primary source

“Dialogue: In Search of Another Hand”

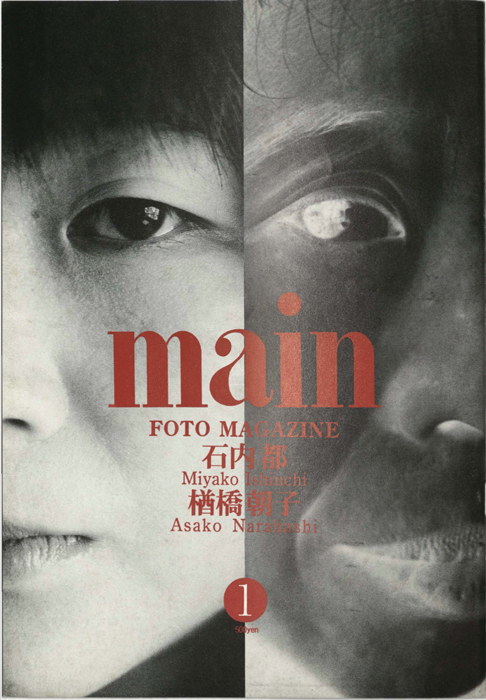

Main

Miyako Ishiuchi and Asako Narahashi

- original document

- Japanese

- publication type

- article

- publication date

- 1996

This document file is downloadable in the original Japanese, with the English translation below.

“Dialogue: In Search of Another Hand”

Main 1 (March 1996): 10–15

We created this journal’s name by joining the initials of our names, I. M. and N. A. If you rearrange the letters, it spells out the French word for hand, MAIN. With this journal, we want to create a space that is different from what is offered at photography exhibitions. We are aiming for ten issues in total. The following is a dialogue on the occasion of the first issue.

[Miyako] Ishiuchi: Why and when did you become interested in photography?

[Asako] Narahashi: This happened in multiple stages, but the awareness that I was doing photography dawned on me around 1986. I was working for the journal Shashin Jidai (Photography Age),[1] where they had a project called Foto Session.[2] I rarely looked at photography journals, myself, but on that occasion I bought a camera and began going on walks to take pictures.

Ishiuchi: When Shashin Jidai first came out, I was working on the exhibition From Yokosuka, which took place in a dilapidated former cabaret on Dobuita Street in Yokosuka. I remember well how Akira Suei, the chief editor of Shashin Jidai, stopped by the opening party. He had been in the area because he had wanted to meet with Daido Moriyama, who lived in Zushi. At that time, I was surprised when somebody told me that even though Shashin Jidai called itself a photo journal, it was actually an erotic magazine. But I imagine you probably also thought of it as a journal of photography?

Narahashi: That is true. Well, I found it interesting, at least in part.

Ishiuchi: They were scrambling together every aspect of photography, including subjects and formats. They would have a photo by [Nobuyoshi] Araki of a nude girl with her legs spread open, and on the next page there would be one of Moriyama’s somber, introspective shots in black and white. The journal’s intrigue lay in its sheer novelty. It is curious that a journal like this was one of your inspirations to get into photography. But how was it working with Foto Session?

Narahashi: We had kind of a hideout in Nishi-Shinjuku. Apart from our regular meetings on the first of each month, we used it as a darkroom. There were many who only came for the regular meetings, but I moved to a place only three minutes away, walking distance, so I used the darkroom frequently. We had to move out of our secret base two years later, but thinking back on it, it really felt like a place of origin. It was not a place to do exhibitions but to chat about photography and develop prints.

Ishiuchi: The word hideout is so nostalgic. It sounds like you’re talking about an underground political group. When I started photography, I participated in a group exhibition called Photographic Effect.[3] The venue was in Shinjuku, so I would also often come to the area and hang out in the bars afterward, drinking and talking about photography. It seems we’re all quite similar when we’re just starting out. But I don’t see anyone from back then anymore.

Narahashi: You also had such a phase? You always seem to work on your own, so I’m surprised to hear that.

Ishiuchi: The first time I went to see Photographic Effect, it was just as a visitor. But then Yada Takashi suggested I try photography myself. So I started out without expecting anything. Then, within two months of getting myself a camera, I would already be featured in the exhibition. I thought Yada was pretty bold to feature me.

In Photography, People Judge You Based on Where You Exhibit

Ishiuchi: To stick to doing your own thing—be it economic freedom or choice of exhibition venues, I always thought it was amazing how you succeeded in creating your own spaces, making your own photographs in your own space. That you were able to do that got me curious.

