In the late 1960s, as demonstrators marched the streets of Tokyo in mass protest of the renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, two generations of photographers called for a public reckoning with the medium’s wartime responsibility. Collectively they invoked their colleague Yoshio Watanabe’s question, “What should a photographer be?”[1]

The resulting exhibition, Shashin 100 nen—Nihonjin ni yoru shashin hyogen no rekishiten (A Century of Japanese Photography), held in 1968 at the Seibu department store in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, was one of the most important photography shows of the twentieth century.[2] Analyzing one hundred years of work by Japanese photographers, it was the first presentation to reflect on their contributions to Japanese fascism during World War II. The accompanying book, when published in English in 1980, became the first major volume to introduce an international audience to Japanese contributions to the medium. The exhibition itself can be credited with bringing forward a new type of aesthetic: after looking through tens of thousands of pictures in their roles as curators of the exhibition, Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki founded the photography collective Provoke, whose are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) style continues to influence photographers around the world.[3]

The First Centralized Collection of Japanese Photographs

A Century of Japanese Photography displayed the results of the first archiving project to gather photographs and negatives from regional libraries, prominent families, and collectors located from the northern tip of Japan to its southernmost islands. The curators estimated that they collected more than one hundred thousand original prints and around thirty-five thousand reproductions in this unprecedented effort to evaluate existing public and private holdings of historic Japanese photographs.[4] The sheer volume of pictures gathered spurred the movement to build Japan’s first central photography museum and permanent archive of photographic materials, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.[5]

The exhibition was planned, curated, and executed by photographers hailing from a wide range of specializations, establishing them as archivists and theorists of work by their predecessors and contemporaries. The curatorial team was led by Shomei Tomatsu and included Nakahira, Taki, Hisae Imai, Masatoshi Naito, and Seiryu Inoue, among others, many of whom were affiliated with the Japan Professional Photographers Society (JPS).[6] The exhibition positioned the younger artists against their teachers in the first instance of public criticism of the work of the Japanese wartime generation, including photographers such as Ken Domon, Ihei Kimura, and Hiroshi Hamaya.[7]

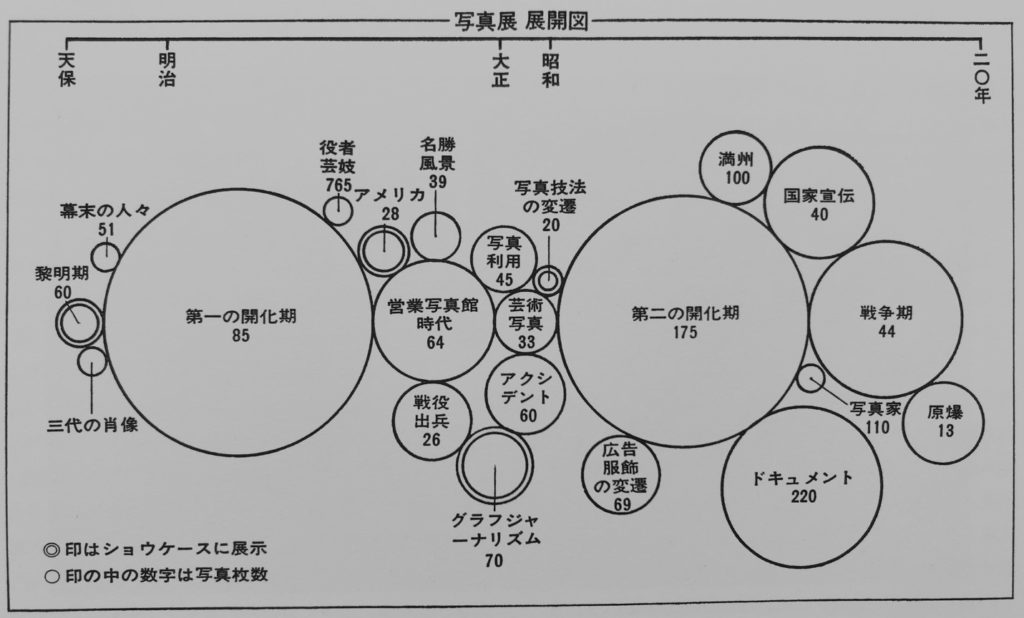

Preparation for the exhibition unfolded in two stages.[8] First, in the autumn of 1967, the curators gathered prints and negatives from local libraries and historical associations throughout Japan. These materials were sent back to the curatorial team’s office in Ginza, Tokyo, where they also stored thousands of books borrowed from the FujiFilm and Iwanami Shoten photography libraries for reference. Second, under Tomatsu’s direction, the team selected 1,640 pictures from the larger set, grouping the images into sections by their shashin hyogen (photographic style) (see figure 1). They met over a two-day period in April 1968 at an inn in Tsukiji, Tokyo, to organize the groupings, which included “Period of the First Enlightenment,” highlighting photography of the 1860s and 1880s; “Commercial Photography Studios,” focused on studios that were active from the 1870s to the 1920s; “Art Photography”; “Accidents”; “Changes in Fashion Advertising”; “National Propaganda”; “Manchuria,” featuring photographs of Japanese colonization of Manchuria; “Period of War”; and others. Each section established its own common visual vocabulary that centered on what Taki described as “the social consciousness [of the photographer] from the Meiji period to World War II.”[9]

