative activity in Japanese photography was MoMA’s show New Japanese Photography (March 27–May 19, 1974), organized by Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi. Although Szarkowski had been considering such an exhibition since shortly after his arrival at the museum, it took some time to produce, and after it closed MoMA did not pursue the subject again until much later, after Szarkowski’s retirement. An earlier presentation, The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture, held in 1966–67, indicated the museum’s interest in Japanese art, but it focused on examples of abstract expressionist painting, a style closely associated with American artists. The 1974 show was a truer reflection of the distinctive and innovative Japanese aesthetics of its time.

Since Ishimoto had maintained contact with MoMA’s photography department, Szarkowski wrote to him on July 29, 1970, about his plans for the show: “I envision the exhibition not as an exhaustive survey,” he stated, “but as one that will concentrate on the work of a relatively few photographers of exceptional significance in Japanese photography during the past twenty years. I suspect it is true in Japan, as it is here, that the popular magazines do not necessarily give an accurate sense of the most original and vital work being done, and I am, in effect, asking your suggestions as to the names of those photographers whose work I should see before determining the content of the exhibition.”[5]

Szarkowski went to Tokyo in 1971, staying for about two weeks. Besides meeting with photographers, he visited the offices of Camera Mainichi to study the pictures that had appeared in its pages and came to know its editor, the charismatic Yamagishi (fig. 4). It became clear to him that the magazine was the most engaged venue for recent photography in Japan, though not the only one, and that Yamagishi was a chief defender and an eloquent supporter of the new work that was being produced: the corporate owners intended Camera Mainichi to serve the lucrative amateur market, but Yamagishi had made it a venue for a modern and distinctive art.[6]

The work that interested Szarkowski turned out to be a departure from Ishimoto’s Chicago-inspired pictures. With Yamagishi’s help he focused his attention on a group of younger photographers that the magazine especially highlighted. Though Ishimoto’s role in the exhibition became less important and he was, in the end, presented as a member of the older generation, the curators acknowledged him as a figure of pivotal importance. In his catalogue introduction—there are two, the other written by Szarkowski—Yamagishi notes: “Many of the essentials of modern photography were learned in the postwar period from Yasuhiro Ishimoto, who brought them from the United States when he returned to Japan. Although it might have been possible to learn the philosophy and techniques of modern photography from someone else, I would like to make clear that without Ishimoto we would never have achieved today’s photography.”[7]