Narahashi: In the beginning though, I had no place that was properly my own. Only after 801,[4] Kaido,[5] M,[6] and Hokuten[7] opened did I think I should try something like that myself. In October 1990 I opened 03 Fotos, which was a good move, but the location was inconvenient, and compared to my time at Kaido, there were very few visitors. Of course, it was not the main goal to have many visitors, but at times I felt isolated, just sitting there by myself.

Ishiuchi: But you also lend this space to others, no? What are your criteria for having others exhibit at 03 Fotos?

Narahashi: I feel puzzled, or rather bewildered, whenever other artists approach me. Like, why does this person want to exhibit their work here? I don’t mean to say that my place is insignificant, but I wonder whether the people who come in actually understand its purpose. In terms of criteria I set for those I let use the gallery, I honestly don’t care much about works by others, so I don’t know. I would feel arrogant judging them myself. Whether they have enough ambition, or whether they can express themselves genuinely—that’s really all there is. And it has to be someone who understands the meaning of this space. I don’t like it when people come in and expect it to fit neatly into just one category, like an artist-run gallery or commercial gallery.

Ishiuchi: When I had my first solo exhibition I chose the Nikon Salon, which at that time was in Ginza, for two reasons—it was large and had many visitors. Initially, I wanted as many people as possible to see my works and to show as many works as possible. Thinking about it, I’m actually impressed I managed to get such a huge space. Back then, I didn’t properly consider the grandness of the space; I just relished the thought of completely filling it with photographs. The Nikon Salon in Ginza was my starting point, but nowadays these huge venues scare me. Or rather, I prefer to have fewer works or, if it’s going to be a big venue, then to make it a massive one but show just one single work. Youth is a kind of force, and this force allowed me to produce many works in large sizes without ever getting exhausted. I don’t have that physical energy anymore, and this, of course, affects the character of my work. But I am still the same person. On the surface it may appear that my focus has completely shifted, and indeed, I do think about the individual photograph differently now.

When I exhibited Yokosuka Story, I stuck the photographs onto the wall with double-sided tape. In hindsight, it was awful and made my works look pathetic. One hundred eighty prints stuck straight on the wall with that rough tape. When we took down the exhibition, we had to pile the prints up back to back [because the tape still stuck to them].

Narahashi: Seriously, mounting prints directly onto the wall? Even I don’t do that.

Ishiuchi: I wanted to make them look like part of the wall, hence the double-sided tape. I considered my photographs to be like objects in those days.

Narahashi: But you got into a bit of trouble at the Nikon Salon during that time, isn’t that correct? Or maybe trouble isn’t the right word—

Ishiuchi: Well, right now we’re in the midst of a recession, so it is getting more difficult for the manufacturers of photographic equipment, but in those days it was a different story. When I stuck my prints directly onto the wall with tape at the Nikon Salon, initially no one objected. When we dismantled the show there were still all these traces of tape left on the wall, and the owner demanded compensation, because they had to repaint everything. But they had agreed beforehand to let us do this, so in the end I got away with paying nothing. In those days, there was more leeway.

Narahashi: This was about twenty years ago, right? Even those who are opposed to corporate patronage nowadays might have exhibited their works there. I have never thought about holding my exhibitions at corporate-owned galleries because it sounds like you have to go through a lot of nuisance. You submit your work to the selection committee and then have to wait an eternity for them to make a decision about whether they want to feature you or not. And in the meantime, I would have already changed my mind about it.

Ishiuchi: On the contrary, back then there were so few galleries that showed photography that it was actually possible to enjoy the screening process. Today there are of course more venues. However, in photography or any other art, people will judge you based on where you exhibit. You created your own space, so I assume you don’t have to deal with that anymore. Are you freer to do what you want?

Narahashi: I wish I were able to do whatever I felt like. It seems of all possible things I am able to do in theory, there are not that many I actually want to do.

Ishiuchi: How many exhibitions have you organized so far?

Narahashi: Twenty-two in the last five years. Actually, adding it up, maybe thirty-two in total. Keeping my bio up to date is kind of a nuisance. I prefer to keep it simple.

Ishiuchi: Don’t abbreviate here. You must have quite an impressive collection of invitation cards.

Narahashi: I usually throw them away afterward. I might have kept a few somewhere in my place. I would have to look for them.

Ishiuchi: Please don’t throw them away. Like it or not, they’re like history. I enjoy those cards; they make much better history than regular artist CVs.

