Ownership History

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase through a gift of Phyllis Wattis, 1998

Exhibition History

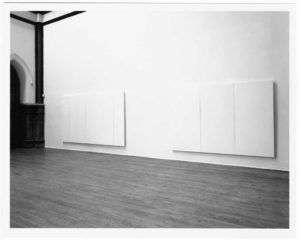

White Paintings 1951, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, October 12–27, 1968.

White Paintings (1951), Ace Gallery, Venice, California, April 10–May 15, 1973. Traveled to: Ace Gallery, Vancouver, Canada, June 1–June 16, 1973.

Robert Rauschenberg, National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., October 30, 1976–January 2, 1977. Traveled to: Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 25–May 17, 1977; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 24–August 21, 1977; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, September 25–October 30, 1977; Art Institute of Chicago, December 3, 1977–January 15, 1978.

Rauschenberg: Werke 1950–1980, Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin, March 23–May 4, 1980. Traveled to: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany, June 6–July 13, 1980; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, September 20–November 25, 1980; Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt, Germany, December 4, 1980–January 18, 1981; Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, February 4–April 5, 1981; Tate Gallery, London (as Robert Rauschenberg), April 29–June 14, 1981.

Rauschenberg: The White and Black Paintings 1949–1952, Larry Gagosian Gallery, New York, April 18–May 31, 1986.

White, BlumHelman Gallery, New York, January 7–31, 1987.

Art by Chance: Fortuitous Impressions, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, July 22–September 3, 1989.

Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., June 15–August 11, 1991. Traveled to: The Menil Collection, Houston, September 27, 1991–January 5, 1992; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, February 8–April 19, 1992; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, May 14–August 16, 1992; Guggenheim Museum SoHo, New York, October 24, 1992–January 24, 1993.

Il suono rapido delle cose: Cage & Company, 45th Biennale di Venezia, Palazzo Grazzi, Venice, Italy, June 9–October 10, 1993.

The Second Hiroshima Art Prize: Robert Rauschenberg, Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, November 3, 1993–January 16, 1994.

Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, September 19, 1997–January 7, 1998. Traveled to: The Menil Collection, Houston, February 13–May 17, 1998; Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany, June 27–October 11, 1998; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, November 21, 1998–March 7, 1999.

Robert Rauschenberg, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, May 7–September 7, 1999.

Points of Departure II: Connecting with Contemporary Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, November 17, 2001–June 9, 2002.

Robert Rauschenberg at SFMOMA, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 27–September 8, 2002.

Treasures of Modern Art: The Legacy of Phyllis Wattis at SFMOMA, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, January 30–June 24, 2003.

The Art of Participation: 1950 to Now, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, November 8, 2008–February 8, 2009.

The Anarchy of Silence: John Cage and Experimental Art, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, October 23, 2009–January 10, 2010. Did not travel to remaining venues.

75 Years of Looking Forward: The Anniversary Show, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, December 19, 2009–January 16, 2011 (on view July 1, 2010–January 16, 2011).

A House Full of Music, Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt, Germany, May 13–September 9, 2012.

In addition to appearing in the special exhibitions listed above, White Painting [three panel] was shown in SFMOMA’s galleries in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2016 as part of a series of rotating presentations of the permanent collection.

This listing has been updated since the launch of the Rauschenberg Research Project and is complete as of August 31, 2016.

Publication History

Donald Finkel, A Joyful Noise: Poems by Donald Finkel (New York: Atheneum, 1966), 62–69.

Robert Pincus-Witten, “New York: Robert Rauschenberg, Castelli Gallery,” Artforum 7, no. 4 (December 1968): 56.

Richard Kostelanetz, Master Minds: Portraits of Contemporary American Artists and Intellectuals (New York: Macmillan, 1969), 261.

Melinda Terbell, “Rauschenberg Newly Seen,” Artweek, May 5, 1973, 1, 16 (ill.).

Walter Hopps, ed., Robert Rauschenberg (Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1976), 2 (ill.), 66 (ill.).

“Rauschenberg Exhibit Summons Artistic Questions,” The Ark (Tiburon, CA), July 20, 1977.

Robert Rauschenberg: Retrospective, directed by Michael Blackwood (New York: Michael Blackwood Productions, 1979), VHS, 45 min.

Dieter Ruckhaberle, ed., Rauschenberg: Werke 1950–1980, trans. Janni Müller-Hauck and Vincent Thomas (Berlin: Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin, 1980), 259 (ill.), 382.

Robert Rauschenberg (London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1981), n.p.

Leslie Geddes-Brown, “The Artist Who Turns a Hanging into a Happening,” Sunday Times (London), May 3, 1981.

Antonia Phillips, “Cleaning Up,” Times Literary Supplement (London), May 22, 1981, 572.

Rauschenberg: The White and Black Paintings 1949–1952 (New York: Larry Gagosian Gallery, 1986), n.p. (ill.).

Roni Feinstein, “The Early Work of Robert Rauschenberg: The White Paintings, the Black Paintings, and the Elemental Sculptures,” Arts Magazine 61, no. 1 (September 1986): 28, 34 (ill.).

George McKenna, Art by Chance: Fortuitous Impressions (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1989), 51–52.