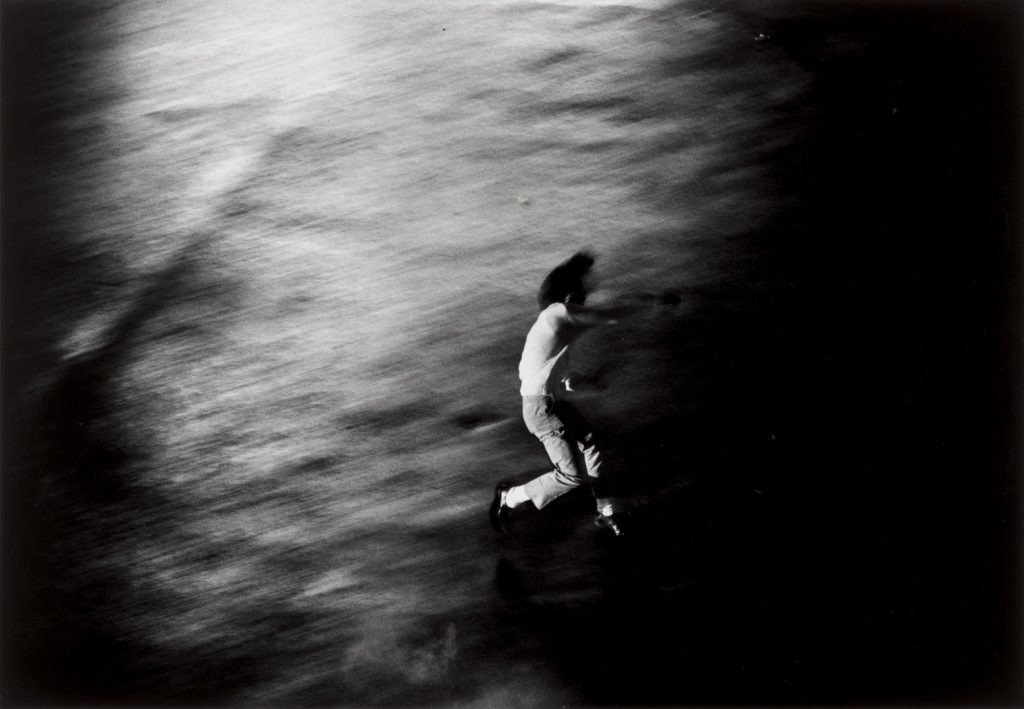

The photographers who dominated the show were Tomatsu, whom both organizers recognized as a seminal figure, and Daido Moriyama, his younger colleague. Yamagishi and Szarkowski saw that Tomatsu and Moriyama’s great contribution was a new aesthetic that nonetheless evolved from journalism. Szarkowski wrote in his introduction: “The highly individual character and meaning of Tomatsu’s work . . . was not the rejection of traditional journalism but the acceptance of a larger and more difficult problem that defines Tomatsu’s identity as a photographer. The problem was perhaps the rediscovery and restatement, in contemporary terms, of a specifically Japanese sensibility.”[8] Tomatsu’s main and guiding subject was the role of American foreign policy in Japan and the ambiguous presence of Americans in his country (fig. 5). As Yamagishi noted, “It is apparent that his photographs are not an objective record of what happened.”[9] One of the few participants in the exhibition who had never visited the U.S., Tomatsu produced resonant, subjective descriptions of a culture in transition. Moriyama, on the other hand, was enchanted with the work of Andy Warhol and with the expressive, dark energy he saw in William Klein’s vision of New York. He appropriated both into his own emotionally inflected view of Japan and its ambiguous relationship to the culture and political power of the United States.

The other major venue for exhibitions of photography in New York was the International Center of Photography (ICP). This institution had a rather long gestational period. After the war photographer Robert Capa stepped on a landmine in Vietnam in 1954, his younger brother, Cornell Capa, took it upon himself to preserve and publish the work Robert stood for. In 1967 Cornell organized The Concerned Photographer, a presentation of pictures by Robert and his associates at Riverside Museum in New York; a version of the show opened in Tokyo the following year and toured Japan.[10] In 1974 Capa established ICP, an exhibition and teaching facility housed in a converted mansion on Fifth Avenue. Though his access to funding was usually precarious, Capa actively expanded his program beyond the core group of Magnum photographers with whom he had started in order to include other photographers with decidedly humanist sensibilities. Capa’s particular interest in photography and exhibition prospects in Japan was in concert with his interest in W. Eugene Smith, who had spent significant time in the country, married a Japanese American woman, and in 1971–73 lived in the city of Minamata to photograph the effects of industrial mercury poisoning on its fishing community (fig. 6).

In 1978 Yamagishi and Capa were in communication about an exhibition at ICP for which they would engage a steering committee of contemporary Japanese photographers: Hiroshi Hamaya, Jun Miki, Tomatsu, Narahara, and Ryoji Akiyama.[11] On July 31 Capa wrote to Yamagishi, apparently after a visit by both Yamagishi and Akiyama to New York, setting forth an agreement with the cautionary sentence, “We have agreed to move on with the project even though the $40,000 provides less than the barest minimum to complete the gathering of material and producing an edition of the book.” Yamagishi would be the “chairman of the committee to collect the material” and the editor of the exhibition catalogue. Capa would come to Tokyo in October 1978 to review the materials, and Yamagishi would visit New York in early February 1979 to finalize the project and go to press. Capa then wrote: “The theme of the exhibit is: JAPAN: A SELF-PORTRAIT. It is documentary, but this must not be taken too literally. The photos can/should express a frame of mind, a cultural attitude and the coverage can be of the past fifty years.” He also mentioned incorporating the presentation into a larger exhibition he was organizing in Venice in 1979—an important opportunity for a European version of the show, but one for which they would need extra funding.[12]

On September 29, 1978, Yamagishi wrote to Capa that the committee had met and determined that the show should be restricted to work of the 1970s, rather than offering the broader historical overview they had originally considered. “Furthermore,” he noted, “the year 1979, the year the show is held, is the last year of ’70s, and there have been lots of occurrings [sic] in our photographic scene since MoMA’s New Japanese Photography in 1974, which represented Japanese photos produced mainly in [the] 1960s.”