Wartime Responsibility and Photographs as Reflections of the Real

The largest section, “The Document,” comprised anonymous pictures selected from magazine and newspaper archives, suggesting a new way of thinking about the connections between photographers and the scenes they sought to capture (see figure 2).[10] By filling the gallery with works by unknown authors that depicted specific historical events and places, the curators emphasized the importance of the content of the image. In contrast, the national propaganda works by well-known photographers such as Domon exemplified the use of the medium to create fictions in support of the war effort. Thus, the “National Propaganda” section with pictures pulled from mass-produced photography magazines such as Asahi Graph and Nippon demonstrated ways Japanese photographers had stopped trying to portray the real circumstances of life, instead presenting idealized fantasies to advertise the wartime Japanese imperial project (see figure 3). In the critic Tomomi Ito’s words, these were “photographs . . . taken from a position of great indifference to history.”[11]

Reflecting on the exhibition later, Tomatsu and many of the other curators concluded that the pictures on display were evidence of the collective failure of Japanese photographers to make images that analyzed historical events critically. Immediately following Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II, Japanese photographers—unlike Japanese painters and writers—did not engage in public self-criticism for colluding with the state and supporting the war effort.[12] In fact, those who had been the most active in producing propagandistic imagery, such as Domon and the photographer-editor Yonosuke Natori, continued in the postwar period to act as the gatekeepers for the photography world.[13] It was against these antecedents that Tomatsu, Nakahira, and Taki pushed back: in their view, these figures had used the visual techniques of the documentary photograph to present state lies to the Japanese public, calling the entire premise of the “document” into question.

For this reason, Taki and Nakahira became deeply invested in the meaning of the “document” and believed that challenging the very idea that photography could represent reality might set their work apart from that of the wartime generation. In their view, images of the colonial development of Japan’s northernmost island in the 1870s and 1880s by Kenzo Tamoto as well as pictures of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki by the military photographer Yosuke Yamahata were the only true examples of photographic documentation in the exhibition.[14] Taki and Nakahira argued that in their historical contexts, both photographers had found ways to be so fully present in the making of their pictures that they connected directly with their subjects.[15] In the months following the exhibition, Nakahira and Taki were joined by Yutaka Takanashi, Takahiko Okada, and later Daido Moriyama in an effort to come up with a completely new system of representation, one that was theoretically informed and positioned to be a catalyst for social change. Though the collective, Provoke, was short-lived, the are-bure-boke style that characterized their work left its mark on the Japanese photography world, offering new techniques that prioritized accidental, mechanical qualities driven by the camera and the desire to obliterate the photographer.

Building on the slim catalogue that had accompanied A Century of Japanese Photography, Tomatsu, Taki, and Naito worked with the JPS to write A History of Japanese Photography 1840–1945. At the time of its publication, in 1971, it was the most comprehensive history of Japanese photography written to date. Alongside 696 photographs that had been gathered for the exhibition, the book’s essays elaborate upon the original presentation’s critical premise. In 1980, Random House published an English translation of the volume with texts by historian John W. Dower, who would later be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his research on postwar Japan in Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999). Dower has noted that in his introduction to the book he “wanted to make the point that it wasn’t just superb ‘photography’ that we encountered here, but beyond this a brilliant window on the incredibly diversified and complex social and cultural dynamics of modern Japan.”[16]

Thus what began as a movement to preserve the legacy of Japanese photographers turned into a public reckoning with their role during World War II and its aftermath. Precisely because they were looking at this history from a nationwide perspective, comparing the work across time and space as never before, photographers of the postwar generation developed a critique of the function of the photographer and established a theoretically informed method that challenged the boundaries of photographic representation itself. These negotiations both inspired a new movement within the medium and created the framework through which Japanese photography was first introduced to a global audience.

Notes

- Yoshio Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen’ Nihonjin ni yoru shashin hyogen no rekishiten ni tsuite” (On “A Century of Japanese Photography”: A Historical Exhibition on Photographic Expression by the Japanese), Tokushugo shashin no hi koenkai (Special Edition Photography Day Lecture), Photographic Society of Japan Bulletin 7/8 (1968): 8. For more on the Japanese protests of the 1960s, see William Marotti, “Japan 1968: The Performance of Violence and the Theater of Protest,” American Historical Review 114, no. 1 (February 2009): 97–135.

- Though the Japanese title’s translation is closer to A Century of Photography: A Historical Exhibition of Photographic Expression by the Japanese, scholars have frequently simplified it to A Century of Japanese Photography, which I retain here.