I Don’t Want to Create Only Serious Photo Books but Also More Light-Hearted Publications

Ishiuchi: For this first issue of MAIN, I’m planning to include photographs I took of my father. I started to photograph him after he was hospitalized. He was in the hospital for just two weeks, and it was my first time taking photos of him. My new book, Sawaru: Chromosome XY (Touch: Chromosome XY; Foto Muse, 1995), includes only portraits. I thought I had almost missed the opportunity to ever have him in my pictures. So I went to see him every day: in the morning, at dawn . . . I would open the curtains when it was getting light; in fact, I stayed over at the hospital most of those nights. When I began to capture him, I first shot his hands and feet. I noticed the color of his skin was slowly changing. His fingertips were getting colder. So cold that I thought he would die. He heart was beating, but the blood didn’t seem to circulate. When my mother grasped his hand, I took one picture that I thought might just become a masterpiece. I remember how I asked my mother to hold his hand even tighter [laughs]. It’s not sad as long as we keep taking pictures, right? I get easily excited when I’m taking pictures. And while taking the pictures I kept talking to him, saying, “You will get better soon.” He seemed unconscious and was on artificial respiration, but I believe he somehow sensed I was there taking photographs.

Narahashi: Those are pictures we seldom get the chance to take, aren’t they? But in such a situation, I assume you forget you’re capturing someone’s imminent death, and taking pictures comes rather naturally?

Ishiuchi: Normally I’m too embarrassed to take pictures of my relatives. Since Yoko died—one of the women I photographed for my book 1∙9∙4∙7—I haven’t looked at those images. I haven’t looked at the last shots I took of my father for Sawaru: Chromosome XY since he died. In that sense, there is a strange correspondence between my previous and current books.

Narahashi: I published a series, Nu-E, in Nippon last year and am currently thinking about continuing it. The images were published on two-page spreads over a few issues, but there were many who criticized me, saying that the images were not suited for a journal. Or perhaps they were not strong enough, so it was my fault—I’m not sure. In this magazine, I can use up as many pages I want, so I can’t make any excuses.

Ishiuchi: We began to collaborate on this project randomly, because I also thought I had to do something different. When you prepare for exhibitions, you concentrate fully and go to the darkroom, which for photographers is an everyday thing. But still, there remains a flavor of doing something unusual. I concentrate fully when developing prints, but afterward I feel a need to get into a different mood. It’s like a natural backlash against that state of being submerged in the process of creating original prints. I wonder if this is a bit shallow, but I don’t want to only create serious photobooks—I also want to engage in more light-hearted types of publication.

Narahashi: What a coincidence! So far I have not published any photobooks, though I definitely want to have one soon. But so far, financially speaking, it has seemed impossible to do both. I want to do something that emphasizes my working process, so I was thinking of creating something ongoing, like a journal, even if it didn’t have that many pages. In any case, I don’t want to end up with something cheaply produced, so I want to limit this kind of activity to two publications a year at maximum. Including our project, MAIN, of course, I can raise it to three times, because we are doing this together. Since before the summer, when we began to plan this, so many things have opened up. If I were alone, I would get stuck so many more times with all the obstacles we faced.

Ishiuchi: You’ve got keep on trying new things and expanding, or else. It will immediately show. Even when you publish at your own expense, people ask about your motivations.

Narahashi: I think self-publishing is the only thing that makes sense for MAIN. When you publish with your own money, you are no longer under any constraints. You stand on your own feet. I mean, financial limitations, of course, continue to matter. To be honest, because of MAIN, I’m in a tight situation now. We joined our energies, but we’re only two. On the other hand, doing what we want, the way we want, is something I find extremely fulfilling.

Ishiuchi: In the past there seemed to be more people thinking like this. Two great examples were Moriyama’s journal Kiroku (Record)[8] and the journal Provoke,[9] which was run by a group of artists. We do things our own way!—that was the attitude. At the same time, it was an obvious expression of their frustration with society.

Narahashi: I found it cool.

Ishiuchi: I totally agree. Recently, young people engaging in these new projects [picks up a copy of Kaiten (Revolve)[10]] have used print as a tool of communication. I think they don’t just want new exhibitions or new original prints. They’re aiming for new methodologies. But they’re doing it in a casual manner, and I like that.

Narahashi: Casual, maybe, but not shallow. I appreciate what they’re doing.

Ishiuchi: I was maybe too serious in the past. To me, photography felt a like call of duty: I have to do something! Looking back now, I think this is what made me so serious. I felt like I was on a mission, not unlike the guys at Provoke. From today’s perspective, looking at the three issues of Provoke exhausts me. For better or worse, that photography journal was definitely a child of its time. And MAIN will be the same. We can’t escape our own time. Eventually, all printed matter becomes a part of history. But what we want is to have photography claim its place in the context of history.