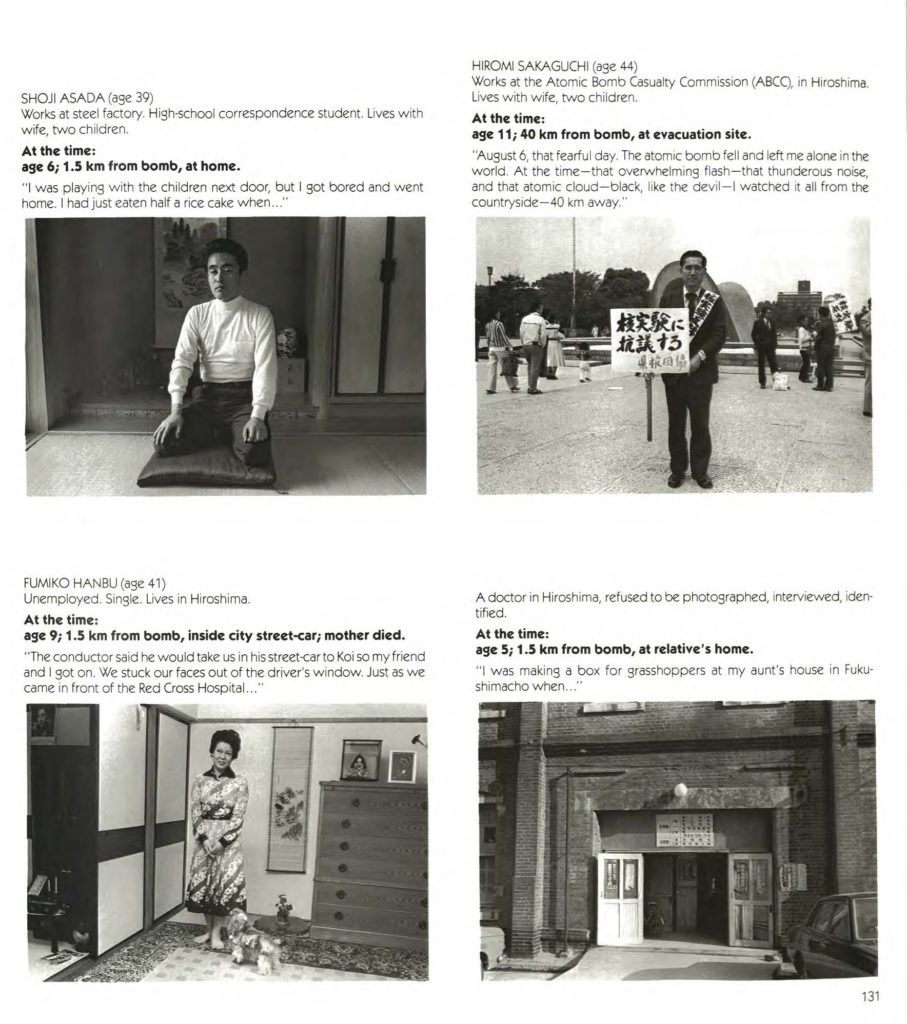

In November an article with a picture of Capa and Yamagishi appeared in the Mainichi Daily News, announcing the show as part of a larger program scheduled for spring 1979: “‘Japan Today,’ a continuing celebration honoring the cultural, intellectual, and economic life of contemporary Japan, will be held with major events in New York, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Denver and Los Angeles.”[13] The participants in the ICP exhibition, Japan: A Self-Portrait (April 27–June 3, 1979), included Akiyama, Taiji Arita, Nobuyoshi Araki, Masahisa Fukase, Hamaya, Shinzo Hanabusa, Miyako Ishiuchi, Kawada, Jun Morinaga, Moriyama, Narahara, Kishin Shinoyama, Issei Suda, Tomatsu, Haruo Tomiyama, Tsuchida, Shoji Ueda, Gasho Yamamura, and Hiroshi Yamazaki. The show would be more diverse and adventurous—and it would expand further beyond documentary photography—than the exhibition Yamagishi had co-curated with Szarkowski. It lacked the earlier realism of Ken Domon and the formalist pictures of Ishimoto, both featured at MoMA, and incorporated a wider variety of work, much of which was quite strange by American standards of the day: appropriated, double-exposed, eccentric photographs by Kawada; Tsuchida’s Children of Hiroshima: 33 Years Later, for which he photographed and interviewed people who had been directly affected by the atomic bomb (fig. 7); and abstract, manipulated seascapes by Yamazaki (fig. 8), who was known as an artist in other media but not as a photographer. Color prints, a NASA picture of the island of Kyushu, work by a woman photographer (Ishiuchi), and other such inclusions made the ICP exhibition more expansive, and perhaps more Japanese, than the MoMA show.