Roni Feinstein, “Random Order: The First Fifteen Years of Robert Rauschenberg’s Art, 1949–1964” (PhD diss., New York University, 1990), iii, 87.

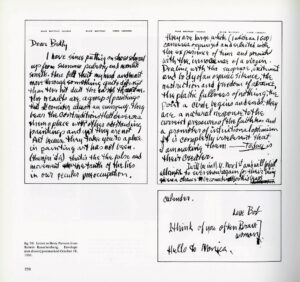

Walter Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s (Houston: Menil Foundation and Houston Fine Art Press, 1991), 62, 80, 83 (ill.).

———, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s (Houston: Menil Foundation, 1991), 31. Produced for the Menil presentation only.

Seiji Oshima, Marjorie Welish, Takeshi Yoshizumi, et al., The Second Hiroshima Art Prize: Robert Rauschenberg (Hiroshima: Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, 1993), 53 (ill.), 173.

Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson, eds., Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 23, 31, 44, 57 (ill.), 227, 264, 311.

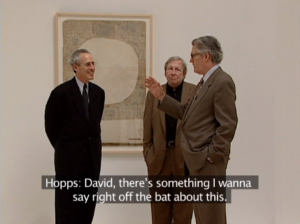

Robert Rauschenberg, video interview by David A. Ross, Walter Hopps, Gary Garrels, and Peter Samis, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, May 6, 1999. Unpublished transcript, SFMOMA Research Library and Archives, N 6537 .R27 A35 1999a, 13–20.

Kenneth Baker, “Rauschenberg Coup at SFMOMA: ‘Port of Entry’ a Major New Work,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 8, 1999.

Branden W. Joseph, “Blanc sur blanc: Robert Rauschenberg et John Cage,” Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, no. 71 (Spring 2000): 4–31.

———, “White on White,” Critical Inquiry 27, no. 1 (Autumn 2000): 90–119, 120 (ill.), 121.

“‘Points of Departure II’ at SFMOMA Explores Contemporary Art,” Antiques and the Arts, May 3, 2002.

Branden W. Joseph, Random Order: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-Garde (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 70 (ill.).

Paul Schimmel, ed., Robert Rauschenberg: Combines (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005), 260 (ill.).

Mark A. Cheetham, Abstract Art Against Autonomy: Infection, Resistance, and Cure since the ’60s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 47 (ill.).

James Rondeau and Douglas Druick, Jasper Johns: Gray (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2007), 38 (ill.).

Rudolf Frieling, Boris Groys, Robert Atkins, et al., The Art of Participation: 1950 to Now (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 82, 84 (ill.).

Bruno Marchand, ed., Robert Rauschenberg: Crítica e obra de 1949 a 1974 (Porto, Portugal: Fundação de Serralves, 2008), 44 (ill.).

The Anarchy of Silence: John Cage and Experimental Art (Barcelona: Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 2009), 179 (ill.), 293.

“SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: Peter Samis,” interview conducted by Jess Rigelhaupt, 2008, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2009, 8. Accessed June 23, 2013. https://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ROHO/projects/sfmoma/interviews.html.

“SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: David White,” interview conducted by Richard Cándida Smith, Sarah Roberts, Peter Samis, and Jill Sterrett, 2009, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2010, 30, 39, 40, 53, 56–57. Accessed June 23, 2013. www.bancroft.berkeley.edu/ROHO/projects/sfmoma/interviews.html

Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts, eds., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 146.

Carolyn Lanchner, Robert Rauschenberg (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 6, 8 (ill.).

Terri Cohn, “The Art of Participation: 1950 to Now,” College Art Association Reviews, February 18, 2009.

Kyle Gann, No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33“ (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 156.

Tom Folland, “Robert Rauschenberg’s Queer Modernism: The Early Combines and Decoration,” Art Bulletin 92 (December 1, 2010): 353 (ill.).

Ralf Beil and Peter Kraut, eds., A House Full of Music: Strategies in Music and Art (Darmstadt, Germany: Institut Mathildenhöhe, 2012), 33, 36, 45n60, 121 (ill.), 123.

Reggie Michael Rodrigue, “The Only Stair that Doesn’t Creak: Silence,” Oxford American, September 4, 2012, (ill.). Accessed June 30, 2013. https://www.oxfordamerican.org/articles/2012/sep/04/only-stair-doesnt-creak-silence/.

Jeffrey Saletnik, “John Cage and the Task of the Translator,” Art in Translation 4, no. 1 (March 2012): 79 (ill.).

Craig Dworkin, No Medium (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 118.

White Collar Crimes (New York: Acquavella Galleries, 2013), 11 (ill.).

Sidra Stich, Yves Klein (London: Hayward Gallery, 1994), 71 (ill.).

Valerie Hellstein, “The Cage-iness of Abstract Expressionism,” American Art 28, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 58 (ill.).

Christopher Knight, “Alas, mere ‘Shadows’ in MOCA’s Andy Warhol exhibit,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 2014.

Isabelle Malz, ed., The Problem of God (Düsseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2015), 20, 70–71 (ill.), 276, 313.

Craig Staff, Monochrome (London: I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd., 2015), 83.

This listing has been updated since the launch of the Rauschenberg Research Project and is complete as of August 31, 2016.