- Tomomi Ito, Ichiro Murakami, Hiroshi Hamaya, Shomei Tomatsu, Koji Taki, Masatoshi Naito, Keiichi Kimura, Keisuke Kumakiri, and Norihiko Matsumoto, “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete” (The End of the “A Century of Japanese Photography” Exhibition), Nihon shashinka kyokai kaiho (Japan Professional Photographers Society Newsletter), no. 19 (1968): 10.

- Accounts of the number of photographs gathered vary. Watanabe, then president of the Japan Professional Photographers Society, claimed it was one hundred thousand, though Shomei Tomatsu later cited five hundred thousand. Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen,’” 8; Shomei Tomatsu, Masatoshi Naito, Koji Taki, Hisae Imai, and Hirano Hisashi, “Shashin hyogen no rekishi wo kataru: Nihon shashinka kyokai shashin 100 nen ten ni tsuite” (Narrating a History of Photographic Expression: On the Japan Professional Photographers Society “A Century of Japanese Photography” Exhibition), Asahi Camera (June 1968): 222–28. See also Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 24.

- The museum opened in 1990. Its English name was changed to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (TOP Museum) in 2016.

- The Japan Professional Photographers Society (JPS) was established in 1950 to support the legal rights of commercial photographers and photojournalists. The Photographic Society of Japan (PSJ) was established in 1952 to promote Japanese photography and the use of photography as a means of connection between Japan and other countries. Most postwar photography exhibitions in Japan were produced by photography organizations such as the JPS and PSJ, camera clubs, and camera corporations at galleries and department stores. Though the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, held six photography exhibitions between 1953 and 1974, it held none between 1974 and 1994. See Julia Thomas, “Raw Photographs and Cooked History: Photography’s Ambiguous Place in the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo,” East Asian History: The Continuation of “Papers on Far Eastern History,” no. 12 (December 1996): 125–26.

- Imai was the sole woman involved. The exhibition was sponsored by the Nihon Shashinki Kogyokai (the Japan Camera Industry Association, JCIA) and the Shashin Kanko Zairyo Kogyokai (the Photo-Sensitized Materials Manufacturer’s Association). See Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen,’” 8.

- For a detailed description of the exhibition’s planning, see Seiichi Tsuchiya, “Shashinshi 68 nen—‘shashin 100 nen’ saiko” (The History of Japanese Photography in 1968—Reconsidering “A Century of Japanese Photography”), Photographers’ Gallery Press, no. 8 (April 2009): 242–52. For an English translation of the abridged version, see Seiichi Tsuchiya, “The Whereabouts of the ‘Record’ Discovered—Reflections on A Century of Photography,” in Nihon shashin no 1968: 1966–1974 futtosuru shashin no mure (1968—Japanese Photography: Photographs That Stirred Up Debate, 1966–1974), ed. Ryuichi Kaneko and Hiroko Tasaka (Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2013), xiii–xxii.

- Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et. al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 24.

- The argument could be made that Nakahira drew on the “The Document” section display strategies for his photographic installation Circulation: Date, Place, Events at the 1971 Paris Biennale. See Franz Prichard, “On For a Language to Come, Circulation and Overflow: Takuma Nakahira and the Horizons of Radical Media Criticism in the Early 1970s,” in For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979, ed. Yasufumi Nakamori and Allison Pappas, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2015), 84–89.

- Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 22.

- On debates over war responsibility in postwar literary circles, see J. Victor Koschmann, “The Debate on Subjectivity in Postwar Japan: Foundations of Modernism as a Political Critique,” Pacific Affairs 54, no. 4 (Winter 1981–82): 609–31. On postwar photography, see Justin Jesty, “The Realism Debate and the Politics of Modern Art in Early Postwar Japan,” Japan Forum 26, no. 4 (September 2014): 508–29.

- In the 1950s Domon made a name for himself as the father of Japanese realism, though he had been using a similar photojournalistic style to shoot propaganda photographs for Nippon and Shashin Shuho, state-sponsored periodicals that glorified Japanese imperialism. For more on Domon’s postwar articulations of his photographic theory, see Julia Adeney Thomas, “Power Made Visible: Photography and Postwar Japan’s Elusive Reality,” Journal of Asian Studies 67, no. 2 (May 2008): 365–94.

- For an insightful critique of Nakahira and Taki’s decontextualized adoration of Kenzo Tamoto, see Gyewon Kim, “Reframing ‘Hokkaido Photography’: Style, Politics, and Documentary Photography in 1960s Japan,” History of Photography 39, no. 4 (December 2015): 348–65.

- See Philip Charrier, “Taki Koji, Provoke, and the Structuralist Turn in Japanese Image Theory, 1967–70,” History of Photography 41, no. 1 (April 2017): 25–43.

- Interview with the author, November 20, 2018.