Many American photographers visited Yamagishi in New York during the winter of 1978–79, as he was finishing the catalogue and final preparations for the show were underway. Frequent visitors included Lee Friedlander, Richard Avedon—with whom Yamagishi traded an expensive jacket—and Bruce Davidson. All were delighted by Yamagishi’s ebullient personality.[14] The exhibition was successful in New York and an abridged version continued on to Venice, but the exhausted curator returned to Japan, requesting from Capa the payment he had promised the photographers.[15] On July 4, 1979, Yamagishi wrote to Capa congratulating him on the Venice show as it was closing, but there were some problems, and the letter becomes essentially a list of complaints: the photographers had still not been paid, and funds to print the catalogue had not been provided yet either. Further, a carousel of slides by Moriyama had been stolen, though neither Moriyama nor Yamagishi had been notified when it happened.[16] There was more. Fiscal anxiety seems to have afflicted Yamagishi ever since he resigned from Camera Mainichi to become an independent curator, as he ultimately lacked the financial and institutional support of his American counterparts, such as Capa and Szarkowski. Admitting that his tone was “brusque,” Yamagishi soon slid into a depression and died on July 20.[17]

After Yamagishi’s death the steering committee for Japan: A Self-Portrait met to discuss whether the exhibition should come to Japan, as Capa proposed and earnestly desired, in part as a memorial to his friend. Although almost everyone was willing—probably both out of affection for Yamagishi and in thanks for Capa’s efforts in making the show happen—there was one holdout. Tomatsu wrote in a letter to Capa that while they were organizing the exhibition, Yamagishi had told him that if it were presented in Japan, his choice of works would be different. The agreed-upon selection was for Europe and North America only. Tomatsu concluded by saying: “I am grateful as a friend of Shoji for your offer to open the exhibition in Japan in order to reward Shoji’s efforts. But, I think the contribution of Shoji, who lived for photography, was obsessed by it, and died burning out his energy, cannot be measured by Japan: A Self-Portrait alone. This show happened to be his last work, but he had created many other significant exhibitions and publications in his lifetime. If it is possible at all, the best way to honor Shoji would be to have an exhibition or a publication that would rightly represent his life work. I hope you understand.”[18] This, of course, never happened.

New Japanese Photography and Japan: A Self-Portrait occurred at a critical moment for the medium in Japan. National institutional support for photography was part of a larger conscious effort to recharge the country’s industry in the postwar period, when—aided by American policies—it was developing a strong consumer economy. From this imperative the photographic community in Japan expanded, as it did in the U.S. and Europe, exuberantly superseding the limited expressive range of classic photojournalism and conventional amateur practice. These exhibitions placed Japan’s new and unique contributions to picture making on an international stage, and, as manifestations of a committed interest in the medium, they helped inspire the country’s industrial and cultural leaders to eventually found a national museum of photography. Even today, despite increased globalism, Japanese photography remains a vital and distinctive art form, a product of its postwar history.

Notes

- See my essay, “Currents in Photography in Postwar Japan,” in Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of the Nation, by Leo Rubinfien, Sandra S. Phillips, and John W. Dower (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 47–51.

- While Steichen was primarily interested in the message of The Family of Man, especially in Japan, he was also committed to fostering the art of photography as practiced by Ishimoto. He included Ishimoto’s work in a three-person exhibition at MoMA in 1961.

- See Iizawa Kotaro, “The Evolution of Postwar Photography,” in The History of Japanese Photography, by Anne Wilkes Tucker, Dana Friis-Hansen, Kaneko Ryuichi, and Takeba Joe, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003), 217. Ishimoto did not participate in the second installment, which comprised only color photographs and was held in July 1958, as he was preparing to leave for the United States on a fellowship granted by the Minolta Corporation.

- See Marc Feustel, “Staring at the Sun,” in Nihon no jigazo: shashin ga egaku sengo 1945–1964 / Japan: A Self-Portrait, Photographs 1945–1964 (Tokyo: Kurevisu, 2009). Feustel makes the point that the VIVO photographers came out of journalism and transformed it. He notes that Narahara characterized his 1956 exhibition Human Land as aiming “for a method that might be called a personal document.” Ibid., 19.

