Artist

Eikoh Hosoe

Japanese

1933, Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture

2024

interviews

- see transcript

Eikoh Hosoe: Does photography reflect truth?

Photographer Eikoh Hosoe discusses his photobook Kamaitachi (1969) and its theatrical reflection of real life. He considers the avant-garde performances documented in the publication, their star, and how Kamaitachi responded to the realism of work by other photographers of the time.

Works in the Collection by Eikoh Hosoe

-

Eikoh Hosoe

Man and Woman #20

1960 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Ordeal by Roses #6

1961, printed ca. 1975 -

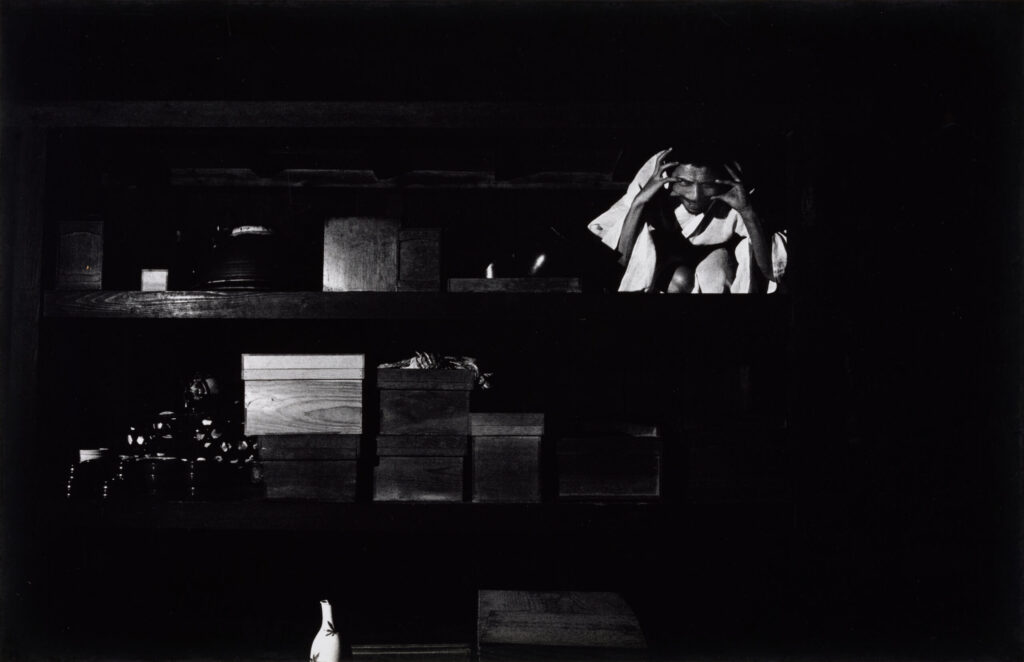

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #19

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #13

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #3

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #14

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #5

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #8

1965, printed 1971 -

Eikoh Hosoe

Kamaitachi #11

1965

Essays and Artist Talks

-

Exhibiting “The End of Modern Photography”: Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography and Fifteen Photographers Today