Narahashi: Yes, and this is different from organizing photo exhibitions. Some say I learned to spread my wings by doing exhibitions. Let me put it this way: in addition to the places that were my “wings” in the past, I now want not just another “wing” but rather another “hand” [=MAIN].

Ishiuchi: I don’t usually exhibit in mainstream places; I think I resonate with a few particular places, like your exhibitions at 03 Fotos. Yet, in contrast to the original print that exists in small numbers and is somewhat elitist, print media allows one to reach an unlimited audience. And to me, this is just another amazing thing about photography.

Biographies

Miyako Ishiuchi

Born in 1947 in Gunma Prefecture, Ishiuchi grew up in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, from 1953 to 1966. In 1970 she dropped out of the textile course at Tama Art University. Ishiuchi worked in photography beginning in the late 1970s. Her first exhibited work was Invalid Darkness for the group exhibition Photographic Effect 3. After her first solo exhibition, Yokosuka Story, she worked on the series Apartment, for which she received the fourth Kimura Ihei Award. She concluded the trilogy of her first three projects with Endless Night. In her following works Ishiuchi focused on ephemeral sensations such as scent and the passage of time in urban spaces and on the surface of architecture. Since the 1990s she has focused on the human body. For 1∙9∙4∙7 Ishiuchi pictured the hands and feet of fifty women the same age as herself. In the early 1990s her works were shown in nine different cities across the world, yet no solo exhibitions in Japan took place. In 1994 Ishiuchi published 1906 to the Skin, a photo series of the butoh dancer Kazuo Ono, which was followed in 1995 by Hiromi 1955, a series on the poet Hiromi Ito, and To the Skin. She is currently working on a new project, Scars.

Asako Narahashi

Born in 1959 in Tokyo, Narahashi started to work with photography around 1980, using her own darkroom. In 1989, after graduating from the humanities department of Waseda University, Narahashi began organizing a series of exhibitions, Dawn in Spring. In 1990 Narahashi opened the independent gallery 03 Fotos. Since 1992 she has published the photo series Nu-E. She participated in the group exhibitions Foto Session 1–6 (1986–89, Shinjuku Culture Center and Place M), Six Days of Change (1987, Citizens’ Gallery at Setagaya Art Museum), and Trends of Contemporary Photography: Another Reality (1995, Kawasaki City Museum).

Notes

- Photo journal founded in 1981. Appearing monthly, the journal had a radical, sensationalist approach, publishing three major photo series by Nobuyoshi Araki and much of Daido Moriyama’s work. It went on hiatus in 1988; after two attempts to revive it, Shashin Jidai was discontinued in 1989.

- A project initiated by Shashin Jidai in 1986, coordinated by Noboru Iijima. The journal would assemble about a dozen photographers and hold monthly meetings chaired by Daido Moriyama. Foto Session would publish two photobooks in 1987 and 1988, respectively.

- The first Photographic Effect exhibition was organized in 1974 by Yada Takashi and Hachiro Hamada and included works by Takashi, Hamada, Ritsuko Kanbayashi, and Tsunehisa Kimura. The exhibition took place a total of five times, with participating artists such as Katsumi Watanabe, Hiroshi Yamazaki, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Osamu Takizawa. The exhibitions have been described as outlets for conceptual, theory-driven artists. Only one issue of the journal, Photographic Effect Journal, volume 1, was published, in 1976.

- Room 801, a gallery run by Daido Moriyama on Miyamasuzaka Street in Shibuya. Opened in June 1987, it was renamed Foto Daido in July 1988 and closed in March 1992.

- Gallery Kaido, an independent gallery near Nishi-Shinjuku Station run by Koji Onaka and Susumu Fujita. This gallery was active from April 1988 to October 1992.

- Place M, an independent gallery run by Masato Seto and Michio Yamauchi. It opened in December 1987, and Hiroyasu Nakai and Daido Moriyama joined the gallery in December 1994. Located in Yotsuya.

- Hokuten, a gallery run by Hiroyasu Nakai in his hometown of Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture, opened in March 1988.

- Independently published journal by Daido Moriyama. The first issue appeared in July 1972; it was discontinued after the fifth issue.

- Provoke was founded in 1968. It was initially run by a group that consisted of Koji Taki, Yutaka Takanashi, Takahiko Okada, and Takuma Nakahira; Daido Moriyama joined with the second issue. Provoke’s full title was Provoke: Provocative Materials for Thought. Discontinued in 1970.

- Referring to Kaiten (Revolve), a photo journal published by Hiroomi Sahara and Mie Morimoto. The first issue appeared in October 1995.