- Letter from John Szarkowski to Yasuhiro Ishimoto, July 29, 1970, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, Photography Department, Yasuhiro Ishimoto file. Szarkowski undoubtedly saw the January 1962 issue of Camera magazine, which contains one article by Hiroshi Hamaya and another by Kazuo Okamoto called “The Present Situation of Japanese Photography,” as well as—more importantly—the September 1966 issue, with a cover and portfolio of pictures by Narahara, work by other Japanese photographers, and texts by Yamagishi and other Japanese critics. Published in Switzerland, Camera was one of the most beautiful and thoughtful photography magazines of this time.

- In my conversations in the 1990s with Yamagishi’s widow, Kyoko (Koko) Yamagishi, she often said that the prime cause of tension between her husband and the owners of the magazine was their insistence on giving primary attention to the large amateur audience. See also Edward Putzar, Japanese Photography 1945–1985 (Tucson, AZ: Pacific West, 1987), 16 and 49.

- Shoji Yamagishi, “Introduction,” in New Japanese Photography, ed. John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1974), 12.

- John Szarkowski, “Introduction,” ibid., 10.

- Yamagishi, “Introduction,” 12.

- The Riverside Museum, which is no longer extant, was affiliated with Riverside Church, a large, interdenominational Christian church near the main campus of Columbia University that was (and remains) engaged with social justice causes. The Concerned Photographer was presented at the Matsuya department store in Ginza, Tokyo, from August 9 through 21, 1968. It consisted of about 350 photographs. The rather classical selection of photojournalistic work was augmented with pictures by André Kertész, who had contributed to early illustrated magazines in prewar Paris but otherwise could not be described as a journalistic photographer. Demonstrating the fluidity of the relationships between photojournalists and those more inclined toward fine art, one of Smith’s assistants in Japan was Jun Morinaga, an art photographer whose work Yamagishi would later include in Japan: A Self-Portrait. Smith was a great admirer of Morinaga and wrote a blurb for his book River, Its Shadow of Shadows (1978).

- Letter from Shoji Yamagishi to Cornell Capa, February 3, 1978, International Center of Photography Archives. Capa wrote back to Yamagishi on March 21, 1978, noting that the Japan Society had said that “the project is on” and that Capa planned to come to Japan no later than September to work with him. All of the following quotes from letters to and from Capa and related materials are in the ICP Archives.

- Capa mentioned that they were looking for another $80,000 and that they had received some money from the National Endowment for the Arts, from which a portion of Yamagishi’s fee would be paid.

- “Photo Exhibition—Self Portrait: Japan,” Mainichi Daily News, November 15, 1978, ICP Archives. Needless to say, the quoted description of “Japan Today” was more aspirational than accurate.

- This was recounted by Yuriko Kuchiki, Yamagishi’s assistant for the show and a resident of New York since those years. Conversation with the author, February 18, 2018.

- Telegram from Shoji Yamagishi to Cornell Capa, May 25, 1979. It is clear from their correspondence that there was never enough money for the show. In this telegram, Capa notes that he is about to leave for Venice, with regrets to Yamagishi that he won’t be coming along.

- “Moriyama is worried that the ICP considers this a theft of the carousel rather than of his work. I would like to know what reparations and solutions you have in mind.” As it happens, Moriyama has no recollection of his slides having been part of the show. It may be that they were only part of the Venice exhibition. Daido Moriyama, conversation with the author, summer 2018.

- There is a letter dated July 25, 1979, from Kyoko Yamagishi to Capa regarding the unbound copies of the catalogue that remained after her husband’s death, as a publisher had not yet been identified. In a letter to all of the photographers dated March 26, 1980, Capa states that the show had been a success in New York, Venice, and Torino, and that it was currently enjoying similar success in Albuquerque, after which the pictures would return to Japan, along with checks. “We very much regret the confusion concerning this payment, and hope that everything has now been settled to your satisfaction.” In a memo to the “Japanese Committee” dated August 12, 1980, Capa expresses his hope that the show will go to Japan.

- Letter from Shomei Tomatsu to Cornell Capa, June 18, 1980. Translated by Yuriko Kuchiki.