February 2022

The exhibitions Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography (July 15–August 21, 1966) and Fifteen Photographers Today (July 26–September 8, 1974), held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, gathered recent works by artists who played indispensable roles in the development of Japanese photography after World War II.[1] They featured key representatives of the first generation of postwar photographers such as Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, and Shomei Tomatsu—all members of the VIVO group, which sought to renew photographic expression—as well as figures associated with the influential journal Provoke such as Daido Moriyama, Takuma Nakahira, and Yutaka Takanashi. The earliest work, shown in Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography, dated to 1962, while Fifteen Photographers Today included ongoing series published in journals through (and beyond) the year of the exhibition itself. The two presentations together thus highlighted the major trends of nearly fifteen years of Japanese photography—an era that is now regarded as one the most exciting periods for the medium in postwar Japan. In order to understand the significance of these exhibitions, one must first consider the backdrop. The National Museum of Modern Art, founded in 1952 in the Kyobashi area of Tokyo, mounted The Exhibition of Contemporary Photography—Japan and America one year after its establishment. As indicated by its title, the exhibition united some of the most significant Japanese postwar photography with American works, selected from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.[2] In the thirteen years between that presentation and Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography, the museum held six more photography shows.[3] Many focused on Japanese photography specifically, and most centered on work from the postwar era. All of them prioritized the introduction of contemporary trends. In those days, the National Museum of Modern Art did not have a curator of photography. Instead, up through the time of Fifteen Photographers Today, it nominated curatorial committees of external specialists to determine the content of its photography exhibitions. The committee members were Japan’s most renowned photography critics and editors of leading photography journals—figures who, month by month, browsed the pages of publications dedicated to the art form and wrote critical essays and commentaries, both closely following and shaping current trends. Due to the curators’ broad insights into the field, their exhibitions provided well-balanced overviews of the medium during this period; one might call them straightforward expressions of the self-image of the Japanese photography scene, analyzing contemporary movements and highlighting their most representative works rather than addressing particular topics. Prime examples were the three Contemporary Photographs exhibitions of 1960, 1961, and 1963. Each of these nearly annual presentations featured pictures that had been published in magazines or exhibited the preceding year, offering a cross section of the most recent and outstanding developments in the field.[4]Three years after the cancellation of the Contemporary Photographs shows, the museum mounted Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography, this time using a different curatorial framework. According to a text in the exhibition catalogue (fig. 1) by Shigene Kanamaru, a member of the selection committee, the participating photographers could be divided into two groups: those who started working from ideas or concepts, reflecting a “subjective” approach, and those who were more concerned with understanding the people, places, and things they depicted, reflecting an “objective” approach.[5] Kanamaru adapted this terminology from the notion of “subjective photography” that had gained traction in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[6] Thus, whereas the Contemporary Photographs exhibitions aimed to present comprehensive selections of the best work in all genres from a given year—from the purely artistic to photojournalism, advertisements, and scientific photography—Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography moved in a more narrowly defined direction, considering the trends of the past several years but highlighting only those deemed most deserving of broader attention.[7] The organizers of Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography, and later Fifteen Photographers Today, also deliberately focused on a new generation. While the Contemporary Photographs exhibitions showcased pictures by photographers of a considerable age range, all of the participants in Ten Artists of Contemporary Japanese Photography began their careers after the war. With Yoshinobu Nakamura the oldest, at forty-one, and Kishin Shinoyama the youngest, at twenty-five, the group was quite young overall. This narrow age range would persist in Fifteen Photographers Today, where Masahisa Fukase was the oldest artist with work in the show, at forty, and Shigeru Tamura was the most junior, at twenty-seven. While all of the photographers had already received some degree of acclaim, they were still considered relatively young.

related exhibition

related exhibition

The Provoke Era

Postwar Japanese Photography

September 12–December 20, 2009

The tumultuous period following World War II proved fertile ground for a generation of Japanese photographers who responded to societal upheaval by creating a new visual language dubbed “Are, Bure, Boke” — rough, blurred, and out of focus. Named for the magazine Provoke, which sought to break the rules of traditional photography, this exhibition traces how Japanese photographers responded to their country’s shifting social and political atmosphere. Though American audiences may be less familiar with photographers like Masahisa Fukase, Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama, and Shomei Tomatsu, SFMOMA has been actively acquiring the work of these internationally recognized artists since the 1970s. The works in the show all come from the SFMOMA collection, considered one of the preeminent holdings of Japanese photography in the United States.

This exhibition is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and is generously supported by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.

Go to Exhibition

Please note that artwork locations are subject to change, and not all works are on view at all times.

Only a portion of SFMOMA's collection is currently online, and the information presented here is subject to revision. Please contact us at collections@sfmoma.org to verify collection holdings and artwork information. If you are interested in receiving a high resolution image of an artwork for educational, scholarly, or publication purposes, please contact us at copyright@sfmoma.org.

This resource is for educational use and its contents may not be reproduced without permission. Please review our Terms of Use for more information.